The Uprising of 1 Prairial Year III (20 May 1795) was the last major popular insurrection during the French Revolution (1789-1799). It was the final time that the sans-culottes played an important role in French politics until the revolutions of the 19th century, and it dashed any hopes that the Jacobins would regain power after the fall of Maximilien Robespierre.

The Prairial Uprising was sparked by the conservative policies of the Thermidorian Reaction. The Thermidorians, who had overthrown Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794) and ended the Reign of Terror, had been intent on erasing the extremist Jacobin ideology from French politics. This included ending the Law of the General Maximum, which had placed a price cap on bread and other essential supplies, keeping them somewhat affordable. The removal of such regulations, coupled with a particularly brutal winter, led to mass starvation and worsened rates of poverty.

On 20 May 1795, or 1 Prairial Year III in the French Republican calendar, the sans-culottes of Paris rose against the Thermidorian Convention, demanding bread and the Constitution of 1793. Ultimately, their revolt petered out, and the ringleaders were brutally punished by the Thermidorians. The failure of the insurrection is significant in showing mounting revolutionary fatigue, as similar insurrections had previously been major turning points in the Revolution. After crushing the uprising, the Thermidorians wrote their own Constitution of Year III, which led to the establishment of the French Directory.

Power of the People

The peoples' insurrections, or revolutionary journées ('days') as they were often called, were a proud tradition in the history of the French Revolution. In fact, it could be argued that had it not been for these journées, there would have been no Revolution at all. It was the people who had risen up on 14 July 1789 in the Storming of the Bastille, which had helped solidify the power of the National Constituent Assembly and had given the Revolution its mandate. It was the people, not legislators, who had forced King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) to move from his absolutist fortress of Versailles to Paris during the Women's March on Versailles, and it had been an insurrection of the people that had ended the monarchy in the Storming of the Tuileries Palace.

By the summer of 1793, the power of the revolutionary lower classes, the sans-culottes, had grown to a point where they could raise up or overthrow regimes almost at will. In the insurrection of 2 June 1793, the people had caused the fall of the Girondins, a faction in the National Convention whose moderate policies were destroying the Revolution in the eyes of the sans-culottes. In helping to destroy the Girondins, the sans-culottes brought the extremist Jacobin faction known as the Mountain to power. Although these insurrections often excluded the rest of the nation from having a say in national politics (leading to the outbreak of the federalist revolts), for the people of Paris at least, these revolutionary insurrections represented democracy in its bloodiest, most chaotic form.

Yet as the Revolution continued with no end in sight, the power of these popular insurrections began to wane. Fearful of being overthrown in the way the king and the Girondins had been, Robespierre and the dictatorial Committee of Public Safety had Paris' sections infiltrated by spies and agents, intent on nipping any future uprising in the bud. This decision proved prudent in March 1794, when a planned insurrection in support of the ultra-radical Hébertist faction was thwarted before it had even begun; Robespierre had 19 Hébertist leaders rounded up and executed.

Of course, the Mountain's declawing of the sans-culottes would backfire. When Robespierre needed an insurrection to rise up and save him from the Thermidorian coup in July 1794, the sans-culottes had become so unorganized by Robespierre's own Reign of Terror that they could not mobilize in time. Robespierre was executed and his regime toppled before the radical elements of Paris' sections could even attempt to come to the rescue.

During the ensuing Thermidorian Convention of 1794-95, successful popular insurrections were fading into memory. The people of Paris, who had once made kings and bourgeois legislators tremble in their silk stockings, had been relegated back to what they had been in the days of the old regime: starving, impoverished workers, nothing more. Whether they could take the Revolution away from the bourgeois Thermidorians and back into their own hands remained to be seen.

A Brutal Winter

The winter of 1794-95 was one of the worst that France had experienced in the entire 18th century. Rivers froze solid, while the already scarce supply of firewood and coal became rarer still. The meagre harvest of 1794 put a strain on the population, as the French armies fighting in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) had first claim on the available product. While the government had imported grain from abroad, the supplies could not be transported across the country, since roads and waterways were blocked by the winter chill.

