The first four caliphs of the Islamic empire – Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali are referred to as Rashidun (rightly guided) Caliphs (632-661 CE) by mainstream Sunni Muslims. Their tenure started with the death of Prophet Muhammad in 632 CE, when Abu Bakr took the title of Caliph – the successor of the Prophet, although not a continuation of prophethood itself (according to the Muslims, it had ended with Muhammad), and ended with the assassination of Caliph Ali in 661 CE.

During their reign, the armies of Islam united the Arabian Peninsula under the banner of their faith and then conquered parts of the Byzantine Empire (330-1453 CE) and the whole of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) These swift and permanent conquests were halted during the reign of the last of these Rashidun Caliphs – Ali, who spent most of his reign in civil war, and whom Shia Muslims consider the only legitimate heir to Muhammad. The Rashidun Caliphs introduced an innovative administrative system, and although they failed to gain supreme authority, their system would be carried on and molded to suit the needs of time by subsequent rulers up to 1924 CE.

Caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE)

The death of Prophet Muhammad, in 632 CE, was a tragic loss for his followers, many even refused to accept that he was gone. Since Muhammad had claimed to have received divine revelations, his followers were now worried that they would no longer be guided by the divine force. More practical issues also surfaced since Muhammad had not appointed an heir to his position, nor did he have a natural heir of his own. Soon after Muhammad's death, many of the Arabian tribes declared that their pact with Muhammad was of personal nature and that they felt no obligation towards Islam (this is referred to as Ridda – apostasy in Arabic). To make matters worse, many other people had started claiming the title of prophet. However, during his lifetime, Muhammad had made it very clear to his followers that he was the last prophet of God and so these people were imposters in the eyes of the Muslims.

Abu Bakr (l. 573-634 CE), a close confidant of Muhammad and the first male convert (which earned him the nickname of Siddique – meaning trustworthy), rallied the support of the majority of the Muslim Ummah (the Sunni Muslims) and took the title of Khalifa (Caliph) – meaning successor of the Prophet. His claim was not uncontested, as a group of Muslims called Shia't Ali (party of Ali) pushed for Ali as the only legitimate candidate for the caliphate, but Abu Bakr's authority prevailed.

The apostates and false prophets posed an imminent threat to the very existence of Islam, most notable and the strongest of them was Musaylimah (d. Dec 632 CE), “the Arch Liar” as he is referred to by the Muslims. The Arabian Peninsula had fragmented once again, and if these parties were to join hands against a common enemy – Medina and Mecca, the empire of Islam would have been crushed in its cradle.

Abu Bakr showed his ability as a natural leader; he called all able-bodied faithful men to arms for Jihad (holy war – contextually). He knew that though his enemies were numerically superior, they were disunited, and he used this opportunity to its fullest. He divided the Muslim army into multiple corps and sent each to subjugate a particular part of the Arabian Peninsula – these wars became known as the Ridda Wars (632-633 CE). The most notable general of these wars was Khalid ibn al Walid (l. 585-642 CE), who defeated Musaylimah's forces, despite being heavily outnumbered, in the battle of Yamama (Dec 632 CE), where Musaylimah was killed as well.

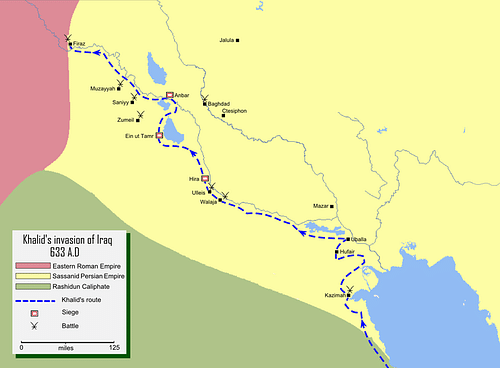

By the end of the Ridda Wars, the whole of the Arabian Peninsula was united under the banner of Islam, and for this, Abu Bakr is referred to as the “second founder of Islam” (according to historian John Joseph Saunders). Knowing that Arabs lived by the rule of retribution and that the tribes that were subjugated by force would want revenge, Abu Bakr decided to direct their energies elsewhere. He knew exactly where to go next: the neighboring lands of Syria and Iraq – which were under Byzantine and Sassanian rule respectively. Since both of these empires had exhausted themselves entirely with their constant warring, now was the perfect time to strike – Abu Bakr was in luck (although he may not have known it himself).

