Quetzalcóatl (pron. Quet-zal-co-at) or 'Plumed Serpent' was one of the most important gods in ancient Mesoamerica. Quetzalcóatl was the god of winds and rain, and the creator of the world and humanity. A mix of bird and rattlesnake, his name is a combination of the Nahuatl words quetzal (the emerald plumed bird) and coatl (serpent).

In Central Mexico from 1200, the feathered serpent god was considered the patron god of priests and merchants as well as the god of learning, science, agriculture, crafts and the arts. He also invented the calendar, was identified with the Morning Star Venus, the rising morning star, he was associated with opossums and even discovered corn (maize) with the help of giant red ant that led him to a mountain packed full of grain and seeds. He was known as Kukulkán to the Maya, Gucumatz to the Quiché of Guatemala, and Ehecatl to the Gulf Coast Huastecs.

Quetzalcóatl was the son of the primordial androgynous god Ometeotl. In Aztec mythology he was the brother of Tezcatlipoca, Huizilopochtli and Xipe Totec. He is the 9th of the 13 Lords of the Day and is often associated with the rain god Tláloc. The god was particularly associated with the sacred site of Cholula, an important place of pilgrimage from 1200, and all round buildings of the Aztec culture were dedicated to the deity.

A Creator God

In the Late Postclassical period (from 1200) in Central Mexico the god came to be strongly associated with the wind (in particular as a bringer of rain clouds) and as the creator god Ehecatl-Quetzalcóatl. In Postclassical Nahua tradition Quetzalcóatl is also the creator of the cosmos along with either his brother Tezcatlipoca or Huitzilopochtli and is one of the four sons of Tonacateuctli and Tonacacihuatl, the original creator gods. After waiting for 600 years this aged couple instructed Quetzalcóatl to create the world. In some versions of the myth Quetzalcóatl and Tezcatlipoca repeatedly fight each other and as a consequence the four ages are created and destroyed with each successive battle between the two gods.

In an alternative version of creation Quetzalcóatl and Tezcatlipoca are more cooperative and together they create the sun, the first man and woman, fire and the rain gods. The pair of gods had created the earth and the sky when they transformed themselves into huge snakes and ripped in two the female reptilian monster known as Tlaltcuhtli (or Cipactli), one part becoming the earth and the other the sky. Trees, plants and flowers sprang from the dead creature's hair and skin whilst springs and caves were made from her eyes and nose and the valleys and mountains came from her mouth. In some versions of the story the divine spirit of Cipactli was understandably upset to have lost her physical body in such a brutal attack and the only way to appease her was through the sacrifice of blood and hearts and so one of the more unpalatable practices of ancient Mesoamerican culture, the ritual of human sacrifice, was justified.

Quetzalcóatl & Mictlán

In the myth of mankind's creation Quetzalcóatl descends into Mictlán - the underworld - where he is sent to remove some bones. However, Mictlanteuctli and Mictlancihuatl, the ruling gods of the underworld, agree to give the bones only if Quetzalcóatl can blow a conch-shell horn that has no holes in it. The clever Quetzalcóatl gets around the problem by having worms drill holes in the conch and putting bees inside to make it sound. Quetzalcóatl also pretends to leave the underworld without the bones, declaring his intention to leave them where they are whilst in actual fact he steals them from under the nose of Mictlanteuctli. The god is outraged at the deceit and makes a pit to entrap the trickster. Quetzalcóatl does indeed fall into the pit and in so doing scatters the ill-gotten bones so that the male and female parts are mixed. Gathering up the bones, Quetzalcóatl escapes the pit and gives them to the great snake goddess Cihuacóatl to magically fashion them into people by mixing them with corn and some of Quetzalcóatl's blood.

How is Quetzalcóatl Represented in Art?

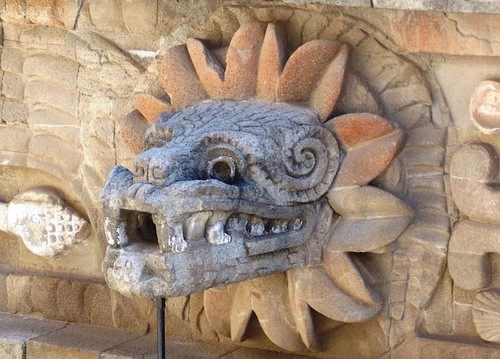

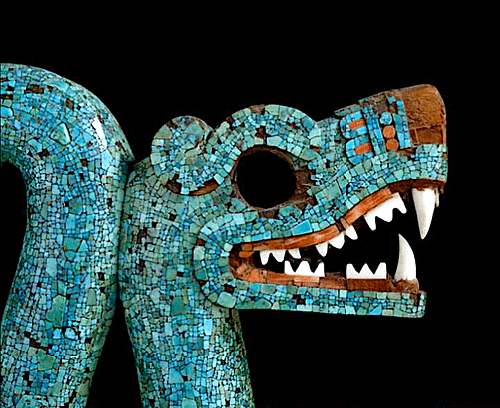

The earliest surviving representation of Quetzalcóatl is from the Olmec civilization with a carving at La Venta of a beaked snake with a feather crest flanked by two quetzal birds and a sky band. The earliest representation in Mexico is at Teotihuacán where there are 3rd-century representations of feathered snakes and where a six-tiered pyramid was built in the god's honour. These representations of the god and those at the later site of Cacaxtla include the god with rain and water suggesting a strong association with that element. The feathered snake god was often represented in architectural sculptural decoration and he appears at other sites such as Xochicalco but rarely with any human form before the Late Postclassical period, an exception is a carved palma from Veracruz.

From 1200 Quetzalcóatl is often represented in human form and usually wears shell jewellery and a conical hat (copilli). He may also have a hat-band holding sacrificial implements, a flower, a fan of black and yellow feathers and ear-rings of jade circles or spiral shells (epcololli). The god also often wears the wind jewel (Ehecailacozcatl) which is a cross section of a conch whorl worn as a pectoral. As Ehecatl-Quetzalcóatl he is often black, wears a red mask like a duck's beak and has long canine teeth. As god of the cardinal directions Quetzalcóatl was also associated with the colours black (north), red (east), blue (south) and white (west).

Following the Spanish Conquest, the already complex myths surrounding Quetzalcóatl became even more twisted, a situation not helped by the confusion of the god's history with that of the legendary first ruler of the Toltecs at Tollan, Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcóactl, who took on the name of the god as one of his titles. Even today the legend and symbolism of Quetzalcóatl lives on and he has become a beacon of Mexican national pride and a powerful symbol of indigenous tradition.