Ragnarök is the cataclysmic battle between the forces of chaos and those of order in Norse mythology, ending the world and killing most of the gods and their adversaries, leading to the birth of a new world. It has been claimed, however, that in pre-Christian Norse belief there was no rebirth after the fall of the gods.

Ragnarök ("Fate of the Gods") is also given as Ragnarokkr ("Twilight of the Gods") and is the pivotal event that ends the mythic cycle beginning with the birth of the gods of Asgard (the Aesir) and the creation of the Nine Realms of Norse cosmology. The gods established order and restrained the forces of chaos, but at Ragnarök, these forces break free, and even though the gods know they are doomed, they march to battle to save the world they have created.

The gods fail and most are killed, including Odin, Thor, Tyr, and Heimdall, but order is preserved, and a new world emerges from the destruction of the old. Traditionally, since the 13th century, Ragnarök has been understood as the end of the Nine Realms through dramatic climate changes, the breakdown of traditional values, and a final battle which destroys the present cycle of existence to birth a new one. After Ragnarök, the surviving gods return to the place where their city once stood, and the last surviving human couple repopulates the earth for a new age.

This vision of Ragnarök is almost certainly influenced by Christianity, and it is possible that an earlier understanding of the event ended with complete destruction without resurrection. This claim is challenged, however, as the Norse myths were passed down orally prior to the advent of Christianity in the region and there is no written record of how Ragnarök may have once been understood. In the present day, the event is best known through popular media including a film, video game, and a TV series all suggesting rebirth after death.

Origin & Sources

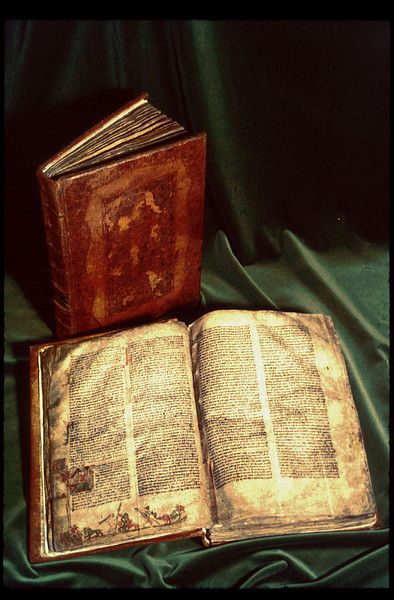

The story of Ragnarök is suggested through runestones dated to between the 10th-11th centuries – notably the Gosforth Cross in England, Thorwald’s Cross on the Isle of Man, and the Ledberg Stone in Sweden – and is only attested to in writing from the 13th century CE in the Poetic Edda and Prose Edda. The Poetic Edda is a collection of earlier Norse poems while the Prose Edda was composed by the Icelandic mythographer Snorri Sturluson (l. 1179-1241) from older sources and oral tradition.

Prior to the acceptance of Christianity in the region c. 1000, myths, legends, and histories were transmitted orally. Runes were used for memorial stones and brief messages, not for longer works, and so all extant Norse mythology was recorded through a Christian lens. Scholar John Lindow comments:

Scandinavian mythology was, with virtually no exceptions, written down by Christians…At least some of the monks were literate and they composed both Latin and Icelandic texts. Some lay persons of higher status were also apparently literate, at least in Icelandic, but all writing, whether in the international language of the church or in the vernacular, was the result of the conversion to Christianity, which brought with it the technology of manuscript writing. (10)

Even the poems from the compilation known as the Codex Regius ("King’s Book", written c. 1270), some dating to the 10th century and included in the Poetic Edda, were therefore written down either by Christians or scribes influenced by the Christian vision. Among these is the Völuspá ("The Witch’s Prophecy", c. 10th century) in which Odin summons a völva (seeress) who tells of the creation of the world, predicts Ragnarök, and describes its aftermath, including the rebirth of creation after the end of the present cycle.

Other works in the Poetic Edda, such as Baldrs Draumar ("Baldur’s Dreams"), Vafþrúðnismál ("The Lay of Valthrudnir"), and the Völuspá hin skamma ("Short Voluspa") also touch on or describe Ragnarök. These works, and others, were drawn on by Sturluson for his Prose Edda in which Ragnarök receives its fullest treatment in the section Gylfaginning, describing in detail the fall of the gods and the Nine Realms.

