The Reign of Terror, or simply the Terror (la Terreur), was a climactic period of state-sanctioned violence during the French Revolution (1789-99), which saw the public executions and mass killings of thousands of counter-revolutionary 'suspects' between September 1793 and July 1794. The Terror was organized by the twelve-man Committee of Public Safety, which exercised almost dictatorial control over France.

The Terror was the culmination of years of fear and paranoia, feelings which had long existed as undercurrents to the Revolution. In the autumn of 1793, as the Revolution fractured and the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797) spiraled out of control, the National Convention deemed it necessary to implement Terror as the order of the day so that it could root out counter-revolutionary spies and conspirators. This led to the enactment of the Law of Suspects, which allowed for the arrests of between 300,000 and half a million citizens nationwide. 16,594 of these 'suspects' were formally executed after a trial, while around 10,000 died in prison, and thousands more were killed in various massacres staged across France. It is estimated that the total death toll during the ten-month Reign of Terror rests anywhere between 30-50,000.

The Law of 22 Prairial (June 1794) led to a marked acceleration of killings, a month-long period known as the Great Terror, which ended only with the fall of Maximilien Robespierre on 9 Thermidor Year II (27 July 1794). The subsequent period, known as the Thermidorian Reaction, put an end to the Terror and to Jacobin dominance.

Origins of Terror

The Reign of Terror was born out of an impulse for revolutionary self-preservation, conceived by a paranoid Revolution that saw enemies everywhere. Certainly, feelings of paranoia and dread were nothing new in 1793, as the specter of Terror had been present since the Revolution's earliest days, always lurking in the shadows. Terror reared its head on 22 July 1789 when fear of an aristocratic plot to starve the people led a Paris mob to brutally murder royal minister Joseph Foullon and his son-in-law. That same summer saw the Great Fear, in which whispers of counter-revolutionary dealings by aristocrats caused panicked peasants to raid the châteaux of their seigneurial lords.

As the Revolution became increasingly divided and as France went to war with most of Europe, hysteria and apprehension became more commonplace. Such feelings were exacerbated by the rapid depreciation of the assignat currency, and the continued scarcity of affordable bread. By the summer of 1793, ordinary French citizens were no less destitute, starving, or unemployed than they had been at the start of the Revolution. Moreover, inflammatory journalists and politicians kept them on their toes, insisting that their poverty and hunger was the fault of counter-revolutionary agents or foreign conspirators.

Such rhetoric was constantly reinforced by the actions of the Revolution's enemies; for instance, the Brunswick Manifesto, which threatened the complete destruction of Paris by a Prussian army, proved that the people's liberty was in grave danger. These thoughts led to bloody moments of mass hysteria, such as the September Massacres of 1792, in which Paris mobs brutally slaughtered over a thousand 'counter-revolutionaries' and priests. By the summer of 1793, counter-revolutionaries were seemingly everywhere; brutal civil wars such as the War in the Vendée and the federalist revolts, as well as the assassination of Marat on 13 July, strengthened the notion that the Republic was under attack from within, that France's most dangerous enemies were French themselves.

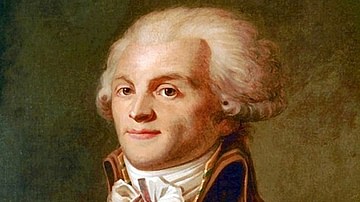

Yet, if the Terror was fueled by the fears of the people, it was ignited by their leaders' ideologies. At the heart of the terror was the quasi-dictatorial Committee of Public Safety, which itself was dominated by Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794), the idealist Jacobin leader nicknamed "the Incorruptible" for the steadfastness of his beliefs. Robespierre and his followers believed firmly that the Revolution's end goal was to obtain a republic governed virtuously by the general will. But there was a pressing danger that if certain bad actors were left to their devices, the general will would be corrupted and the Republic would fail. To prevent this, the Robespierrists were intent on weeding out potential counter-revolutionaries and traitors. Therefore, a genuine Republic could not exist without a foundation of Terror, for in Robespierre's own words, "terror without virtue is fatal, virtue without terror is impotent" (Robespierre, 21).