Matters were worsened by the free market policies of the Thermidorian Convention. As part of their efforts to undo the Jacobins' radical policies, the Thermidorians repealed the Law of the General Maximum, which had kept a price cap on bread and other essential supplies. Their rationale was that such a law hurt farmers and other producers, who could no longer set their own prices, and that such a policy worsened inflation. They also believed that a free market was the best way to revitalize France's withering economy. Unfortunately, they implemented this policy just before the harsh winter set in, meaning that at a time the people needed bread, fuel, and other supplies the most, prices skyrocketed. The Thermidorians attempted to remedy the situation by issuing fresh batches of Revolutionary France's paper currency, the assignat, into circulation, but this only increased inflation.

Subsequently, the streets of Paris were littered with frostbitten, malnourished people. Death rates in the city spiked as people froze to death in their own homes or starved. Suicides also dramatically increased, as many sought to avoid those horrible fates. Such a miserable situation made many think back nostalgically to Jacobin rule and the Reign of Terror; as violent as those days had been, bread had at least been more affordable. Naturally, many blamed the Thermidorians and unrest in the city grew.

The Call of the Tocsin

The deadly winter chill did not subside until early April 1795. By then, French armies all over Europe were winning victories against the Republic's enemies, to the point that some members of the Coalition against France had begun to sue for peace. Far from placating the sans-culottes of Paris, this news only embittered them; how could a government that was powerful enough to conquer Europe fail to procure bread for its people?

As if to emphasize this point, the end of winter did not equate to more bread in the bellies of Parisians. There were no untapped reserves of bread anywhere in the country, and squadrons of British warships made it difficult to import any more from overseas. In Paris, daily rations of bread became less and less nourishing. On 22 April, one diarist wrote: "All Paris has been reduced today to a quarter pound of bread each. Never has Paris found itself in such distress" (Doyle, 284). By 1 May, this had decreased to only two ounces of bread per Parisian. Women began to scold their men for lacking the courage to storm the halls of the National Convention and demand bread, while royalists began to smugly remind folks that things had not been this bad when kings had ruled France. It seemed as if the next journée was long overdue.

On 19 May, the signal was given with the anonymous publication of a pamphlet entitled People's Insurrection to Obtain Bread and Recover Our Rights. The pamphlet gave the insurrection concrete goals, namely bread and the Constitution of 1793. This second aspect alluded to the fact that France had been without a constitution since 1792. One did exist; the so-called Constitution of 1793 had been written by the Jacobins and would have been more radically democratic than any contemporary constitution, but the constitution was never implemented, having been shelved by the National Convention in order to give the Committee of Public Safety the executive powers needed to win the French Revolutionary Wars. Now, almost two years later, the Committee of Public Safety was gone, the Terror was over, and the wars appeared to be winding down. Still, the Thermidorians were showing no signs of planning to adopt the constitution, to the chagrin of the sans-culottes.

At 7 in the morning on 20 May, the ringing of the city tocsin echoed throughout Paris, a call to arms as old as the Revolution itself. At the call of the tocsin, the city's workers left their workshops and factories, taking to the streets in a great procession toward the Tuileries Palace, where the National Convention met. There were food riots as they went, and the marchers gestured for people working in shops or riding past in carriages to come and join them. In a scene harkening back to the glory days of the people's insurrections of 1789, the marchers pinned tricolor ribbons on their hats and bonnets and carried slogans echoing their demands for bread and the constitution.

Uprising of 1 Prairial

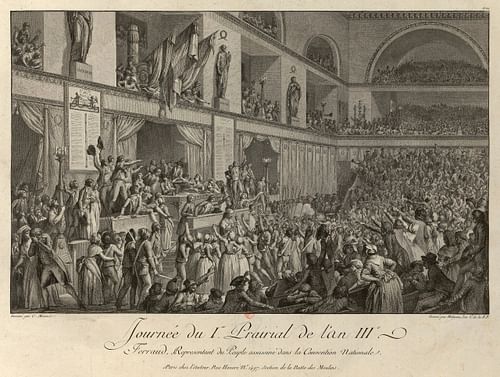

The date was 1 Prairial Year III in the new Republican calendar when the hungry citizens of Paris descended on the Convention. They were joined by detachments of the National Guard, mostly from the radical districts of Saint-Antoine and Saint-Marcel. The first insurrectionists to arrive at the Tuileries were met with the clubs and whips of the muscadins, the foppishly dressed thugs who made it their business to beat up Jacobins and sans-culottes. This had the same effect as poking a hornet's nest, and by early afternoon thousands of insurrectionists had surrounded the Convention. The aforementioned diarist noted that "everyone was in a massacring mood" (Doyle, 295).

