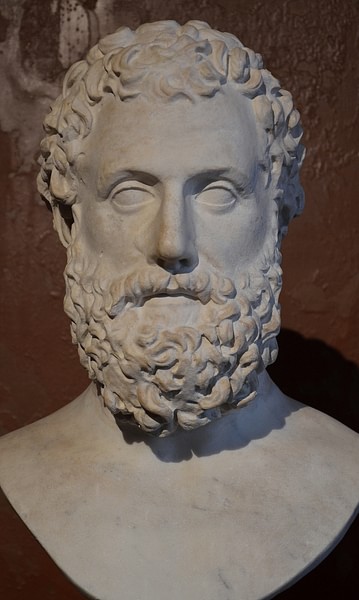

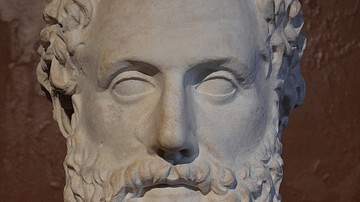

The Greek dramatist Aeschylus (c. 525 - c. 456 BCE) is considered one of the greatest tragic playwrights of his generation. He is often referred to as the “Father of Greek Tragedy.” Older than both Sophocles and Euripides, he was the most popular and influential of all tragedians of his era. Aeschylus authored over 90 plays; both tragedies and satyrs. Unfortunately, aside from a few fragments, only six complete plays have survived. Among his most famous remaining works are The Persians, Seven against Thebes, and Agamemnon, part of the Oresteia trilogy. A seventh surviving play Prometheus Bound is the subject of some dispute. As part of a trilogy together with Prometheus Unbound and Prometheus Firebringer, it was written around the time of Aeschylus' death; however, some scholars claim it was actually written by someone else, possibly his son Euphorion.

Aeschylus, the Father of Greek Tragedy

Aeschylus was born to an aristocratic family in 520 BCE near Athens in the town of Eleusis. Although he performed and composed some of his plays in Sicily, he would live his entire life in Athens. Little is known of his wife and family; however, both of his sons, Euphorion and Euaion were playwrights. According to classicist E. Hamilton, he was profoundly religious but somewhat radical, pushing aside the trappings of traditional Greek religion. The gods in his plays are seen as shadows, “questioning how a god can be considered just when people are allowed to suffer.” (193) For example, in Prometheus Bound Zeus is portrayed as a tyrant. This was the exact opposite of Hesiod's Zeus where he is depicted as a god of justice. Politically, Aeschylus was a strong supporter of Athenian democracy, a lover of freedom and justice. He fought against the Persians at Marathon in 490 BCE and at Salamis in 480 BCE. It was not until the early 490s that he began to write, participating in his first competition in 499 BCE, and finally winning his first victory in 484 BCE. Eventually, he won a total of 13 first-place victories, second only to Sophocles. He would continue to write until his death.

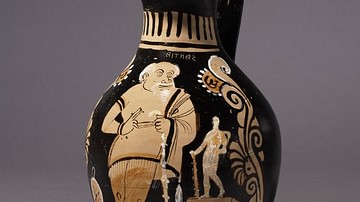

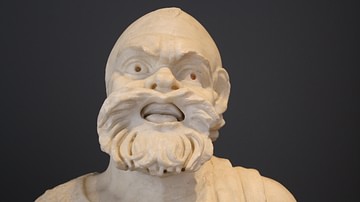

Like his contemporaries, his plays were often composed for competitions at various rituals and festivals and performed in outdoor theaters. The purpose of these tragedies was to not only entertain but also to educate the Greek citizen, to explore a political, social, or ethical problem. Along with a chorus of singers to explain the action, there were actors who wore masks and costumes. As with Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound and Sophocles' Oedipus the King, the audience was usually well aware of the story behind the play.

