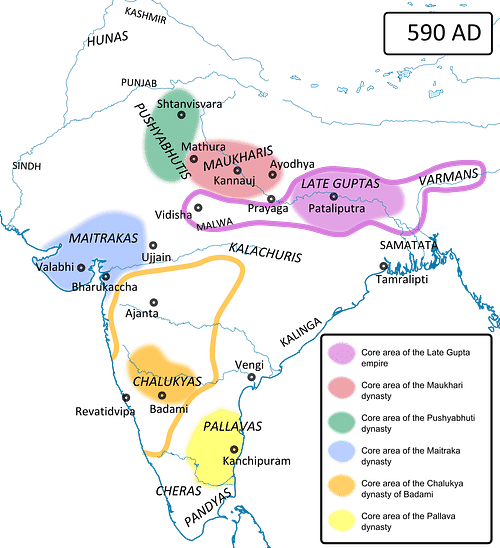

The Pushyabhuti Dynasty (c. 500 CE - 647 CE) rose after the downfall of the Gupta Empire (3rd century CE - 6th century CE) in the 6th century CE in northern India. Also known as the Vardhana or Pushpabhuti Dynasty, the core area of their kingdom was situated in what is now the state of Haryana in India with the capital at Sthanishvara or Thaneshvara (present-day Thanesar), and later at Kanyakubja (modern-day Kannauj, Uttar Pradesh state). The most notable ruler of this dynasty was its last ruler, Emperor Harshavardhana or Harsha (r. 606-647 CE). The Pushyabhutis established a powerful kingdom vying with other regional powers for political supremacy in India and, under Harsha, achieved imperial status. However, it was short-lived, and Kannauj came to be known ultimately as the base kingdom for future empires.

Political Conditions in 6th-century CE India

The fall of the Gupta Empire and the absence of any other empire in its stead led to the political disintegration of northern India. Along with the Pushyabhutis, there rose a number of similarly independent powers: the Maukharis of Kosala/Kanyakubja (present-day state of Uttar Pradesh), and the Later Guptas of Magadha and Malwa (present-day states of Bihar and Madhya Pradesh). The other kingdoms included those established in the present-day states of Odisha, Bengal, and Assam. In the 7th century CE, the Gauda kingdom under King Shashanka (c. late 6th century CE - 637 CE) came into being, comprised of the northern and most of the western parts of Bengal.

Early rulers

"The origin of the kingdom of Sthanishvara, modern Thaneswar, is shrouded in obscurity" (Majumdar, 96). Believed to have been founded by a certain Pushyabhuti, the early rulers are hardly known for any achievements. Inscriptions reveal that between the kings Pushyabhuti and Prabhakaravardhana, there were several unnamed kings and those who were known, like Naravardhana, Rajyavardhana, and Adityavardhana, who preceded Prabhakaravardhana. They ruled presumably from c. 500 - 580 CE and were feudatories of the Hunas (Huns), the imperial Guptas, and later of the Maukharis.

Besides inscriptions, two key primary sources for the Pushyabhutis exist. One is the account called Si-yu-ki left behind by the Chinese Buddhist monk-scholar Hiuen Tsang or Xuanzang (602-664 CE), who visited India in the 7th century CE and met Harsha. His account includes details of his court, of contemporary life and of economic, social and religious conditions. The other and more important is the Harshacharita or the biography of Harsha written by his court poet Banabhatta or Bana (c. 7th century CE), where much mention is made of King Prabhakaravardhana and his sons Rajyavardhana and Harsha and daughter Rajyashri. "With the accession of Prabhakaravardhana, the history of Thaneshvara assumes a definite shape, thanks to the biography of Harsha (Harshacharita) written by the contemporary scholar, Banabhatta" (Majumdar, 97).

