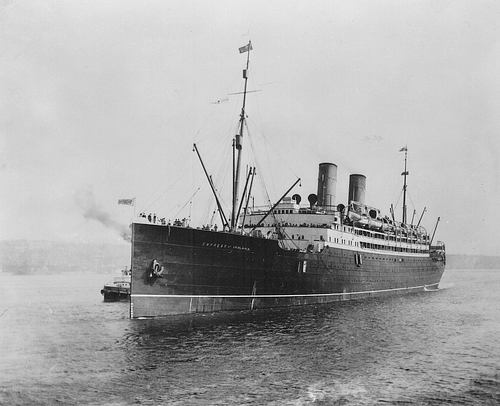

The RMS Empress of Ireland was a transatlantic passenger ship that sank early in the morning of 29 May 1914 on the St. Lawrence River killing 1,012 of the 1,477 people on board. It is considered Canada’s worst maritime disaster and one of the most tragic in history.

The event came two years after the RMS Titanic sank after striking an iceberg on 15 April 1912 taking over 1,500 lives. After the Titanic tragedy, measures were taken to ensure nothing like it would happen again. The Empress of Ireland was therefore equipped with more lifeboats than necessary and watertight longitudinal bulkheads which, in the event of an emergency, could be sealed so the ship would remain afloat even with two of the sections compromised. The crew were also highly trained to respond to a crisis and the ship was upgraded in 1912 with state-of-the-art safety devices, lifejackets, and new steel lifeboats.

All these precautions turned out to be meaningless, however, when the ship was struck by the Norwegian collier Storstad around 1:50 in the morning of 29 May 1914, tearing a large gash in the starboard side of the Empress that flooded the ship and sank her in under 14 minutes.

Unlike the Titanic, or the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915, the Empress of Ireland was largely forgotten soon after the disaster for reasons that are still debated. The most likely cause is considered the outbreak of World War I less than a month after the ship sank but it is just as probable that people did not wish to remember a ship that sank despite being fully equipped for passengers and crew to survive such an event.

Design & History

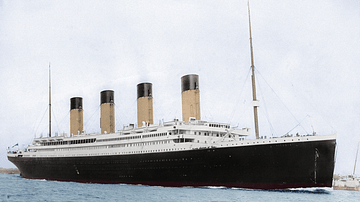

The Empress of Ireland was the sister ship of The Empress of Britain, both built in the Clyde Yard of the Fairfield Shipbuilding Company, Glasgow, Scotland. Both ships had been commissioned and were owned by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company (the CPR) which had decided to enter the competitive market of transatlantic travel in 1904. The two Empresses were completed and took their maiden voyages in 1906.

The two ships were identical at a length of 570 feet (170 m), 65 feet (20 m) wide, with a depth of 36.7 feet (11.2 m). and twin four-blade propellers. Scholar James Croall describes the ship:

The Empress was a twin-screw steamer of 14,000 tons…her quadruple expansion coal burning engines gave her a designed speed of 20 knots, and this she achieved in her voyages. The two sisters consistently made the 2,800-mile crossing between Liverpool and Quebec in about six days...The Empresses were handsome ships after the classic pattern of their age: straight stem, sweeping counter stern, two high, raking buff funnels with black tops, and tall, raking masts to match. They swiftly established a reputation not only for speed, but for their steady behavior in the worst Atlantic weather. The Empress of Ireland could carry around 1550 passengers: 300 or so First Class, 450 Second Class, and over 800 in Third Class. (11-12)

At the time of her sinking, The Empress of Ireland was on her 96th transatlantic run and had brought over 100,000 immigrants from Liverpool to Quebec and nearly 70,000 in the opposite direction. She was one of the most popular ships of her day for comfort, speed in travel, and affordability. A third-class passenger’s ticket cost 6.50 pounds, second-class 10.00 pounds, and first-class 14.00 pounds. Although third-class accommodations could not be compared with first-class, they were still considered more comfortable and spacious than those offered by White Star (owner of Titanic) or Cunard lines. Croall notes:

The Empress never aspired to the standards of ostentatious luxury that were the mark of the gigantic superships competing for the rich New York market, but they did establish an unchallenged reputation for something that early twentieth-century travelers understood and appreciated, namely solid comfort. (12)

Interior Appointments

First-class staterooms were located amidships on the upper deck and lower promenade decks which encircled the ship and were decorated with potted plants at intervals. First-class passengers had access to their own café, music room, smoking room (for the men) and a library shared with Second-class passengers. An orchestral stringed quintet played regularly at set times throughout the day for both classes. There was a separate dining room for children who were served by their own stewards.

Second-class accommodations were slightly less luxurious, set in the stern of the lower promenade and upper decks. They were purposefully designed to be re-furnished depending on the number of first-, second-, and third-class passengers on a given trip so they could be modified to the expectations and budget of any of the three. Second class had its own smoking room for the men and access to the first-class café.

