The RMS Titanic was a White Star Line ocean liner, which sank after hitting an iceberg on its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York on 15 April 1912. Over 1,500 men, women, and children lost their lives. There were 705 survivors. In 1985, the Titanic wreck was found several miles deep on the Atlantic seafloor by Robert D. Ballard.

The largest ship built at the time, Titanic was considered of such a prodigious size and so well-built that it was ‘unsinkable’. Nevertheless, the ship hit an iceberg in the mid-Atlantic, which ripped a gash in the hull below the waterline that allowed tons of seawater to sink it in a matter of hours. Although carrying more lifeboats than the regulations stipulated, these were not enough to remove all passengers and crew from the stricken vessel. The Titanic disaster, still the worst peacetime sinking ever, shocked the world and led to a major overhaul of ship-building regulations and innovations for safety at sea.

Design

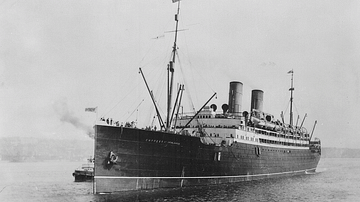

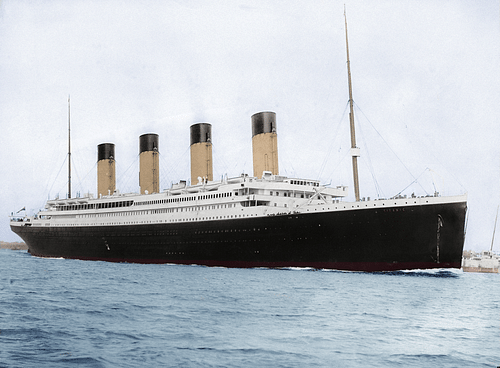

The Royal Mail Ship Titanic was an Olympic-Class passenger liner, its sister ships being the RMS Olympic and RMS Britannic. Titanic was launched from the Harland and Wolff shipyards in Belfast, Northern Ireland on 31 May 1911. The ship was built using 300 frames covered with 2,000 plates of steel attached using 3 million rivets. To make it practically unsinkable if damaged in any part of the hull, the interior was divided into 16 watertight compartments, which could be sealed off using electric doors. These doors could be closed independently of each other and were operated either from the bridge or manually. Even if two compartments were hit and flooded, the ship would remain afloat. It certainly seemed that it would take an extraordinary event to ever put Titanic’s passengers in danger at sea. Just in case the worst did happen, the ship was appointed lifeboats. With 20 lifeboats (capacity 1,178 persons), these were more numerous than the regulations stipulated (minimum 16). Although not enough for a full complement of passengers and crew, it was thought at the time that if ever needed, they would function only as a means to ferry people from the ship to a nearby rescue vessel.

Titanic was 269.1 metres (882 ft 9 in) in length and lived up to its name with a displacement of 66,000 tons. The main anchor alone weighed 15.5 tons. Equivalent to an 11-story building, the ship was the largest moving object made in history up to that time and so big a new dock had to be built at its homeport of Southampton. The tremendous power needed to propel such a giant came from two reciprocating steam engines and a low-pressure turbine. Combined, these gave the three screw propellors a massive 55,000 horsepower and a speed of 24-5 knots.

Interior Appointments

The size of Titanic gave the ship’s designers plenty of space to work with as they appointed the vessel in luxurious style. The facilities for passengers were unheard of and breathtaking in their scope and workmanship. Titanic boasted Turkish baths, a gymnasium, squash courts, two covered promenade decks, and even a swimming pool. The opulence of the first-class dining rooms, lounges, and reading room outdid any of the grandest hotels on land. A typical first-class menu included oysters, filet mignons, sirloin steak, pate de foie gras, and freshly made cream cakes. The double-stairway and glass cupola of the main dining room gave the illusion passengers were entering a palace. This staircase was a marvel of engineering in itself and descends seven decks into the bowels of the ship.

Cabins for first- and second-class passengers were unprecedented in their appointments and decoration. The better cabins had such wonders as electric heaters, extra-wide beds, marble washstands, and adjoining rooms for servants. Third-class passengers never saw any of these facilities down in steerage, but they did at least benefit from cabins and more comfort than their peers on other liners who had to make do with dormitories.