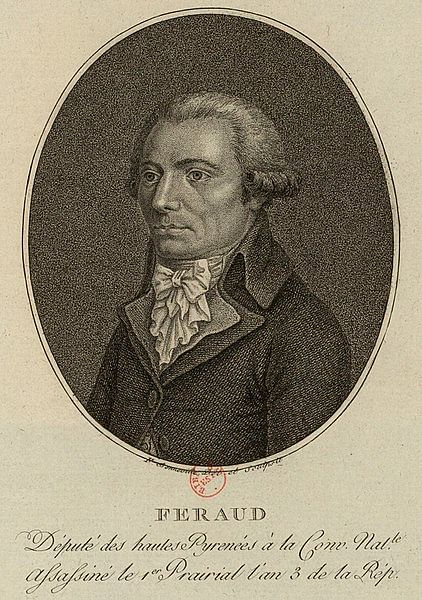

Eventually, the crowd began to push into the palace itself. They were greeted by a Convention deputy, Jean-Bertrand Féraud, who urged them to go home. In response, someone shot Féraud dead, and members of the crowd went to work sawing off his head and fixing it atop a pike. The mob then burst into the room where the Convention was sitting. As the insurrectionists waved their grisly trophy in the face of the Convention president, their list of demands grew to include the release of imprisoned Jacobin patriots who had been arrested after Robespierre's fall. They also called for the arrests of royalist émigrés and of the Thermidorians who had persecuted the Jacobins with such vigor. These demands were echoed by some deputies of the National Convention itself; 11 deputies of the Mountain (now derisively referred to as the 'Crest' since there were so few of them left) sided with the sans-culottes. If there was ever a chance for the Mountain to regain power, this was it.

Yet these 11 deputies sealed their fates with their own words. Earlier in the day, news of the gathering insurrection had caused the deployment of soldiers loyal to the Convention. By now, these soldiers had amassed outside of the Convention, waiting on the order to advance. It was some time before the order was finally given; some have since speculated that this delay was intentional, to give the deputies of the Mountain sufficient time to incriminate themselves. Once the order was given, however, the soldiers swiftly executed it. By midnight, the Tuileries Palace had been cleared of all insurrectionists; while there had been some violence, the soldiers dispersed them without firing a shot.

Standoff

Of course, the insurrection would not be quelled so easily. In the early hours of 21 May, sans-culotte leaders made appeals to the disgruntled Saint-Antoine district, which responded by sending more National Guardsmen to reinforce the insurrection, equipped with cannons. With these reinforcements, the insurrectionists returned to the Tuileries; by midafternoon, their numbers had swelled to 20,000. They faced off against 40,000 soldiers and other Convention loyalists who were defending the Tuileries. Not all of these defenders were dependable, however; throughout the day, scores of soldiers deserted their posts and snuck over to join the insurrection. Should it come to battle, the defenders were just as likely to flee or join the enemy as they were to stand and fight.

For this reason, the Convention was hesitant to start a battle. Similarly, the insurrectionists were just as eager to avoid a fight, knowing that they were heavily outnumbered and outgunned. As a result, each side stood its ground, neither willing to make the first move. After this staring contest had gone on for a while, the National Convention appeared to extend an olive branch and announced that it would receive a petition from the sans-culottes. Relieved, the insurrectionists asked once more for bread and the Constitution of 1793. Soothed by promises from the deputies to consider these issues, the ire of the insurrectionists faded. By evening, most of them had gone home.