He sent armies to both of these provinces to extend his dominion over the Arabian tribes inhabiting them (and who had been resentful of their rulers due to high tax rates, to fund the never-ending wars between the two superpowers). Historian J. J. Saunders reports in A History of Medieval Islam how Abu Bakr instructed his corps:

In his speech to the eager volunteers who answered it, he told them (if he be truly reported) to do no harm to women, children and old people, to refrain from pillage and the destruction of crops, fruit trees, flocks and herds, and to leave in peace such Christians monks and anchorites as might be found in their cells. (43-44)

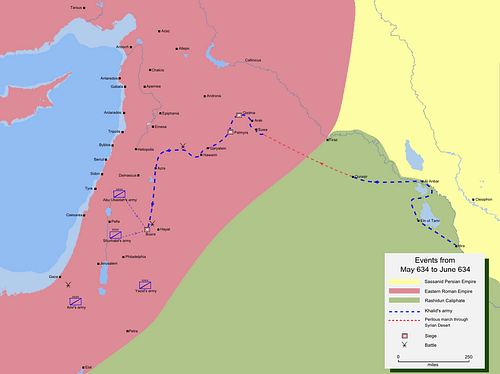

Khalid was sent to Iraq, where he was very successful, although he did kill captive soldiers – rather brutally. In the meanwhile, the campaigns in Syria were also bearing fruit. The Byzantine emperor – Heraclius (r. 610-641 CE) realized that these attacks were not mere raids and prepared for an effective counterattack (under his brother Theodore because he was himself ill). Sensing this, Abu Bakr ordered Khalid to leave Iraq and move to Syria.

Khalid then showed his military genius, he handpicked his best men and had some camels forcefully drink copious amounts of water, he then traveled all the way to Syria, through the barren, trackless, and waterless desert – he slaughtered one camel each day to quench the thirst of his men during their journey. When he entered Syria, he began raiding Byzantine territories and then used a joint Muslim force to defeat the Byzantines in the battle of Ajnadayn (634 CE) – which further strengthened their position in the region. Abu Bakr did not live long enough to enjoy these successes though, for he died of natural causes soon afterwards.

Caliph Umar (r. 634-644 CE)

Abu Bakr had received the support of many influential men; one of such men was Umar ibn Khattab (l. 584-644 CE), a senior companion of Muhammad, known for his fiery temper and his unwavering stance on justice. Abu Bakr had preferred him as his successor, and it was natural that after his death, Umar became the next caliph, he added the phrase “commander of the faithful” after his title.

Umar continued Abu Bakr's campaigns, and the year 636 CE brought two major victories for the Caliphate. The Muslim army, under Sa'ad ibn abi Waqas (l. 595-674 CE), defeated a major Sassanian counterattack in the battle of Al Qaddissiya; as an immediate result, this battle brought whole Iraq under Muslim control (while the rest of the Sassanian Empire was conquered later on). Khalid ibn al Walid's forces crushed the Byzantines at the battle of Yarmouk – technically the army was under the command of a senior man named Abu Ubaidah (l. 583-639 CE), but Khalid's expertise saved the day; the Levant was now under Rashidun control.

The city of Jerusalem was peacefully and bloodlessly surrendered to Umar, personally (he had to come to the Levant and Syria to manage domestic affairs), in 638 CE. Umar also demoted Khalid from his generalship at the morrow of his greatest achievement, and this move has been highly debated upon. Some say that Umar had personal problems with Khalid, while others press that Khalid was overly cruel (as there were many controversies against him) and Umar, being inflexible in his parameters of justice, was not ready to compromise. If the latter was the reason, Umar might have hesitated in having the rogue general executed (as he naturally would have under normal circumstances), owing to his recent achievements on the battlefield. Nevertheless, it was clear that Umar preferred Abu Ubaidah as his potential heir, but the latter died in 639 CE due to the plague that devastated Syria and the Levant.

In his ten-year reign, Umar maintained a tight grip over his empire. To this day, he is remembered as perhaps the most famous of the Rashidun Caliphs, and historian J. J. Sauders refers to him as the “real founder of the Arab empire”. He introduced the diwan – a primitive bureaucracy, which was responsible for paying soldiers their salaries and pensions. Umar also safeguarded newly conquered locals from looting by his armies by keeping armed forces separate from the rest of the population in garrison cities such as Fustat in Egypt; and Kufa and Basra in Iraq. He introduced many reforms and institutions of which the Arabs had no prior exposure to, such as the police, courts, and parliaments, he even introduced the Islamic calendar, which started from the year of the hegira – 0 AH / Zero “After Hegira”, the Prophet's migration from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE.

But of all the qualities he had, none are as praised as much as his piety and his love for justice, which earned him the title of Farooq (the one who distinguishes between right and wrong). A common story often associated with him dictates that one of his sons is said to have been accused of adultery; the witness was a woman who claimed to be the one with whom he had done so. Umar ordered his own son to be flogged, but the poor lad could not take it and died. Later on the accusation was proven wrong, Umar was crushed with grief but did not enact vengeance for his beloved son.

After Abu Ubaidah's death, he appointed Muawiya (l. 602-680 CE) as the new governor of Syria in 639 CE, the latter would in turn elevate his clan – Umayya, to the status of caliphate in 661 CE. Umar was assassinated, as an act of vengeance, by a Persian slave named Lu'lu in 634 CE, who was humiliated by the defeat of the Persians.

Caliph Uthman (r. 644-656 CE)

In his last breaths, Umar appointed a committee of six members (shura – in Arabic) to choose his successor; they narrowed the options down to two people: Uthman ibn Affan (l. 579-656 CE) and Ali ibn Abi Talib (l. 601-661 CE). Eventually, Uthman was chosen as his successor. He was from the wealthy clan of Umayya and a close friend of Muhammad (he was married to two of the Prophet's daughters), and he was also honored with the title of Ghani, "the generous", for his charitable acts.