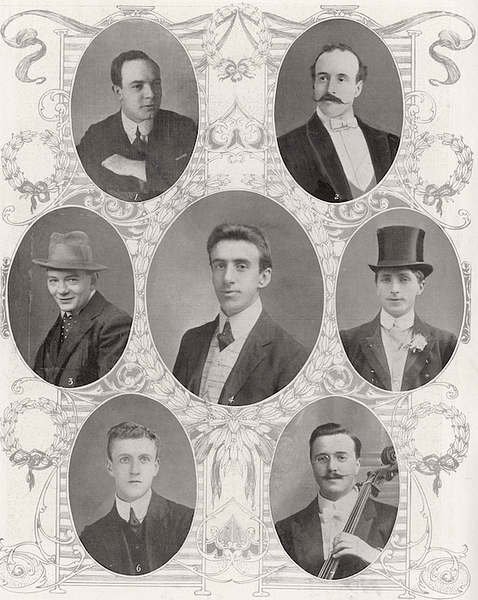

Passengers & Crew

Titanic's captain was Edward J. Smith, the most experienced captain of the White Star Line and a very popular figure with everyone on his ships. Smith, the company’s number one choice for maiden voyages, was to retire after this trip. Keeping a careful eye on their ship were the chairman of the White Star Line himself, J. Bruce Ismay, and the managing director of Harland and Wolff, Thomas Andrews, who knew the ship inside out. All three must have been totally unprepared for the disaster to come, Smith had once stated: "I cannot imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder…Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that" (Lord, 55).

Famous passengers included billionaire businessman John Jacob Astor, one of the richest men in the world, the mining magnate Benjamin Guggenheim, and Congressman Isidor Straus, owner of Macy’s in New York, the world’s largest department store. There was the publisher Henry Sleeper Harper, cinema star Dorthy Gibson, tennis player Karl H. Behr, and Margaret Brown, the wealthy philanthropist known forever after the disaster as the ‘Unsinkable Molly Brown’. There were some near misses, too. Financier J.P. Morgan had cancelled his ticket due to illness, as had two members of the immensely rich Vanderbilt family, but they were too late to reclaim their luggage and a servant from the ship. Amongst the ordinary folk, there were 13 honeymooning couples and many people who had left their homeland, hopeful for a new start and a better life in the Americas.

The Greenland Iceberg

Titanic set off from Southampton on 10 April 1912, stopping at Cherbourg in France and then Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland on the 11th to pick up more passengers and the latest mail. The ship now had over 2,200 people on board, all eager to see the Americas, many for the first time in their lives.

All went splendidly well for the first four days. Then the ship’s radio officers received the first of six warnings that ice was in the Atlantic on 14 April. In response to these sightings by other ships, Captain Smith ordered Titanic to take a more southerly route. As an extra precaution, six lookouts were posted to scan the forward horizon. Crucially, though, the ship’s speed was not reduced, but this was usual for a liner when no actual ice had been spotted. The great liners promised their passengers luxury and speed. Titanic was steaming at around 22.5 knots across an unusually calm Atlantic. This tranquillity of the sea made it, along with a moonless night, very difficult for the lookouts to spot ice when there would be no telltale breaking waters against the bergs to give away their position. It was also a bitterly cold night.

Then, at 11.40 pm, lookout Fred Fleet, perched high up in the crow’s nest, saw an iceberg. Fleet telephoned the bridge with his fateful message: "Iceberg right ahead." The bridge, then commanded by First Officer William M. Murdoch, responded by signalling to the engine room to reverse the ship’s engines, turning hard to port and closing all watertight doors. One can imagine the horrified fascination on the bridge in the final seconds before impact. Even after contact, the ship’s officers and those passengers who had seen the iceberg, likely remained hopeful that disaster had been averted. Unfortunately, this was not to be. Murdoch signalled for the engines to come to a full stop.

Titanic hit the iceberg a glancing blow, which many passengers never felt at all. In retrospect, it may well have been better if the ship had maintained its course and hit the berg head-on, damaging only the front part of the hull. As it was, when the berg slid down the length of the steel ship, it ripped a 250-foot (76-metre) gash below the waterline. Some of the more experienced crew down below felt the shudder and surmised it might have been a break in a propellor blade. The silverware rattled in the upper dining rooms, below in the kitchens a tray of bread rolls was shaken to the floor. The first to be aware of the scale of the problem were those even deeper in the ship, the men working in boiler room six. There, torrents of seawater were quickly flooding the compartment. The men escaped to what they thought would be the safety of boiler room 5, but that, too, was letting in torrents of water.

