The Predynastic Period in Ancient Egypt is the time before recorded history from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic Age and on to the rise of the First Dynasty and is generally recognized as spanning the era from c. 6000-3150 BCE (though physical evidence argues for a longer history). While there are no written records from this period, archaeological excavations throughout Egypt have uncovered artifacts which tell their own story of the development of culture in the Nile River Valley. The periods of the Predynastic Period are named for the regions/ancient city sites in which these artifacts were found and do not reflect the names of the cultures who actually lived in those areas.

The Predynastic Period was given its name in the early days of archaeological expeditions in Egypt before many of the most important finds were discovered and catalogued which has led some scholars to argue over when, precisely, the Predynastic Period begins and, more importantly, ends. These scholars suggest the adoption of another designation, 'Protodynastic Period', for that span of time closer to the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-2613 BCE) or 'Zero Dynasty'. These designations are not universally agreed upon and 'Predynastic Period' is the term most commonly accepted for the period prior to the first historical dynasties.

Manetho's History

In charting the history of ancient Egypt, scholars rely on archaeological evidence and ancient works such as the Egyptian dynastic chronology of Manetho, a scribe who wrote the Aegyptiaca, the History of Egypt, in the 3rd century BCE. The scholar Douglas J. Brewer describes the work: "Manetho's history was, in essence, a chronology of events arranged from oldest to most recent, according to the reign of a particular king" (8). Brewer continues on to describe the events which inspired Manetho to write his history:

The origin of the dynastic chronological system dates back to the time of Alexander the Great. After Alexander's death, his empire was divided among his generals, one of whom, Ptolemy, received the richest prize, Egypt. Under his son, Ptolemy II Philadelphus (c. 280 BC), an Egyptian priest named Manetho wrote a condensed history of his native land for the new Greek rulers. Manetho, a native of Sebennytus in the Delta, had been educated in the old scribal traditions. Although Egypt's priests were famous for handing out tidbits of information (often intentionally incorrect) to curious travellers, none had ever attempted to compile a complete history of Egypt, especially for foreigners (8).

Unfortunately, Manetho's original manuscript has been lost and the only record of his chronology is from the works of later historians such as Flavius Josephus (37-100 CE). This has led to some controversy over how accurate Manetho's chronology is but, even so, it is routinely consulted by scholars, archaeologists, and historians in charting the history of ancient Egypt. The following discussion of the Predynastic Period relies on archaeological finds over the past two hundred years and their interpretation by archaeologists and scholars but it should be noted that historical sequences did not seamlessly follow each other, like chapters in a book, as the dates given for these cultures suggest. Cultures overlapped and, according to some interpretations, 'different cultures' in the Predynastic Period can be seen as simply developments of a single culture.

Early Habitation

The earliest evidence of human habitation in the region is thought by some to go back as far as 700,000 years. The oldest evidence of structures discovered thus far were found in the region of Wadi Halfa, ancient Nubia, in modern-day Sudan. These communities were built by a hunter-gatherer society who constructed mobile homes of flat sandstone floors most likely covered by animal skins or brush and perhaps held up by wooden stakes. The actual structures vanished centuries ago, of course, but man-made depressions in the earth, with stone floors, remained. These depressions were discovered by the Polish archaeologist Waldemar Chmielewski (1929-2004 CE) in the 1980's CE and were designated 'tent rings' in that they provided an area to set up a shelter which could easily be taken down and moved, similar to what one would find at a modern campsite. These rings are dated to the Late Paleolithic Age of approximately the 40th millennium BCE.

Hunter-gatherer societies continued in the region throughout the periods now designated as those of the Aterian and Khormusan during which stone tools were manufactured with greater skill. The Halfan Culture then flourished c. 30,000 BCE in the region between Egypt and Nubia which gave way to the Qadan and Sebilian Cultures (c. 10,000 BCE) and the Harifan Culture from around the same time. All of these societies are characterized as hunter-gatherers who eventually became more sedentary and settled into more permanent communities centered around agriculture. Brewer writes:

One of the most intriguing mysteries of prehistoric Egypt is the transition from Paleolithic to Neolithic life, represented by the transformation from hunting and gathering to sedentary farming. We know very little about how and why this change occurred. Perhaps nowhere is this cultural transition more accessible than in the Fayyum depression (58).