Prabhakaravardhana

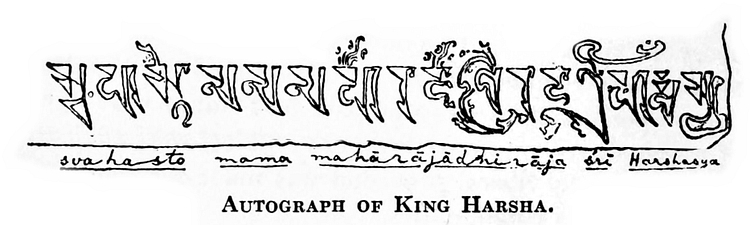

Prabhakaravardhana (r. 580-605 CE, also known as Pratapashila) is described by Bana as "a proud man, he was vexed by his proud ambitions" (Banabhatta, 101). He thereby fought many enemies and expanded his kingdom and assumed the title Maharajadhiraja (Sanskrit: "Lord of Great Kings"), the first in the dynasty to do so. He took advantage of the eclipse of Maukhari power after the death of King Ishanavarman (c. 6th century CE) but maintained cordial relations with them, marrying Rajyashri to the contemporary Maukhari king Grahavarman (c. 6th century CE - early 7th century CE).

He was at war frequently and is believed to have fought the Hunas in present-day northern Punjab and the kings of Sindh and Gandhara (present-day Pakistan) and of Lata (present-day southern Gujarat) and Malwa. It is not clear as to whether he actually defeated them or merely fought a defensive war with them, but in his time, he made the Pushyabhutis a power to reckon with. He died from an illness and was succeeded by his elder son Rajyavardhana (r. 605-606 CE).

Rajyavardhana

As a prince, Rajyavardhana was sent on a campaign against the Hunas but had to return to the capital due to his father's illness. As king, he was faced with an unexpected war. The Later Guptas, old enemies of the Maukharis, had allied with Gauda and together, they marched against Kanyakubja and attacked and killed Grahavarman in 606 CE. Devagupta, the Later Gupta king, then occupied Kanyakubja and imprisoned Rajyashri. Rajyavardhana marched with his army to defeat him and rescue her. He reached Kanyakubja and defeated the Malwa army en route, possibly killing Devagupta "with ridiculous ease" (Banabhatta, 209). The Harshacharita states that Shashanka came to his aid and murdered Rajyavardhana "who had been allured to confidence by false civilities on the part of the King of Gauda, and then weaponless, confiding, and alone, despatched in his own quarters" (Banabhatta, 209).

Harshavardhana

Prince Harsha, knowing of his brother's murder, swore vengeance on Shashanka who by then had occupied Kanyakubja and declared war. He marched with his army and concluded a treaty with King Bhaskaravarman (r. 600-650 CE) of Kamarupa (present-day Assam state). The unfinished Harshacharita is silent on what happened as regards this war; "Indeed, the court poet does not even inform us how his patron proceeded against the Gauda king, who was the immediate object of his wrath" (Tripathi, 296). It appears that at that point, Shashanka fearing the combined might of Harsha-Bhaskaravarman and his own weak position, especially after the rout of the allied Malwa army, withdrew from the contest. Harsha managed to rescue his sister and occupy Kanyakubja.

It is believed that Avantivarman, Grahavarman's younger brother, succeeded to the throne (possibly as regent), and after his death, Harsha became the king of the Maukhari realm. He first administered the realm in the name of his sister Rajyashri, the queen of Grahavarman, and later assumed full sovereignty and openly assumed the crown. The capital too was shifted from Sthanishvara to Kanyakubja and the two kingdoms amalgamated into one. It is believed that Harsha had been the de facto king of the Pushyabhutis since 606 CE but only after subduing powerful enemies like Shashanka could he even think of coronation.

Military Campaigns & Expansion

Harsha's reign continued to be marked with warfare, but this time, with the enemies of his own choosing. He fought against Valabhi (present-day northern Gujarat and part of Malwa), Sindh, and the eastern kingdoms in Magadha (present-day Bihar) and in present-day Odisha. His ambitions soon met a worthy rival in King Pulakeshin II (r. 609-642 CE), ruling the Vatapi kingdom (present-day Badami, Kanataka state) in southern India. In a decisive battle fought in 618/19 CE or 634 CE, the Chalukyas defeated Harsha who was forced to retreat and could no longer expand southwards. The defeat did not deter him from reaching out for territory in eastern India and "he had to undertake military expeditions almost till the close of his momentous reign" (Tripathi, 298).