According to translator and editor, D. Grene, Aeschylus played a major role in “developing tragedy to its pinnacle of dramatic sophistication and moral power.” (2) Prior to Aeschylus, a play's dialogue was hampered with only one actor. With the introduction of a second actor, plot construction was given more freedom. Likewise, the intricacy and subtlety of plays increased. Unlike Sophocles and others, Aeschylus designed costumes, trained his choruses, and may have even acted in some of his own plays.

Main characters & The Myth

Prometheus Bound's cast of characters is few:

- the Titan Prometheus

- Hephaestus

- Ocean

- Io

- Hermes

- Might

- Violence (non-speaking)

- and, of course, the chorus.

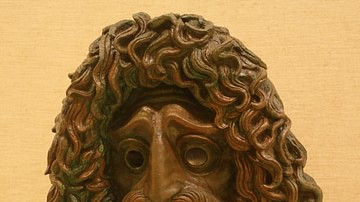

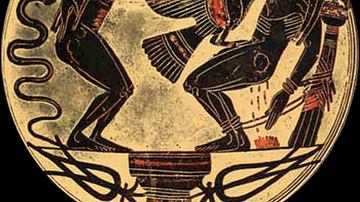

It tells of the plight of the Greek god Prometheus, son of the god Themis. The focus of the play is the battle between the supreme power of Zeus and the stubborn resolve of Prometheus. Prometheus had one fatal flaw and, for this, he would be tormented: he loved humans, and to save them from the wrath of Zeus, he stole fire, incurring the vengeance of the Olympian god. So, in a fit of anger, Zeus ordered Prometheus chained to a remote precipice where an eagle would come every night to feast on his liver. Throughout the play, he speaks to the chorus on his plight, defending why he had given mankind fire. He declares that through his gift of prophecy he sees a future that will bring the downfall of Zeus. At the end of the play, Prometheus is visited by the messenger of the gods, Hermes, who asks about the future he has foreseen and the fate of Zeus. Somewhat arrogantly, Prometheus refuses to tell and, in the closing of the play, is struck by the wrath of Zeus.

The plot

The play begins at a desolate crag in the Caucasus Mountains. A henchman of Zeus, Might, speaks to Hephaestus, the god of fire: “It's your job, now, Hephaestus, to carry out the commands the Father laid on you, to nail this malefactor to the high craggy rocks in fetters unbreakable of adamantine chain” (Grene, 173). But Hephaestus is reluctant and says he does not have the heart to do it, apologizing to Prometheus, warning him that he will neither hear nor see anyone and be burned by the sun's rays. He adds that nothing to say will change things, for “… the mind of Zeus is hard to soften with prayer, and every ruler's harsh whose rule is new” (174).

Might taunts Prometheus, saying the gods made a mistake when they called him "Forethought". He asks him what kind of help his mortals can offer to save him now. However, Prometheus stays strong defending what he had done for mankind, saying he will bear what fate has given him. Alone, he speaks out loud of his gift of fire to mankind:

I hunted out the secret spring of fire that filled the fennel stalk, which when revealed became the teacher of each craft to men, a great resource. (178)

This was the crime for which he is being punished. Speaking to the chorus, he laments, wondering why he had not been cast down into Hades instead. Bound to the crag, he is now the plaything of the winds. His enemies will be able to laugh at his suffering. However, he cries out that Zeus is savage and keeps justice according to his own standards. However, down deep, Prometheus knows that Zeus will one day be broken and come to him.

The chorus admonishes Prometheus, saying he speaks too freely. They continue, asking Prometheus to tell the story behind Zeus' punishment – why is he to be punished “so cruelly with such dishonor.” The Titan speaks of how he had followed his mother's advice and helped Zeus overthrow his fellow Titans; however, after ascending the throne, Zeus awarded each god with their “several privileges” but to humanity he gave nothing, intending on blotting them out.