In that instant, the sans-culottes had blinked; the momentum that they had given up by going home would never be recovered. Almost as soon as the insurrectionists ceased to pose an immediate threat, the Convention burned all records of the votes that had promised the sans-culottes bread, claiming that such a decision had been made under duress and therefore was not binding. The 11 Mountain deputies were arrested, accused not only of taking advantage of the insurrection but also of planning it (the latter claim was unfounded). With the insurrection ended and the threat from the few remaining Mountaineers neutralized, the Thermidorian Convention embarked on a path of retribution to ensure that it would never face a serious sans-culotte uprising again.

Retribution

On 22 May, the day after the insurrection dispersed, the Convention ordered troops under the command of General Jacques-François Menou to besiege the disloyal Saint-Antoine district. The soldiers were joined by squads of muscadins, always happy to deliver a good thrashing to sans-culottes; the other Paris Sections, ordered to join their National Guards to Menou's soldiers in a display of loyalty, were more reluctant to participate in this purely punitive action.

The overenthusiastic muscadins charged the Saint-Antoine barricades before the regulars had mobilized and were repulsed. Later that day, workers from Saint-Antoine attacked a group of police who were arresting one of the assassins of Féraud, freeing the man. But, as had been the case the day before, no one was eager to resort to a full-fledged battle, and General Menou announced that the Convention would be satisfied if Saint-Antoine agreed to hand over the men who had killed Féraud and disarm itself. If this occurred, there would be no more acts of retribution. Reluctantly, the section agreed. It surrendered and tore down its barricades. Féraud's killers were arrested and promptly guillotined.

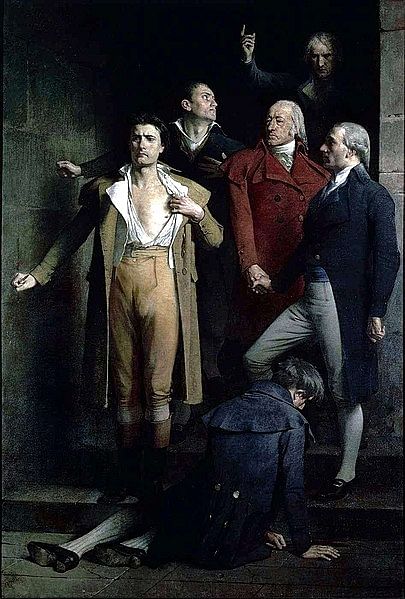

Again, the Convention failed to keep its promise; in the coming days, 3,000 people were arrested for their suspected participation in the insurrection. On 23 May, a special commission was set up to try 132 of the suspected ringleaders, including the 11 Mountain deputies. In the end, only 19 men were condemned to die; this included the killers of Féraud, the soldiers who had joined the insurrection, and 6 of the Mountaineers. In a final act of defiance, four of the condemned deputies attempted to kill themselves as they were being escorted from the courtroom, stabbing themselves with concealed knives. Three were successful; the fourth was guillotined along with the other two deputies. The 6 condemned Mountaineers became heroes in the Jacobin pantheon and were referred to as the "martyrs of Prairial".

With the end of the Prairial Uprising came the end of sans-culotte power in the French Revolution. A force that had once brought a kingdom to its knees was snuffed out on 21 May 1795, by the bourgeois legislators who had recently claimed to be their spokesmen. The Mountain, which had lacked any real power since the fall of Robespierre and the end of the Terror, continued to languish after its fall from grace, having missed its chance to retake control of the Revolution. As for the famous revolutionary journées, they were over; the revolt of 13 Vendémiaire (5 October 1795) would claim to carry on the legacy of popular insurrection, though this was a royalist uprising not in the same category as the republican journées, which would not return until the revolutions of 1830 and 1848.

One of the most important legacies of the failed insurrection was that it doomed the Constitution of 1793, which was now viewed as a rallying point for rebellion. The Thermidorians officially scrapped the Jacobin constitution, which they deemed unworkable in practice, and went to work crafting their own, more conservative Constitution of Year III (1795). Implemented on 22 August, this constitution led to the establishment of the French Directory and would remain in place until the Coup of 18 Brumaire brought the French Revolution to an end in November 1799.