The Fayyum depression (also known as the Faiyum Oasis) is a natural basin south-east of the Giza Plateau which gave rise to the culture known as Faiyum A (c. 9000-6000 BCE). These people inhabited the area around a large lake and relied on agriculture, hunting, and fishing for their living. Evidence of seasonal migration has been found but, for the most part, the area was continually inhabited. Among the earliest artworks discovered from this period are pieces of faience which appear to have already been an industry as early as 5500 BCE at Abydos.

Development of Culture in Lower Egypt

The people of Faiyum A built reed huts with underground cellars for storage of grains. Cattle, sheep, and goats were domesticated and baskets and pottery making developed. Centralized forms of tribal government began in this period with tribal chieftains assuming positions of power which may have been passed on to the next generation in a family or tribal unit. Communities grew from small tribes which traveled together to extended groups of different tribes living in one area continuously.

The Faiyum A Culture gave rise to the Merimde (c. 5000-4000 BCE), so-called because of the discovery of artifacts at the site of that name on the western edge of the Nile Delta. According to scholar Margaret Bunson, the reed huts of the Faiyum A period gave way to "pole-framed huts, with wind-breaks, and some used semi-subterranean residences, building the walls high enough to stand above ground. Small, the habitations were laid out in rows, possibly part of a circular pattern. Granaries were composed of clay jars or baskets, buried up to the neck in the ground" (75). These developments were improved upon by the El-Omari Culture (c. 4000 BCE) who built oval huts of greater sophistication with walls of plastered mud. They developed blade tools and woven mats for floors and walls and more sophisticated ceramics. The Ma'adi and the Tasian Cultures developed about the same time as the El-Omari characterized by further developments in architecture and technology. They continued the practice of ceramics without ornamentation begun in the El-Omari period and made use of grindstones. Their greatest advance seems to have been in the area of architecture as they had large buildings constructed in their community with underground chambers, stairs, and hearths. Prior to the Ma'adi Culture, the deceased were buried in or near people's homes for the most part but, around c.4,000 BCE, cemeteries became more widely used. Bunson notes that "three cemeteries were in use during this sequence, as at Wadi Digla, although the remains of some unborn children were found in the settlement" (75). Improvements in storage jars and weaponry is also characteristic of this period.

Cultures of Upper Egypt

All of these cultures grew and flourished in the region known as Lower Egypt (northern Egypt, closest to the Mediterranean Sea) while civilization in Upper Egypt developed later. The Badarian culture (c. 4500-4000 BCE) seems to have been an outgrowth of the Tasian, though this is disputed. Scholars who support the link between the two point to similarities in ceramics and other evidence such as tool-making, while those who dismiss the claim argue that the Badarian was much more advanced and developed independently.

The people of the Badarian Culture lived in tents which were mobile, just like their ancient predecessors, but primarily favored stationary huts. They were farmers who grew wheat, barley, and herbs and supplemented their largely vegetarian diet through hunting. Domesticated animals also provided food and clothing as well as materials for tents. A large number of grave goods have been found from this period including weapons and tools such as throwing sticks, knives, arrowheads, and planes. People were buried in cemeteries and the bodies covered with animal hides and laid on mats of reeds. During this period food offerings and personal belongings were buried with the dead, indicating a shift in the belief structure (or at least in burial practices) where now the dead were thought to need material goods in their journey to the afterlife. Ceramic work was greatly improved during the Badarian Culture and the pottery they produced was thinner and more finely crafted than earlier periods.

Following the Badarian Period came the Amratian (also known as Naqada I) Period of c. 4000-3500 BCE which created more sophisticated dwellings which may have had windows and definitely had hearths, walls of wattle and daub, and windbreaks outside the main doorway. Ceramics were highly developed as were other artistic pursuits such as sculpting. The Blacktop Ware ceramics of the Badarian Culture gave way to red ceramics ornamented with images of people and animals. Sometime around 3500 BCE the practice of mummification began and grave goods continued to be left with the deceased. These advances were furthered by the Gerzean Culture (c. 3500-3200 BCE, also known as Naqada II) who initiated trade with other regions which inspired changes in the culture and their art. Bunson comments on this, writing:

Accelerated trade brought advances in the artistic skills of the people of this era, and Palestinian influences are evident in the pottery, which began to include tilted spouts and handles. A light-colored pottery emerged in Naqada II, composed of clay and calcium carbonate. Originally, the vessels had red patterns, changing to scenes of animals, boats, trees, and herds later on. It is probable that such pottery was mass-producred at certain settlements for trading purposes. Copper was evident in weapons and in jewelry, and the people of this sequence used gold foil and silver. Flint blades were sophisticated and beads and amulets were made out of metals and lapis lazuli (76).

