Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was an American essayist as well as the foremost representative of the transcendentalist movement of the early to mid-19th century. Known mostly for his essays Self-Reliance, The American Scholar, and Nature, he was also a major poet, although he did not consider himself one.

His works not only inspired writers of his own generation (e.g. Henry David Thoreau and Nathaniel Hawthorne) but also authors of the 20th century such as Theodore Dreiser, Robert Frost, and Ralph Waldo Ellison. His home in Concord, Massachusetts, became a haven for many young "like-minded New Englanders."

Early Life

Ralph Waldo Emerson was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on 25 May 1803, the second of five surviving sons; three other siblings died in childhood. When he was eight, his father, a Unitarian minister, died, leaving his family in poverty, often on the brink of starvation. These early years of poverty would foster in Emerson a streak of independence visible in his essays and poetry. To survive, his mother ran a boardinghouse but was determined that her sons would receive a good education. At the age of nine, Emerson attended the Boston Public Latin School. His years at Harvard (1817-1821) were seen as frugal, industrious, and undistinguished.

In 1825, he attended the Harvard Divinity School to study theology. The years 1826-1827 were spent outside Boston recovering from tuberculosis. With his health restored, he began preaching, and in 1829, he was ordained a Unitarian minister at Boston Second Church, but he soon realized that church life was not to his liking, especially the daily mundane duties of a minister. His contempt began to grow and become more serious. He became skeptical of Christianity, developing a faith "greater in individual moral sentiment than revealed religion" (Norton, 1104).

Tour of Europe & Lecturing

Around 1831, having read the works of the English philosopher and theologian Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), Emerson underwent an intense religious experience. In 1832, he notified the church that he had grown skeptical of the validity of the Lord's Supper and would no longer administer it. He believed that the God he had found in his consciousness had little need for dogma and rituals. He also believed that the Christ that once had moved him was not a God that had come to earth. Emerson had grown to totally reject the church's institutional life and their claims to a unique revelation. Although he had the support of members of his congregation, he resigned from his position.

The following year he left Boston and went on a tour of England and the continent, needing to recover from his young wife's death. In 1829, he married Ellen Tucker, who had died of tuberculosis 16 months later. The trip was not only an attempt to recover from Ellen's death but also a chance to come to terms with his faith. While in Europe, he listened to Coleridge speak and heard William Wordsworth (1770-1850) read his poetry. He visited the Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881), with whom he became life-long friends.

After returning from Europe, he turned his attention to a need to earn an income. He turned to lecturing across New England on ethical and cultural subjects. Over time, he would expand his circuit to include the Midwest. Mead wrote that Emerson's journals, which he had kept since college, provided him with the necessary source of material for his lectures as his prose style was very close to the oral rhetoric of his lectures. Although Ellen's legacy had provided him with a steady source of income, he continued to write.

Writing & Transcendentalism

The majority of his writing was done from 1835 to 1865. After marrying Lydia Jackson in 1836, he moved to Concord. In 1836, he published Nature, confirming his future as a prose writer. Published anonymously, Nature did not reach a wide audience. As a poet, he was considered to be one "who used the materials of other areas and disciplines to provide colors for his palette" (Essays, 21). Regarding his essays, he is said to have had a gift for "reducing a whole chapter of experiences to a single sentence" (22). Robert Mead in his Literature of the American Nation claimed that his prose was always close to that of a lecture. At the heart of Emerson's influence on the writers of his own time was a body of ideas that became known as transcendentalism. Although not a coherent philosophy, it was a state or attitude of the mind. It was a belief in the divinity of human nature. All of these ideas were held together by Emerson's "practical wisdom about life … and the optimism of his personality" (Mead, 89).