Third-class travelers were housed below decks with their own smoking room and a ladies’ writing and music room. Their staterooms were spartan but comfortable and they had access to their own section of the upper decks which included a sandbox for children surrounded by a fence and benches for the parents. Third-class passengers made up the majority of any transatlantic crossing and CPR recognized the importance of making their trip as comfortable and enjoyable as possible, as Croall notes:

Enlightened shipping companies had realized that the migrant who was decently looked after on his lonely and often penniless pilgrimage in search of a better life was likely to be a repeat purchaser in Second or even First Class when one day he returned home to show the old folks how well he had done. (14)

Class divisions naturally kept the respective travelers in their own sections and there was no need for the ship’s crew to enforce this. Third-class passengers understood they had no place in first-class accommodations and, based on reports of the time, were perfectly content with their own.

Captain, Crew, & Passengers

The captain of the ship was Henry George Kendall (l. 1874-1965) who had decades of experience at sea, beginning at the age of 14. He had been captain of the SS Montrose and became a celebrity on both sides of the Atlantic when he recognized the murderer Hawley Harvey Crippen, a fugitive from London, aboard his ship and used the wireless to notify authorities who were able to apprehend and then hang Crippen. He was appointed captain of the Empress only a few weeks before her last voyage but was implicitly trusted by his crew and passengers for his reputation in command of other ships, not just his celebrity status owing to the Crippen case.

Richard Mansfield Steede had served the Empress as Chief Officer since her maiden voyage and John Edward Jones (First Officer) and Roger Williams (Second Officer) were similarly experienced. The crew numbered 420 with 16 engineers overseeing the engine-room. All of the crew were regularly drilled on emergency procedures and had only just performed such a drill in perfect time before the final voyage.

The passengers included 167 members of the Salvation Army band heading for London to a conference as well as the famous actor Laurence Irving and his equally famous wife, Mabel Hackney who had just completed a successful North American tour. The politician and sports-writer Sir Henry Seton-Karr was also aboard, returning home from a hunting trip, as well as other luminaries of the time such as the financial journalist Leonard Palmer and his wife. There were, in all, 1,057 passengers on board when the ship left its moorings at 4:27 on the afternoon of 28 May 1914.

The Storstad

The SS Storstad was a cargo ship transporting coal between Britain and Canada. Her captain since 1911 was Thomas Andersen and the First Officer, Alfred Toftenes, had served with him since the ship was commissioned. The ship measured 440 feet (134 m) long and 58 feet (17 m) wide and was built for long hauls carrying great weight. Croall comments:

Her main frames ran horizontally from stem to stern. Such ships were immensely strong, particularly in the event of a head-on impact of the kind that would often crumple the bows of a conventionally designed vessel. It was a very sensible arrangement in a ship which spent much of her working life plying in icebound waters. Unhappily, the heavy stem and thick shell plating that could slice through pack ice and shoulder it aside without damage would be equally effective at piercing steel plate. Her sharp vertical stem and massive frames made her in effect an immense cold chisel. (60)

In the early morning of 29 May, the Storstad was carrying 11,000 tons of coal in her hatches and traveling low in the water. Captain Andersen and his wife had retired for the night at around 10:00 pm on the 28th, leaving First Officer Toftenes in charge on the bridge. The ship was traveling upriver toward Quebec as the Empress was coming downstream.

Collision

The evening aboard the Empress had been uneventful. At 5:30 pm on the 28th, the Third-Class passengers were served high tea, a full meal of meats and herring with dessert, and at 7:00 pm formal dinner was served for the First and Second-Class passengers. After dinner, people walked the promenade decks and went to the smoking rooms, writing rooms, cafes, and bars. By 10:00 pm, most of the passengers were asleep in their rooms and by midnight almost all were. The ship reached Pointe-au-Pere sometime after midnight where they dropped off the pilot, who had navigated the St. Lawrence up to that point, and then continued on.

What happened next is still debated as the reports of the two captains, as well as survivors of the Empress and the crew of the Storstad, differed. It seems Captain Kendall saw the lights of the Storstad some miles ahead and changed course because he was then toward shore and preferred to pass the other ship mid-river starboard-to-starboard instead of port-to-port. The Storstad held its course upriver.

Shortly before 2:00 am, a fog rolled across the river and hung thickly, completely obscuring the vision of the two crews. Kendall ordered blasts from the ship’s horn to let Storstad know where the Empress was and that it was going Full Stop. Storstad responded with an acknowledging blast. The last time Toftenes had seen the Empress, however, she was port side, and the fog distorted the direction the blasts had come from. He ordered a course change to starboard to avoid any chance of colliding with the Empress which he thought lay ahead to port.

On board the Empress, Kendall and his crew suddenly saw the Storstad emerge from the fog on a direct course for the Empress’ midships. Kendall shouted through his megaphone for the Storstad to go full speed astern to try to minimize damage, but the collier struck between the funnels, cutting a 16-foot-long vertical gash in the hull of the ship. Kendall then shouted for the Storstad to keep its engines at full speed to plug the hole but, upon seeing the other ship, he had quickly ordered Empress full speed ahead.

