The Reconquista (Reconquest) or Iberian Crusades were military campaigns largely conducted between the 11th and 13th century CE to liberate southern Portuguese and Spanish territories, then known as al-Andalus, from the Muslim Moors who had conquered and held them since the 8th century CE. With the backing of popes and attracting Christian knights from across Europe, including the main military orders, the successful campaigns ended by the final stages of the 13th century CE when only heavily fortified Granada remained in Muslim hands.

Medieval Iberia

The Muslim Moors, based in North Africa, had conquered most of the Iberian peninsula, then controlled by the Visigoths, in the early 8th century CE. By the 11th century CE, the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain were strong enough to attempt to retake some of the lost territories; an ambition greatly helped by the civil wars within the Cordoba Caliphate in 1031 CE. The five Spanish states involved were Aragon, Catalonia, Castile, León, and Navarre, while Portugal was an independent state from the 1140s CE. As these states battled the Muslims and, occasionally each other, Spain became a complex web of small kingdoms, including those set up by independent adventurers who took advantage of the political turmoil for their own ends. The most famous such figure was Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, El Cid (c. 1043-1099 CE), who eventually established his own short-lived kingdom based at Valencia in 1094 CE. The melting pot was made a little thicker with the arrival of a new group on the Muslim side, the Almoravids, an austere fundamentalist sect based in Morocco who began to extend their interest to Spain in the 1080s CE (Tyerman, 13).

The process of conquest would become known as the Reconquista - a somewhat spurious claim to 'reconquer' what the Visigoths had lost 400 years before - and it met its first major success when King Alfonso VI of Léon and Castile captured Toledo, once the capital of Christian Spain, in 1085 CE. Pope Urban II (r. 1088-1099 CE) was also a strong supporter of the reconquest idea, as the historian J. Phillips here notes: "Spiritual rewards were offered for the Iberian Peninsula in 1096 and full equality with the Holy Land probably emerged by 1114 or, at the latest, 1123" (203). Still, it is perhaps important to note that the Reconquista was different from the crusades in the Holy Land in one crucial aspect, as here expressed by the historian C. Tyreman:

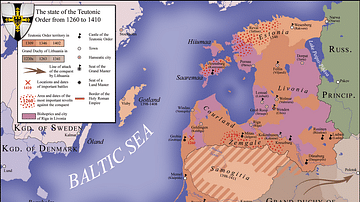

In Spain and the Baltic, political expansion and settlement drove the crusades, not as in the Near East, vice versa…In Spain, conflict between Muslims and Christian rulers long predated the arrival of crusade indulgences (652).

For this reason, it remains a matter of debate amongst historians as to when exactly the conflicts in Spain became religiously motivated crusades. In addition, cash rewards in the form of booty and forced tribute (parias) were often a far greater motivation than heavenly ones, especially in the form of gold, which the Muslims themselves acquired in huge quantities from Africa's Gold Coast.

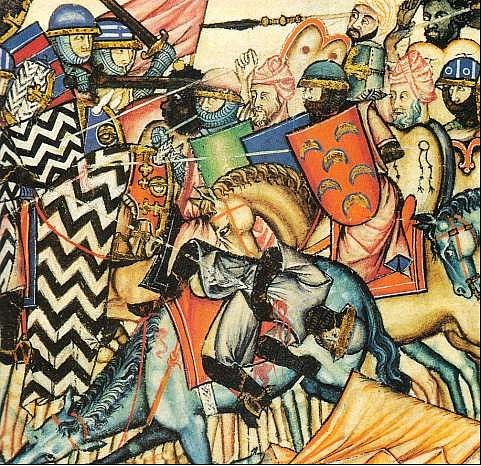

Not all campaigns in Spain were crusades, but those that were backed by the popes benefitted from the full works of mass preaching to find recruits, the raising of church taxes to fund armies, the bearing of crosses on the battlefield, and the promise of a direct route to heaven for those who gave their lives to the cause.

The Military Orders

Alfonso I of Aragon (r. 1104-1134 CE) gave huge estates (in fact most of his kingdom as he had no heir) to the Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar, both military orders of professional warrior-monks who would make themselves indispensable to the defence of the Crusader States in the Middle East. The lure, although later reduced by Spanish nobles, eventually worked, and both orders would commit knights to the Reconquista; the Templars in 1143 CE and the Hospitallers in 1148 CE. In addition, the Iberian peninsula would see the formation of its own local military orders, starting with the Order of Calatrava in 1158 CE, the knights of which famously wore black armour. The 1170s CE proved to be a busier decade for new military orders with the formation of the Order of Santiago (1170 CE), Montjoy in Aragon (1173 CE), Alcantara (1176 CE) and, in Portugal, the Order of Evora (c. 1178 CE). The big advantage of these local orders was that they did not need to send a third of their revenue to a headquarters in the Middle East like the Templars and Hospitallers. A great deal more warriors would soon be on their way to help the Christian Spanish rulers, too, as the riches on offer in southern Spain attracted professional adventurers from other parts of Europe but especially northern France and Norman Sicily.