Terror as the Order of the Day

On 2 June 1793, the moderate Girondin political faction was purged from the National Convention, the Republic's legislative assembly. This left ultimate political power with the extremist Mountain faction, which had long dominated the politics of the Paris Jacobin Club and its affiliate clubs, boasting over 500,000 members nationwide. The Mountain spent the summer of 1793 pursuing its leftist agenda. It finally abolished colonial slavery and drafted a new constitution that promised to be more democratic than any contemporary equivalent, offering universal male suffrage.

Yet as the Mountain celebrated its victories, the French Republic was in danger. The fall of the Girondins had resulted in the eruption of federalist revolts in key French cities, while on the frontier, Coalition armies had forced the French on the defensive. Meanwhile, the assignat continued to plummet in value. This instability caused a general strike amongst the sans-culottes, or revolutionary working classes, of Paris, who were then convinced by the 'ultra-radical' journalist Jacques-René Hébert to march on the Convention on 5 September. The sans-culottes demanded increased wages, affordable bread, and the creation of a revolutionary army to protect them and their newfound liberties.

While Robespierre squirmed beneath the sans-culottes' demands, viewing it as a potential coup by his ultra-radical enemies, his colleague on the Committee of Public Safety, Bertrand Barère, managed to turn the situation to their advantage. Barère told the sans-culottes that recent food shortages were the work of foreign spies and conspirators, who the Committee was working tirelessly to unmask. If the Convention moved to make terror the order of the day, and if the proposed revolutionary army was placed under the Committee's direct supervision, Barère promised to deliver the blood of the enemies of the people, specifically naming Marie Antoinette and Jacques-Pierre Brissot. This seemed to satisfy the crowds, who promptly went home.

On 17 September, the infamous Law of Suspects was enacted, allowing for the arrests of anyone who "by their conduct, their contacts, their words or their writings showed themselves to be supporters of tyranny, or federalism, or to be enemies of liberty" (Doyle, 251). It was an ambiguous definition, which in practice could be applied to just about anyone. On 29 September, the Law of the General Maximum put price controls on numerous goods, to make food more affordable. On 10 October, the young Louis-Antoine Saint-Just, a member of the Committee, proposed that France's government should remain "revolutionary until the peace" (Davidson, 188). Finally, in December, the Law of 14 Frimaire further centralized power under the Committee, cementing its status as the de facto government of France. The new Jacobin constitution was never implemented, as doing so would have required new elections; instead, it was placed reverently in a cedar ark, to be removed when the time was right, when all France's enemies had been eliminated. That time would never come.

Tools of Terror

At the top of the hierarchy of Terror sat the Committee of Public Safety. Initially created in April 1793 to oversee various government functions, the Committee was supposed to be subservient to the National Convention, which theoretically could change the Committee's membership at will. The Committee quickly eclipsed the Convention in power, however, and the twelve men who sat on it in September 1793 retained their positions permanently until the Terror ended (with the exception of Hérault de Séchelles, guillotined in April 1794).

Beneath the Committee of Public Safety were various local committees of surveillance, tasked with unmasking and arresting all 'suspects' within their jurisdictions. What defined a suspect was left to the discretion of each surveillance committee, but people could be denounced for possessing royalist or Catholic sympathies, hoarding goods, or for something as simple as addressing neighbors as 'monsieur' rather than as 'citizen'. Once denounced by a committee, a suspect would be hauled off to prison; if exceptionally unfortunate, he or she would be brought before the dreaded Revolutionary Tribunal, where the stakes were life and death. The Tribunal included 16 magistrates, a 60-person jury, and a public prosecutor, all appointed by the Convention. No trial was allowed to last more than 3 days, and only one of two verdicts could possibly be rendered: acquittal or execution. As the Terror continued to intensify, acquittals became less common.