Norse Cosmology & Fate

At the beginning of time, there was only the World Tree Yggdrasil and the misty void of Ginnungagap bordered on one side by the fires of the realm of Muspelheim and on the other by the ice of Niflheim. The flames of Muspelheim melted the ice of Niflheim, revealing the giant Ymir and the cow Audhumla. Audhumla licked at the ice and uncovered the god Búri whose son Borr mated with the giantess Bestla resulting in the birth of the gods Odin, Vili, and Vé. At this same time, Ymir fertilized himself and gave birth to the race of the jötunn, some of whom were giants. Odin, Vili, and Vé killed Ymir and most of his offspring and then created the Nine Realms which Sturluson gives as:

- Asgard – Realm of the Aesir, joined to Midgard by the rainbow bridge Bifrost

- Alfheim – Realm of the elves

- Hel – Realm of those who died of illness or old age and then of most people

- Jotunheim – Realm of the giants and frost giants

- Midgard – Realm of the humans between Asgard and Jotunheim

- Muspelheim – Realm of fire, the fire giant Surtr, and Surtr's forces of chaos

- Nidavellir/Svartalfheim – Realm of the dwarves beneath the earth

- Niflheim – Realm of ice, snow, and mist near Muspelheim

- Vanaheim – Realm of the Vanir

These worlds existed in and about the roots of Yggdrasil at whose top lived an eagle and around the roots the serpent-dragon Nidhogg who gnaws at the tree. The eagle and serpent are kept in a constant state of enmity by the squirrel Ratatoskr who delivers false messages between the two, insulting each other. While this drama of the tree’s creatures plays out, the three Norns – the Fates – are also at work in the roots of Yggdrasil weaving the destinies of all living things, including the gods.

The Norse gods were not immortal, only exceptionally long-lived, and were kept young and healthy by the goddess Idunn and her magical apples. Periodically, they would have to eat of the fruit to ward off old age and retain youthful vigor. The Norns decreed that this practice would continue and the gods would remain forever young until the coming of Ragnarök, which would be heralded by the death of the fairest of the gods, Baldr.

Baldr’s Death & Loki’s Children

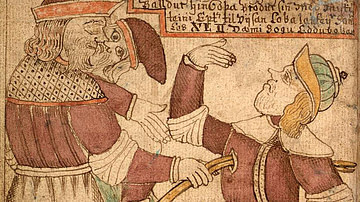

Baldr is the son of Odin and the goddess Frigg. In the poem Baldur’s Dreams, he has nightmares of some unseen doom to befall him and Odin rides Sleipnir down to the realm of Hel and raises the spirit of a seeress who tells him Baldr will soon arrive there. Sturluson expands on this story in the Prose Edda to include Frigg having bad dreams concerning her son at the same time. She makes all things in the Nine Realms, animate and inanimate, promise not to hurt Baldr but overlooks the mistletoe because it seems so harmless.

The trickster god Loki finds out about the mistletoe and brings a sprig back to Asgard where the gods are enjoying a game of hurling things at Baldr to watch them bounce off him harmlessly. Baldr’s brother, the blind god Hodr, cannot see to join in the game so Loki puts the sprig in his hand, directs his aim, and the mistletoe strikes and kills Baldr. The god Hermodr then rides Sleipnir down to Hel to ask Hel, Queen of the Dead, for Baldr’s return. She agrees on the condition that all things weep for his death. Hermodr almost succeeds in this, but a giantess named Thokk (who is actually Loki) refuses and so Baldr must remain in the realm of death.

Odin then mates with the giantess Rindr for the sole purpose of engendering the hero-god Váli who grows to full adulthood in a day and kills Hodr to avenge the death of Baldr. Váli then assists the other gods in tracking down Loki, killing his son Narfi and tearing out his intestines, using them to bind Loki in a cave where a serpent drips burning venom on his head.

Prior to Baldr’s death, Odin had ordered some of Loki’s other children, the wolf Fenrir, serpent Jörmungandr, and the jötunn Hel, taken from their mother in the realm of Jotunheim. Jörmungandr was thrown into the sea, Fenrir chained to a rock on an island, and Hel was sent to preside over the land of the dead below the realm of Niflheim. Once Baldr dies and cannot return to life, the clock begins ticking toward Ragnarök when Loki’s children, as well as their father, will break loose to attack the gods and the world of order.

The Twilight of the Gods

Baldr’s death was understood to have already occurred during the Viking Age (c. 790 - c. 1100) and people recognized they were living in the end times. Odin was thought to send his Valkyrie to claim the heroic dead from the battlefield as einherjar ("army of one") to feast and fight in Valhalla until the day they join the gods against the forces of chaos at Ragnarök. The goddess Freyja chose her own warriors for her realm of Fólkvangr, presumably for the same purpose, and so anyone who fell in battle was understood to have been taken to an afterlife where they would fight again heroically before dying a second death with most of the gods.

Although the stage was set for the end of the world after Baldr’s death, life would continue as it always had until certain signs appeared signaling the imminent approach of Ragnarök. Scholar Robert Carlson elaborates:

Human bonds of kinship as well as traditional beliefs will shrivel and disappear. A listless anarchy will evolve. Then there will be a period of time known as Fimbulvetr, characterized by three winters of increasing severity with no summers in between. Three roosters will crow: the crimson rooster Fjalar will crow to the Giants; the golden cock Gullinkambi will crow to the gods; and a third cock will raise the dead. The sun will be devoured by the wolf Skoll, and his brother, Hati, will eat the moon, leaving the world in darkness. Earthquakes will set Fenrir the Great Wolf free, and he will open his mouth so wide that his upper jaw captures heaven and his lower jaw the Earth, and he will rampage through all the nine worlds, destroying all that lives. Great mountains will fall in on their foundations. The seas will overrun the land as the serpent Jormungandr comes ashore. (20)

Sköll and Hati were Loki’s sons and, like the wolf Garm who guarded the gates of Hel, are thought to have been Fenrir in the pre-Christian tales. The Fenrir character was later given his own story, but originally, it seems it was one great wolf who swallowed both sun and moon and may have been the guardian of the realm of death. Jörmungandr, hurled into the sea as a small snake, has since grown into the Midgard Serpent and rises from the depths, causing tidal waves while Fenrir breaks his bonds and howls at the gates of Hel, and she provides him with an army of the dead, their essence sucked from them by Nidhogg, who will follow Loki, also now free, into battle.