Transcendentalism has been called by some as the "flowering of the Puritan spirit" (Morison, 526) Others, however, disagree with this assessment and contend that the transcendentalists were revolting against Yankee Puritanism. Some saw transcendentalism as extreme individualism while to others it was passionate sympathy for the poor and oppressed. They spoke out for a changing mood in the young republic's spiritual life, and some so it as the "first outcry of the heart against the materialistic pressures of a business civilization" (Miller, ix). The transcendentalists championed both individualism and self-reliance as well as a belief in human intuition, which enabled the discovery of truth without reference to dogma or established authority. To Emerson and his fellow transcendentalists, God dwelt in nature and thereby in the human mind. Emerson's love of nature is most evident in his essay Nature, where he contended that nature is infused with the divine or God. It was a philosophical and literary reaction against the Unitarian intellectualism of the times. (Morris, 704)

In The American Scholar, Emerson spoke of the need for scholarly leadership to escape the "muses of Europe" and develop an American character. The essay was initially a Phi Beta Kappa commencement address at Harvard College in 1837 and has been called an "American intellectual declaration of independence." (Mead, 97) In the audience was the future essayist Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862). According to Emerson, the first thing of importance to a scholar is the influence of nature. Next, he must recognize and accept the influence of the past, its literature and arts. The best source of the past is books. Books are the best of things when used well but the worst when abused. Emerson pointed out that the scholar has duties: guiding men by showing them the facts amidst appearances. A scholar must take upon himself all the contributions of the past, the present, and the future. The scholar is the young man "now crowding to the barriers for a career, do not yet see, that if the single man plant himself indomitably on his instincts, and there abide, the huge world will come round to him" (Norton, 1147). Emerson ended by saying: "We will walk on our own feet, we will work with our own hands, we will speak with our own minds" (ibid).

The following year, Emerson was invited to return to Harvard and address the senior class of the Harvard Divinity School. Published as a pamphlet the following day, he lectured on the state of Christianity. He told the class that Christianity was lost and the ills of the church were manifest. His comments were not well received, and he was attacked for heresy. He was banned from giving any further addresses at Harvard for three decades.

In 1841, he published his Essays, which earned him a lasting reputation in both the United States and Europe. Among the essays was Self-Reliance, in which Emerson wrote about the need for an individual to be independent and non-conformist. "There is a time in every man's education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance and that imitation is suicide that he must take for himself, for better, for worse, as his portion" (Norton, 1160), He added, "Trust thyself." An individual must accept the place that "divine Providence" has found for him (ibid). Emerson claimed that society has a conspiracy against its members where the individual has to surrender his liberty and must conform. But Emerson stressed non-conformity. "Whosoever would be a man must be a non-conformist" (Norton, 1162). Society does not like a non-conformist. Emerson believed: "What I must do is all that concerns me not what the people think" (ibid). A person will always find those who think they know what is best, but one must be consistent: "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statemen and philosophers and diviners" (Norton, 1164). With self-reliance change would be necessary, changes in religion, education, pursuits, and modes of living. "Trust in yourself, never imitate ... Nothing can bring you peace but yourself. Nothing can bring you peace but the triumph of principles." (Norton, 1176)

Later Life

In the late 1840s, he began to write less and less and immersed himself in the political and social issues of the day. The two decades prior to the American Civil War (1861-65) were a period of dramatic change, and Emerson did not shy away from controversy. He protested President Martin Van Buren's (1837-1841) treatment of the Cherokee nation's forced march westward (1830-1850), a trek known as the Trail of Tears. Like Thoreau, he opposed the Mexican-American War (1846-48) and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. In a lecture in March 1854, he said: "… the Fugitive Slave Law did much to unglue the eyes of men and now the Nebraska bill leaves us staring. The Anti-Slavery Society will add new members this year" (Essays, 1216).

For the remaining years of his life, Emerson faded from public view; the years of toil and travel had taken its toll on him. In 1866, he penned Terminus. In the poem's first few lines, he speaks of old age:

It is time to be old,

To take in sail;

The god of bounds,

Who sets to seas a shore,

Came to me in his fatal rounds,

And said "No More!"(Mead, 95)

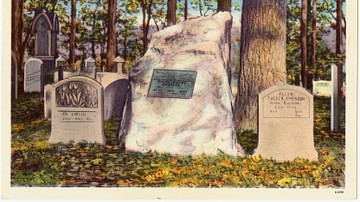

He died in Concord on 27 April 1882. He has been called the father of American literature.