The ship’s passengers were mostly blissfully unaware of the gravity of the situation. Those few first-class passengers still up in the lounge areas continued their card games. Others who had been woken by the shudder and the stopped engines, went back to sleep, perhaps after checking with their steward that all was well. A group of steerage passengers were throwing about chunks of ice fallen from the berg onto the starboard well deck. Other than that, for passengers who braved the cold night air, there was nothing untoward to be seen.

Disaster

Deep within the ship, though, there were sure signs of the scale of the problem. The lower stairwells were filling with water, which had now reached the post office and mailroom. Even the lowest and cheapest cabins began to relentlessly fill with icy seawater. Orders were given to put out the fires of the ship’s boilers. Boiler room number five had received a 2-foot long gash, but pumps kept the water at bay and eventually cleared the compartment. It was a temporary respite. Having together surveyed the damage and assessed the flooded compartments, Thomas Andrews explained to the captain that too much water had entered the ship, weighing it down at the bow. The inclination would eventually allow water to flood over the top of each watertight compartment in turn. However secure the ship looked at that moment, it was a mathematical certainty it would ultimately sink. Titanic could afford to have three of the first five watertight compartments flooded, even the front four together but very soon, all five compartments would be flooded. Titanic’s terrible fate was sealed, the question now was only how long would it take.

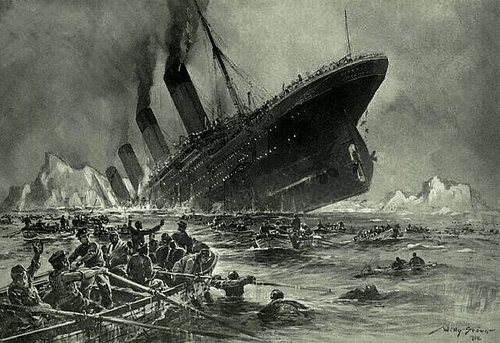

At 12.05 am, less than half an hour after the collision, Captain Smith gave the order to abandon ship. The ship's officers prepared the lifeboats for lowering, passengers and crew were roused if they still slept, and the order for lifejackets to be put on was given. Some put on sensible warm clothing, some grabbed their valuables and mementoes, others left behind fabulous jewels. Finally, the enormity of the situation was clear to everyone, even if some passengers were too stunned to comprehend. Everyone, whether escorted by their servants or smashing locked doors to get there, made their way to the open decks of the ship.

Titanic was two-thirds through the voyage and so surrounded by the icy waters of the Atlantic. Further, the drop from the boat decks to sea level was around 70 feet (21 metres), and there had never been a boat drill. This was not an enticing prospect for many passengers - spending the night in a small lifeboat seemed infinitely worse than staying onboard the ‘unsinkable’ vessel until help arrived. Consequently, not all lifeboats were lowered full.

Women and children were encouraged to step into the lifeboats first, then couples and then single men if there was still space. Some women refused to leave their husbands, others were persuaded to go for the sake of their children, still others were physically pushed into the boats by the crew. Many families were split forever this night. Then, as the ship did indeed begin to sink at the bow and the deck noticeably started to slope both forward and to starboard, passengers gathered in greater numbers at the lifeboats. To reduce panic to a minimum, a number of the ship’s musicians played ragtime music on deck. Fortunately, perhaps, neither the passengers nor most of the crew were aware that the sixteen rigid lifeboats and four collapsibles, even if all filled and lowered successfully, would still leave over a thousand people on board.

At 12.15 am the ship’s wireless operator was ordered to send out distress signals. Several vessels acknowledged the messages. The closest ship, some 21 miles away (33 km), was the 6,000-ton liner Californian, but its wireless was, as usual, shut down for the night. The ship was also at a standstill, blocked by an ice field. Titanic’s crew could see it and sent a morse code message using a lamp. The Californian did reply with a morse lamp, but the ships were too far apart to discern the message. The Californian’s crew did see the rockets fired off by Titanic every five minutes but they were not recognised for what they were, a distress signal, then still a new idea in maritime procedure. The Carpathia was 58 miles (93 kilometres) from the scene and did respond at 12.25. The ship made for Titanic’s position, exceeding its top speed by three knots. Titanic's wireless room kept sending out signals, and at 12.45, with nothing to lose, operator John George Philips tried the new SOS signal, the first time it was ever used by a liner.