Loki and his crew arrive at the battlefield of Vigrid with Surtr and his other fire giants either aboard the ship Naglfar or in another. Naglfar was a ship built of the fingernails of the dead and is given in the Völuspá as piloted by Loki but elsewhere by the giant Hrymr. Surtr wields a sword brighter than the sun as they come ashore at Vigrid and are met by Odin and the other gods of Asgard along with the heroes of Valhalla and, possibly, those of Fólkvangr (though this is speculative). There is also no mention of the Valkyrie at Ragnarök, but it is assumed they would fight alongside their king, Odin, and their close associate, Freyja.

Odin is killed by Fenrir who is then killed by Odin’s son Vidarr. Thor kills Jörmungandr but succumbs to the serpent’s poison after taking only nine steps after the battle and falls dead. Loki and the god Heimdall kill each other, Freyr is killed by Surtr, Týr and Garmr wind up killing each other, and the gods Mani and Solveig are slain by Sköll and Hati. Surtr sets fire to the world with his sword and the Nine Realms fall in flames, ending the cycle of life that began with the gods’ act of creation.

Conclusion

Survivors of the cataclysm include the goddesses Frigg, Freyja, Sif, Idunn, Thor’s daughter Thrud, Thor’s sons Magni and Modi, Hermodr, Aegir, Odin’s sons Vidarr and Váli, and a few others; no survivors are given for the forces of chaos. It is assumed that Loki’s daughter Hel falls with her realm in the conflagration as no mention is made of her afterwards. Baldr, his wife the moon goddess Nanna, and Hodr are released from Hel, also suggesting that the Queen of the Dead no longer has power over her subjects. The world is reborn as described in the Völuspá:

I see the earth

Rise a second time

From out of the sea,

Waterfalls flow,

And eagles fly overhead,

Hunting for fish

Among the mountain peaks.

The Aesir meet

On Ithavoll

And regard

The bones of the Midgard-serpent,

And there they recall

The great events of Ragnarök

And Odin’s old wisdom.(Stanzas 57-58, Crawford, 15)

The gods will visit the area where Asgard’s city once stood, finding the gold game pieces they used to play with in the grass, and they will remember what was and tell stories of the heroic past for a new present. Two humans, Lif and Lifthrasir, have survived Ragnarök by hiding and now come forth to repopulate the earth and a new cycle of life is begun.

This vision of the rebirth of the world following Ragnarök includes the palace known as Gimlé – "a hall more beautiful than sunlight" – on the plains known as Ithavoll (Iðavöllr), where they first meet after the battle, which will "bear harvest without labor" in a world where "all sickness will disappear" (Völuspá, Stanzas 57-61). Modern-day scholars have noted the similarity between this tale of rebirth and the concept of a new heaven and new earth from Christianity, and some claim it is a later reimagining of an old myth that ended in death and destruction with no hope of renewal.

Scholar Daniel McCoy, for example, argues that, initially, Ragnarök was the end of all things, including the gods, as he notes that pre-Christian Norse belief does not suggest a belief in rebirth. The problem with McCoy’s claim is that all extant Norse mythology was written by Christians or those living in and influenced by a Christian society so what exactly "pre-Christian Norse beliefs" may have been is unclear.

McCoy’s claim, however, is interesting to consider as he notes that the tale of Ragnarök would have developed during a time when Christianity was "killing" the old gods and ending traditional Norse values. The world one had known was changing into something new and, initially at least, unwelcome as a foreign belief system replaced the order, traditions, and rituals one had always known. In this climate of uncertainty, the end of the world without the possibility of a rebirth would certainly have suggested itself. At the same time, pre-Christian Scandinavian and Icelandic belief seems to recognize the cyclical nature of existence – as many ancient cultures did – and it is equally possible, even probable, that they saw in Ragnarök only an end to one part of the cycle of life which rises and falls to rise again.

However Ragnarök may have been initially envisioned, this is the version that was retained because it offers hope in a world of uncertainty. This is the vision of Ragnarök currently popularized through the game God of War, the film Thor: Ragnarök, and the Norwegian TV series Ragnarök, which reimagines the gods of Asgard as teenagers battling the giants in the form of big business, pollution, and climate change. Although the TV series is ongoing, it is expected to follow the paradigm of the myth in which order triumphs over chaos and good over evil even in the darkest of times.