The Empress began to move just as she was struck and the momentum of the collision, as well as the currents of the river, pulled the Storstad away and upriver. The icy waters of the St. Lawrence rushed through the gash in the Empress’ side at a rate of 60,000 gallons per second. Kendall ordered the wireless operators to send out the SOS and, according to his report, ordered the watertight bulkheads closed.

Sinking

Almost immediately, the lights on the Empress went out and anyone below decks had to find their way up in total darkness as the ship filled with water and listed sharply to starboard. The state-of-the-art watertight bulkheads were useless because they needed to be closed manually and there simply was not time because the ship was sinking too quickly. The lifeboats were equally useless as the Empress was listing at such an angle that the boats on the port side swung over the deck and could not be lowered while many of those on the starboard side were already immersed or slid down the deck into the river. Portholes, open for the evening air, hastened the sinking of the ship as water poured into them.

Most of the third-class passengers would have drowned almost before they knew what was happening and even many of those on the upper decks must have drowned quickly, disoriented in their dark staterooms. According to different reports, between five and seven starboard lifeboats were launched while survivors, flung into the water, found others floating free. Kendall maintained command and organized abandoning the ship as best he could, but it was going down too quickly for any effective response.

Passengers who managed to scramble through the total darkness below decks, up the now-sideways stairways, onto the main deck, found themselves pitched into the river or hurled against bulkheads. The portside lifeboats released from their davits, sweeping some people into the water, possibly including First Officer Steede who remained at his post on the port side directing passengers to safety until the last. Henry Seton-Karr was last seen handing his life vest to another passenger and went down with the ship. Laurence Irving and his wife clung to each other as they leaped overboard but both were drowned.

The Storstad, after disengaging from the Empress, launched her lifeboats and began rescue efforts. Toftenes had called the captain to the bridge at the collision and Andersen organized the lifeboats while his wife gathered whatever dry clothing and blankets she could find to help survivors. The Storstad’s lifeboats, according to all reports, were launched quickly and returned to the ship filled over capacity with survivors, all either nearly naked or in nothing but a light nightgown, as quickly as they could. By this time, however, most of the passengers were drowned and, 14 minutes after the collision, the Empress sank beneath the St. Lawrence.

Aftermath

Other ships on the St. Lawrence, as well as people on the shores, responded quickly with rescue efforts but injuries sustained when the Empress listed so suddenly, as well as those afterward and the freezing cold waters, claimed 1,012 lives. Of the 420 crewmembers, 248 survived, including Kendall, 217 passengers survived out of 840, and only four of the 138 children on board survived the sinking. Survivors were treated at Rimouski where bodies were also brought for identification. Historian Logan Marshall describes the scene at Rimouski:

A glance at the corpses taken in a walk along the line revealed the story of the collision and the incidents following. Almost all bore marks of violence inflicted by contact with parts of the wrecked ship or in struggles in the water. There were bodies of women whose heads were split open or gashed. It is possible that women running from their staterooms in the darkness following the collision ran against stanchions or were hurled against the walls or the sides of the corridors. The wounds also indicated that some of the women had been crushed when the collier buried her steel nose in the side of the Empress. (81)

As with Titanic’s sinking, people were eager to assign blame and find a reason for the tragedy. A Commission of Inquiry began on 16 June 1914, presided over by Lord Mersey, who had also been the magistrate at the Titanic hearings. After eleven days, the Commission returned a report holding First Officer Toftenes of the Storstad to blame for changing course and for not calling Captain Andersen to the bridge when the fog obscured visual confirmation of the Empress’ location. A Norwegian Commission of Inquiry absolved Andersen and Toftenes of any responsibility and blamed Kendall for changing course and then stopping his ship dead in the water.

Conclusion

The sinking of the Empress of Ireland resulted in design changes to ships' bows, bringing the pointed stem up to the main deck instead of where it had been below the waterline. Longitudinal bulkheads were also modified and then discontinued as they were understood to have contributed to the disaster. Under normal conditions, the longitudinal bulkheads would have been effective but, compromised as they were, they doomed the ship. Measures were implemented afterwards to correct this design which investigators concluded had been a serious flaw, seemingly ignoring the particular circumstances of the Empress’ sinking.

The Storstad was repaired, refitted, and sold to pay costs from lawsuits. It was recommissioned but sank on 8 March 1917 after it was torpedoed by a German U-boat during World War I. The Empress’ twin, The Empress of Britain, continued to carry passengers until World War II when she was requisitioned as a troop transport ship. She also sank after being torpedoed by a U-boat on 28 October 1940.

Today, The Empress of Ireland rests at 130 feet below the surface of the St. Lawrence River with the remains of many who went down with her in 1914 still below decks. Unlike Titanic, the sinking of the Empress did not evoke worldwide shock or outrage as World War I began so soon afterwards. As noted, however, the most probable reason why the Empress was so quickly forgotten is because its sinking challenged any concept of safety, security, or precaution one could take – not just in transatlantic travel but in anything – since every measure which could have been taken had been and yet none were able to save the 1,012 people who died in the early morning hours of 29 May 1914.