The rockets at least now convinced everyone on Titanic that the ship was indeed about to sink. As the number of lifeboats left diminished, some of the crew were issued with firearms. The inclination of the ship encouraged people to move towards the stern. Still, there were people below decks as steerage passengers had to find their way around locked gates meant to keep them out of first- and second-class areas under normal circumstances. Some preferred the calm of their cabins and to await their fate there. Down in the engine room, men worked to keep the lights of the ship running, and Philips tirelessly kept sending out signals on his wireless. It was now 1.20 am, and almost all the boats were away, holding station a safe distance from the ship, their passengers looking on in horror at Titanic’s chaotic final moments, all to the bizarrely jolly soundtrack of ragtime music as still the band played on. None of the musicians would see daylight again.

At 1.40 the passengers were all told to move to the starboard side to help redress the ship’s sloping. By now the rockets had stopped. As passengers scrambled and leapt into the last few boats being lowered, shots were fired into the air to keep the crowd back. At 2.05, the last boat away was a collapsible, in it one Bruce Ismay. The ship’s deck lights were losing their power and glowing red as silence descended on the ship, no more struggling with ropes and boats. At 2.10 the last wireless signal was sent. Captain Smith wandered amongst the remaining crew spreading the word that they were released from their duties and it was now 'every man for himself.' Some jumped into the sea but still the band played on. Some of the crew worked on freeing the last two collapsible boats that were impractically tied to the roof of the officer’s quarters. Ominously, the band switched from ragtime to hymns. At 2.18 the ship’s lights went out.

Around 2.20 am, the ship’s stern rose ever higher, the forward funnel broke off with a crack, and Titanic began its slide into the deep. Those who could tried to swim clear of the suction. Some boats returned to pick up a total of 13 swimmers, but these were soon dangerously filled, and the cries for help that rang out in the night air had to be ignored. In the freezing water, hypothermia eventually brought down a curtain of silence on the disaster.

When the Carpathia arrived on the scene just after dawn at 4.00, Titanic was nowhere in sight, just a mass of debris like deckchairs and lifejackets. 705 survivors were picked up from the lifeboats. Also collected were several hundred floating bodies. 1502 people had died. The survivors and corpses were taken to New York where one third remained unidentified.

Aftermath

Captain Smith went down with his ship, as he had always promised he would. Frederick Fleet, the lookout, survived. Such was chance. Those who survived were haunted by nightmares, guilt, and sometimes, especially men, accusations of having taken the place of a woman or child in the boats. There was also the uncomfortable truth that proportionally, far more men, women, and children from third class had died than from first or second.

Official inquiries into the disaster were organised in America and England. The results of their findings led to the creation of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea. Prominent features were regulations for 24-hour radio monitoring, the use of rockets as a distress signal, lifeboat drills for passengers, and the number of lifeboats ships should carry. Another lasting benefit was the creation of the International Ice Patrol to continuously survey the movements of icebergs across the Atlantic.

At the time, the Titanic disaster was more than a terrible loss of life at sea. It was a blow against humanity’s confidence in itself, in the faith that design and intelligence could master the elements. In this sense, the disaster was an end of a long run of engineering successes the world had witnessed. The loss of the ship, and one so well built and appointed, was but the beginning of greater disasters yet to come in the 20th century.

Finding the Titanic

The fate of Titanic has captured public imagination ever since that terrible April night. Commemorated in poems, songs and films, there was still one unanswered question: Where was the ship now? The Titanic story was not finished. Robert D. Ballard began his search for Titanic on the seabed using the latest in robotic submersibles. He was not the first to try, but nobody had yet been successful. Ballard’s budget and U.S. Navy backers gave him just 12 days to find the legendary ship over a massive search area which was 3.8 km (12,460 ft) below the surface. It was on 1 September 1985, day 10 of the search, that Titanic was found. The liner had snapped in two pieces just below the surface and then sank to the seafloor. The wreckage and debris were spread over a wide area with items ranging from porcelain cups to an empty pair of shoes. Subsequent expeditions by others began the controversial process of collecting over 5,000 items before they finally succumbed to the ravages of time and to extensively photograph the wreck before it disappears forever.