The Second Crusade & Siege of Lisbon

The Second Crusade (1147-1149 CE) was primarily concerned with recapturing Edessa in Upper Mesopotamia, but it did have additional objectives in Iberia and the Baltic, with both these campaigns also being backed by Pope Eugenius III (r. 1145-1153 CE). The Papacy had already backed crusades to the Iberian peninsula in 1113-14 CE, 1117-18 CE and 1123 CE. The 1147 CE campaign was to be even bigger and better. The Second Crusaders who were to sail from Europe to the Middle East had to delay their departure in order for the armies travelling there by land to make their slow progress to the Levant. The sea route was much quicker, and so it was advantageous to put these soldiers to good use for Christendom in the meantime. A fleet of some 160-200 Genoese ships packed with crusaders sailed for Lisbon to assist King Alfonso Henriques of Portugal (r. 1139-1185 CE) capture that city from the Muslims. On arrival, a textbook siege began on 28 June 1147 CE and, with massive siege towers and catapults reportedly firing up to 500 stones each hour, it was ultimately successful, the city falling on 24 October 1147 CE.

Some crusaders successfully continued the war against the Muslims in Iberia, notably capturing Almeria in southern Spain (17 October 1147 CE) guided by King Alfonso VII of León and Castille (r. 1126-1157 CE) and aided by the Genoese who were promised one-third of the city. Tortosa in eastern Spain was next to fall on 30 December 1148 CE, this time directed by the Count of Barcelona but again with Genoese aid (for the same prize percentage, too). An attack on Jaén in southern Spain in 1148 CE, though, was a failure.

Christian Victory

When the idea of liberating the Iberian peninsula received the backing of Pope Innocent III (r. 1198-1216 CE) in 1212 CE, it was a timely boost to the Spanish kings who had suffered a heavy defeat at the Battle of Alarcos in 1195 CE. The Christians in Spain were suffering from a lack of unity, too. King Alfonso IX of Léon (r. 1188-1230 CE) had made an alliance with the Muslims, but his strategy brought excommunication from Pope Celestine III (r. 1191-1198 CE), and the even more unusual step of granting any Christian who fought the king a remission of sins. Consequently, Christians were now fighting fellow Christians. There was, in fact, a long tradition of alliances between Muslim and Christian statelets in Spain, trade and economics often superseding differences in religion, and there was certainly not the widespread demonization of the Muslim enemy as seen in the Middle East.

Victory at Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 CE by a coalition of three Spanish kings dealt them a blow from which they would not recover. There followed a series of further gains such as the capture of Cordoba in 1236 CE, Valencia in 1238 CE, and Seville after a long siege in 1248 CE. By the mid-13th century CE, only Granada remained in Muslim hands, the Emirate forced to pay tribute for its continued existence (which lasted until 1492 CE). No serious attempt was made to invade Muslim territory in North Africa so that reconquest never became conquest, although there would later be sporadic attacks on the Moroccan coast, notably Tangiers in 1437 CE and Arzila in 1471 CE.

Legacy

Few Muslims were converted to Christianity in the reconquered territories of Iberia, and most were permitted to remain and practise their religion as a protected minority, in effect, reversing the status of Muslims and Christians of the past few centuries. Christians were encouraged to migrate southwards, Arab place names were replaced and many mosques were, naturally, converted to churches, but some remained and Muslim calls to prayer could be heard in many Spanish cities thereafter. The Christian states in Spain became mutually suspicious of each others' intentions with everyone fearing the dominant kingdom of Castile was intent on taking over its rivals. It also proved far from easy for the new states to control their new domains and especially the new class of magnates who prospered there. This may explain why many local military orders were nationalised by the Castilian crown in the second half of the 15th century CE.

Longer-lasting effects of the crusades in Spain included the fostering of an image of Christians as specially favoured to rule, and the idea would persist for many centuries thereafter in the institutions of Spanish government and fuel the religious intolerance that would mark the region in the 15th and 16th century CE. The ideology of the Reconquista and spread of Christianity through violence would also be applied to the Spanish and Portuguese conquests of the New World following Christopher Columbus' voyage of 1492 CE.