The Pushyabhuti kingdom consisted of most of present-day Uttar Pradesh state and parts of Bihar. The inclusion of the Maukhari realm added to its dominions. Prabhakaravardhana's kingdom was "bounded by the Yamuna (or the Ganga) and the Beas on the east and the west, and the Himalayas and Rajputana on the north and the south" (Majumdar, 98). Harsha increased the boundaries, and "Rajasthan, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Odisha were under his direct control, but his sphere of influence spread over a much wider area" (Sharma, 171). Though the Sanskrit epithet 'Sakalottarapathanatha' ('Lord of the entire northern country') has been used for Harsha, he did not control the whole of northern India. His defeat by Pulakeshin checked his southern ambitions and permanently ended the Pushyabhuti entry into southern India.

Harsha did not leave behind any heir, and the Pushyabhuti line came to an end. Power was seized by one of his ministers who, after unsuccessfully fighting the Chinese, was taken captive by them, and "with it the last vestiges of Harsha's power also disappeared" (Tripathi, 314). While Kanyakubja remained as a kingdom and once more came into the limelight under King Yashovarman (r. 725-753 CE), most of Harsha's feudatories and friends like Bhaskaravarman parcelled out the empire and added the conquered bits to their own kingdoms.

Religion & Government

Hinduism and Buddhism were the chief religions. Harsha himself was "neither a staunch Hindu" (Sharma, 171) and openly patronized Mahayana Buddhism, giving a warm welcome and special privileges to Hiuen Tsang. He also organized a grand assembly at Kanyakubja to allow Hiuen Tsang and others to speak about the greatness of Mahayana. He also distributed alms after every six years, a practice which went on for days until the entire treasury was exhausted, even down to the emperor's own clothes. Legend has it that after giving them away, Harsha would turn to Rajyashri asking her to donate clothes to him to wear.

By the time of Harsha, the Pushyabhuti administration, which had earlier worked on the imperial Gupta pattern, became more feudal in nature and highly decentralized. Harsha's inscriptions mention many kinds of taxes and officials. Officials were rewarded with grants of land, which explains why Harsha issued a lesser number of coins as compared to other rulers. The vast resources of the Maukhari kingdom once in the hands of Harsha enabled him to carry out his own conquests in various parts of India. The control of Kanyakubja brought with it greater imperial control over the areas connected by the Ganges river, "the highway of traffic linking up all the country from Bengal to mid-India" (Tripathi, 301) and hence created greater prosperity in terms of commerce and economy.

Nobles and generals had a say in administrative matters and the king was duty-bound to listen to them. The Harshacharita mentions such notables as the generals Bhandin or Bhandi and Simhanada, who openly voiced their opinions on matters of state and advised the princes on the next course of action, which was often followed.

Harsha was a patron of the arts and learning. He made huge endowments to the Nalanda university and to intellectuals and scholars. Under him, poets such as Bana flourished and composed many literary works. Harsha himself is believed to have written three plays called the Priyadarshika, Ratnavali, and Nagananda. However, many historians doubt his scholarship and instead believe that they were ghostwritten by a poet called Dhavaka.