I rescued men from shattering destruction that would have carried them to Hades' house and therefore I am tortured on this rock. (183)

He had felt pity for mortals but found none for himself. The chorus leader responds that his own heart was now pained. Riding in on a sea monster, the god Ocean gazes at Prometheus' plight, telling how he shared in the god's pains and wondered how he could be of help. Somewhat defensively, Prometheus questions if he was there to stare at his misfortune or offer pity. Ocean begs him to be silent, for if he continues to speak out, Zeus will hear and bring more pain. He begs him to “… give up this angry mood of yours and look for ways of freeing yourself from these troubles.” (187) Ocean says he will make a plea to Zeus to free Prometheus from his torment, but Prometheus responds, telling him not to bother. He adds that just because he is unlucky he does not want anyone else to be unlucky as well. He says that his heart was already sore. Prometheus relates the plight of his brother Atlas who supports the earth on his shoulders. He tells Ocean that he will bear the pain that Zeus has given him until the “mind of Zeus shall ease from anger.” He warns Ocean to be careful and that speaking to Zeus would be useless. With that, Ocean leaves.

Prometheus turns to the chorus and speaks of his kindness to mortals. He had found them mindless and made them intelligent, “masters of their own minds.” They had eyes but did not see any purpose; they had ears but could not hear. Speaking to the chorus he boasts that all human arts came from him.

With horns like an ox on her head, Io arrives. She asks Prometheus if he can hear the voice of the one-horned girl. Prometheus greets her and relates how the Zeus' desire for her made him turn her into a cow to avoid the wrath of his wife, Hera. Now she is haunted by a never-ending gadfly sent by Hera to punish her. She asks him why he is being punished. He replies that he was done telling that tale. Simply put, he is the giver of fire to man. Instead of speaking of his own dilemma, he asks her of her plight. She replies,

Why do I not throw myself at one from this rough crag to strike the ground and find release from all my troubles. (202)

Prometheus informs her that he will be released from his own problem when Zeus falls from power. Io asks how this will happen. Prometheus answers that Zeus will make a marriage that he will regret. His wife (it will not be Hera) will bear a son that will be mightier than his father. And, this person will be a descendant of Io. Prometheus gives her instructions: she is to go to Egypt where Zeus will restore her mind and touch with a hand that “brings you no fear.” In future generations, a descendant of that child will overthrow his father, Zeus. To the chorus, Prometheus speaks:

Yet shall this Zeus, for all his arrogance, be humble yet, such is the match he plans, a union that shall drive him from his power and from his throne… (209)

After Io leaves, Prometheus declares aloud that only he can tell Zeus how to avoid his destiny. Prometheus would not be alone for long. He is joined by the messenger of the gods, Hermes. Zeus has learned of the prophecy, but when Hermes asks, Prometheus refuses to speak of it. Hermes tells Prometheus that his attitude is what got him his present condition. Prometheus says that there is nothing Zeus can do to change his mind until “these atrocious shackles have loosed.” Hermes informs Prometheus of Zeus' curse upon him - to have an eagle come each night to eat his liver. Hermes adds that the proud Prometheus must heed the warning and not to blame Zeus but himself for what the future may bring. As Hermes leaves, there is thunder and lightning in the background. Prometheus ends the play saying,

Such is the storm that comes against me plainly from Zeus to work its sorrows. O holy Mother, O Sky that circling brings light to all, you see how unjustly I suffer. (216)

Legacy

Few would doubt that Aeschylus had a profound effect on Greek tragedy as an art form. He was the most influential and innovative tragedian of his generation. Prior to him, plays were limited; with only one actor and the chorus, interaction between characters was impossible. This limited conversation with an actor only speaking only to the chorus. With the addition of a second actor by Aeschylus, conversation between performers was now possible. This major change allowed for an increase in dramatic tension and plot development. After his death, his son, playwright Euphorion, restaged many of his plays. The Athenians respected his work so much that they passed a special decree allowing his plays to be performed annually at rituals and festivals. According to Grene, in the 18th and 19th centuries CE intellectuals rediscovered Aeschylus. Attention was given to his religious questioning and presentation of moral and political problems, and his plays are often seen as the foundation of Western drama.