Houses were made of sun-baked brick and the more expensive featured courtyards (an addition which would become commonplace in Egyptian homes later). Graves became more ornate with wood used in the graves of the more affluent and niches carved in the sides for votive offerings. The city of Abydos, north of Naqada, became an important burial site and large tombs (one with twelve rooms) were constructed which grew into a necropolis (a city of the dead). These tombs were originally built using mud bricks but, later (during the Third Dynasty) were constructed of large, carefully hewn, limestone; eventually the site would become the burial place for the kings of Egypt.

Even at this time, however, evidence suggests that people from around the country had their dead buried at Abydos and sent grave goods to honor their memory. The cities of Xois and Hierakonpolis were already considered old by this time, and those of Thinis, Naqada, and Nekhen were developing quickly. Hieroglyphic script, developed at some point between c. 3400-3200 BCE, was used for keeping records but no complete sentences from this period have been found. The earliest Egyptian writing discovered thus far comes from Abydos at this time and was found on ceramics, clay seal impressions, and bone and ivory pieces. Evidence of complete sentences does not appear in Egypt until the reign of the king Peribsen in the Second Dynasty (c. 2890-c.2670 BCE).

This period led to that of the Naqada III (3200-3150 BCE) which, as noted above, is also sometimes referred to as Zero Dynasty or the Protodynastic Period. Following Naqada III the Early Dynastic Period, and the written history of Egypt, begins.

![Narmer Palette [Two Sides]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/750x750/4412.jpg?v=1763087296-1721384182)

Naqada III & The Beginning of History

The Naqada III Period shows a significant influence of the culture of Mesopotamia whose cities were in contact with the region through trade. The method of baking brick and building, as well as artifacts such as cylinder seals, symbolism on tomb walls, and designs on ceramics, and possibly even the basic form of ancient Egyptian religion can be traced back to Mesopotamian influence. Trade brought new ideas and values to Egypt along with the goods of the traders and an interesting blend of Nubian, Mesopotamian, and Egyptian cultures was most likely the result (although this theory is routinely challenged by scholars of each respective culture). Monumental tombs at Abydos and the city of Hierakonpolis both show signs of Mesopotamian influence. Trade with Canaan resulted in Egyptian colonies sprouting up in what is now southern Israel and Canaanite influences can be determined through the ceramics of this period. Communities grew and flourished with trade and the populations of both Lower and Upper Egypt grew.

The small communities of brick homes and buildings grew into larger urban centers which soon attacked each other probably over trade goods and water supplies. The three major city-states of Upper Egypt at this time were Thinis, Naqada, and Nekhen. Thinis seems to have conquered Naqada and then absorbed Nekhen. These wars were fought by the Scorpion Kings, whose identity is contested, against others, most likely Ka and Narmer. According to some scholars, the last three kings of the Protodynastic Period were Scorpion I, Scorpion II, and Ka (also known as 'Sekhen', which is a title, not a name) before the king Narmer conquered and unified lower and upper Egypt and established the first dynasty.

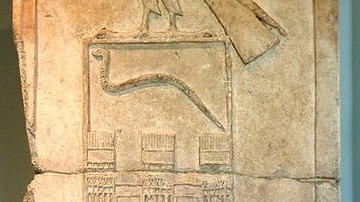

Narmer is now often identified with the king known as Menes from Manetho's chronology but this claim is not universally accepted. Menes' name is only found in Manetho's and the Turin King List chronology while Narmer has been identified as an actual Egyptian ruler through discovery of the Narmer Palette, a year marker bearing his name, and his tomb. Menes is said to have conquered the two lands of Egypt and built the city of Memphis as his capital while Narmer allegedly united the two lands peacefully. This is a curious conclusion to arrive at, however, since a king definitely identified as Narmer is depicted on the Narmer Palette, a two-foot (64 cm) inscribed slab, as a military leader conquering his enemies and subjugating the land.

No consensus has been reached on which of these claims is the more accurate or whether the two kings were actually the same person but most scholars favor the view that Narmer is the 'Menes' of Manetho's work. It is also claimed that Narmer was the last king of the Predynastic Period and Menes the first of the Early Dynastic and, further, that Menes was actually Hor-Aha, listed by Manetho as Menes' successor. Whichever is the case, once the great king (Narmer or Menes) united the two lands of Egypt, he established a central government and the era known as the Early Dynastic Period was begun which would initiate a culture lasting the next three thousand years.