Army

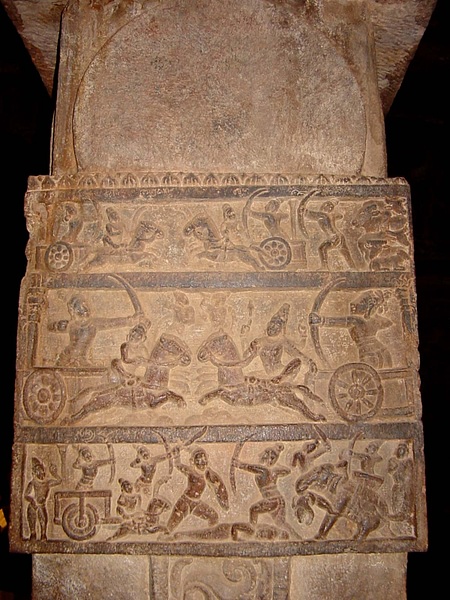

The army in this period consisted of elephants, cavalry, and infantry. Vast numbers were provided by feudatories, and so it is believed that Harsha had 100,000 horses and 9000 elephants. The Harshacharita is full of descriptions of weapons and the love that the Pushyabhuti rulers had for their swords, for war and for showing prowess in battle. Prabhakaravardhana made the Pushyabhutis a military power. His armies are described by Bana as "levelling on every side hills and hollows, clumps and forests, trees and grass, thickets and anthills, mountains and caves" (Banabhatta, 101), thus showing that they were capable of long marches and through difficult terrain.

Cavalry and elephants were given much importance. Rajyavardhana marched against the Malwa army with a small but picked force of cavalry under Bhandin and utterly routed it. Bana devotes many pages to describing the horses and elephants possessed by his master and in particular, his favourite war elephant named as Darpashata who is described as Harsha's "external heart, his very self in another birth, his vital airs gone outside from him, his friend in battle and in sport, rightly named Darpashata, a lord of elephants" (Banabhatta, 52). However, they did not prove to be of much worth against the Chalukyas and their elephant corps.

Camps are also described in detail. The provisions, which included food, fodder, weapons, clothing, and camping materials, would be carried on bullock carts, elephants, mules, and camels and accompany the army. Often, such processes could be very chaotic. Technically, the cultivators, merchants, and villagers were to be left alone, but often, in practice, the soldiers would plunder the grains or merchandise, in which case complaints of the aggrieved could be put before the king who was supposed to take action.

Kings and princes were also adept in the art of fighting and warfare. Prabhakaravardhana is mentioned as a valiant warrior whose hands were hardened and callused by the repeated use of the bow on the battlefield. Bana comments:

The king one day summoned Rajyavardhana, whose age now fitted him for wearing armour…placed him at the head of an immense force and sent him attended by ancient advisers and devoted feudatories towards the north to attack the Hunas. For several stages my lord Harsha followed his march with the horse. (Banabhatta, 132)

It can be surmised that since much of the imperial Gupta style was still prevailing in the period, it could thus be very likely that the military system had not changed much. The soldiers wore their hair loose or tied back with a fillet or skull caps and simple turbans, with tunics, crossed belts on the bare chest or a short, tight-fitting blouse. The elites commanding the army or other officials wore armour (especially of metal). Shields were rectangular or curved and often made from rhinoceros hide in checked designs. Many kinds of weapons such as curved swords, bows and arrows, javelins, lances, axes, pikes, clubs and maces were used.

Legacy

Prabhakaravardhana's efforts made the Pushyabhutis a leading political power of the day and this was used by Harsha to build an empire in northern India, the first after the decline of the Guptas. Thus, "he succeeded in giving a measure of political unity to a large part of the country" (Sharma, 172) and was the most significant imperial ruler in the post-Gupta period. By making Kanyakubja the capital and developing it further as an imperial political and administrative centre, Harsha solidified the geographical shift, the first in many centuries, from Magadha in north-eastern India to Kanyakubja in north India. From the 6th century BCE, Magadha had been India's imperial heartland especially of the two great empires of the Mauryas (4th century BCE - 2nd century BCE) and the Guptas.

Kanyakubja continued as a centre of power under Yashovarman and, between 750-1000 CE, its importance reached such an extent that capturing it became the symbol of imperial power in India, even for geographically distant powers like the Pratiharas (8th century CE - 11th century CE) of north-western India, the Palas (8th century CE - 12th century CE) of eastern India, and the Rashtrakutas (8th century CE - 10th century CE) of southern India.