Uthman's tenure was not devoid of military success: the whole of Egypt was consolidated, additional territories of Persia were gained, and Byzantine attempts of retaking lost territory were beaten back, ironically with the help of local populations (mostly Monophysites) who preferred being under Muslim rule as they had been severely oppressed by their former masters.

Despite all of his successes, Uthman was not as popular among the people as his predecessors had been. As the cost of constant war overwhelmed the Arabs, prices were rising and other socio-economic issues emerged (which had been kept in check by Umar), and this angered the general population. Moreover, Uthman was blamed for promoting his own kinsmen (from the Umayya clan) to important positions, and he was also charged with blasphemy (an accusation which was proven false after his demise). His declining popularity, and his refusal to use military might to crush those who started to rebel against him (which he could have easily done) on the pretext that he would not shed Muslim blood, ultimately led to his death.

The Caliph was murdered in his own house, in 656 CE, by rebel soldiers from the garrison city of Fustat (Egypt). He was reading the Quran when his assailants struck him. His wife Naila tried to save him but could not do so (she attempted to deflect the killer's sword with her bare hands and got her fingers cut). He was politically weak, but an honest and gentle man. His cousin Muawiya had offered him complete protection in Syria, but Uthman refused to leave the city of Medina where his Prophet had walked and lived.

Caliph Ali (r. 656-661 CE)

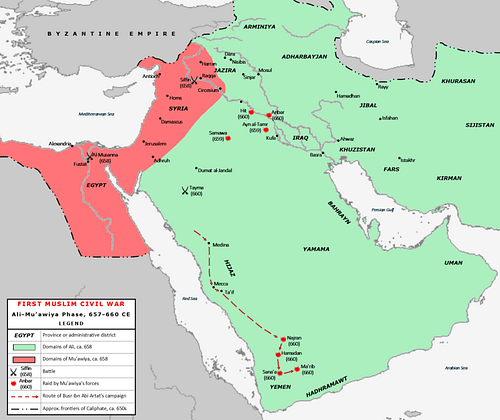

Ali, who had remained under the shadows of his seniors up to that point (advising them in the matters of the state), finally became the next caliph, but the unity of the Muslims had died with Uthman. Muawiya, now the head of the Umayyad clan, yearned for revenge, but Ali failed to provide justice to his dead predecessor, owing to increasing unrest and destabilization (Ali wished to restore order first). Not content with anything less than justice, Muawiyya alongside many other prominent Muslims declared open rebellion; the first civil war of the Islamic empire – the First Fitna (656-661 CE) thus commenced.

In 656 CE, Ali faced an army led by Aisha, the youngest wife of Prophet Muhammad, at Basra (in Iraq). Although he emerged victorious in what was later coined as the “battle of Camel” and there was little else that he could have done in that situation, his reputation was heavily stained as he was now blamed for having shed Muslim blood, something that Uthman had refused to do.

He then marched to Syria, where, in the following year, he faced Muawiya in the battle of Siffin, which ended as a stalemate, the latter continued to defy the former's authority – he had the full support of Syria, Levant, and Egypt. Ali also made the controversial move of shifting the capital from Medina to Kufa, a garrison city in modern-day Iraq. Ali was failing as a ruler; the expansion of the empire had halted and the Muslims were now at each other's throats. Though he would gain unprecedented posthumous fame due to his involvement in Shia Islamic ideology, his reputation at that point was at its lowest amongst his subjects, many of whom started to desert him.

While Ali was still ruling from Kufa, Muawiya had himself declared caliph in Jerusalem. The Islamic Empire had two caliphs at once. This changed when Ali was murdered by an extremist group called the Kharjites. The Kharjites were initially his allies, but his ultimate decision to reach a compromise with Muawiya enraged them. Ali punished the Kharjites' betrayal by attacking them with full military might, and now this extremist group was vying for vengeance. They assassinated the Caliph while he was offering prayer in congregation in 661 CE. He had not achieved much as a ruler, but both Sunni and Shia Muslims unanimously agree that Ali was a good person and a true Muslim at heart. He did make errors in judgment during his tenure which cost him a great deal, but to this day, he is venerated for his unaffected piety, proverbial wisdom, and bravery on the battlefield, and he earned the nickname of Asad Allah, "the lion of God".

The Aftermath

The Kharjites had also attempted to kill Muawiya, but he survived with only a minor injury and then established the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE). The instability of the empire under the Rashidun Caliphs was to be reversed, the Umayyads ruled with a stern hand: uprisings were crushed with brute force and rebellious provinces were kept in check by a series of ruthless but loyal governors. The Umayyads also introduced the dynastic system of rule to the Arabs and it was also under their reign that the empire reached its maximum extent.

Despite being overshadowed in political and military achievements by their successors, the Rashidun Caliphs are stilled honored as the best of the caliphs by present-day Muslims for their piety. Though their system was unstable, they laid the foundation of the Islamic Caliphates which would survive for centuries after their deaths.