Finally, there was the revolutionary army, which acted as the arm of the Terror and brought revolutionary 'justice' to the countryside. The army was often accompanied by Jacobin representatives-on-mission who were authorized to hold impromptu trials or courts martial on the spot.

Days of Blood: October 1793-May 1794

With the Committee of Public Safety in power, and the tools of Terror organized, the heads began to fall. The first victims were the nobles of the old regime; the trial and execution of Marie Antoinette on 16 October 1793 was followed by the death of the hapless Duke of Orléans, whose adoption of the revolutionary name Philippe Égalité did nothing to save him from the scaffold. Madame Elizabeth, sister to the late king Louis XVI of France, was executed later in May 1794. After the nobles came the deaths of military leaders accused of 'defeatism' or cowardice; Comte de Custine was executed for retreating from the Rhineland while General Jean-Nicolas Houchard, who had defeated the British at the Battle of Hondschoote, still lost his head for failing to follow up his victory.

Next came the executions of former leaders who had tried and failed to take control of the Revolution. Some of the most prominent Girondin leaders, including Brissot, Pierre Vergniaud, and Madame Roland were executed in late October and early November; the Girondins who had escaped Paris were hunted down and killed after the failure of the federalist revolts. Then it was the turn of the Feuillants, the old constitutional monarchist faction; Antoine Barnave was beheaded on 29 November while his colleague, Jean Sylvain Bailly, was executed on the site of the Champ de Mars Massacre, which he had been blamed for. Other prominent victims included the celebrated chemist Antoine Lavoisier, feminist playwright Olympe de Gouges, and Lamoignon de Malesherbes, who had defended Louis XVI at his trial.

As the Terror wore on, Robespierre and his allies consolidated their position by disposing of their remaining rivals. To the political left of the Robespierrists were the Hébertists, who promoted policies of dechristianization and wished to further intensify the Terror. Unsettled by the growing influence of Jacques-René Hébert, Robespierre decided to strike first. After shutting down Hébert's famous newspaper, Le Père Duchesne, Robespierre had Hébert and his followers arrested. He ensured that the Hébertists were tried alongside a group accused of conspiring in a 'foreign plot', to minimize the chance of acquittal. Hébert and his allies were executed on 24 March 1794. The executioners amused the crowd by stopping the fall of the blade inches above the wailing Hébert's neck several times before finally dispatching him.

Next, the Robespierrists went after their enemies to their political right, a group known as the Indulgents, led by Georges Danton. Disturbed by the Terror, the Indulgents sought clemency for those implicated under the Law of Suspects and desired an end to the French Revolutionary Wars. Disturbed by his own role in bringing about the Terror, journalist Camille Desmoulins published a new pamphlet, Le Vieux Cordelier, which attacked the Robespierrist regime and urged an immediate end to the Terror. It was immensely popular, selling over 100,000 copies before the Committee of Public Safety had it shut down.

The Indulgents, including Danton, Desmoulins, and Fabre d'Églantine, father of the French Republican calendar, were arrested on the night of 29 March 1794. Out of the twelve members of the Committee, only Robert Lindet refused to sign their death warrants, stating, "I am here to save the citizens, not to kill patriots" (Davidson, 216). On 5 April, the Indulgents went to the guillotine; on the scaffold, Danton told the executioner, "Show my head to the people. It will be worth seeing" (ibid).

The Terror Outside Paris

Alongside the historically notable victims of the Terror, hundreds of thousands of nameless, everyday citizens were arrested as suspects. Tens of thousands were sent to their graves. Across France, 16,594 people were fed to the guillotine, 2,625 of whom were executed in Paris alone. This number does not include the roughly 10,000 people who died in prison, nor the tens of thousands who were killed in the various mass executions carried out without trial.

In the winter of 1793-94, somewhere between 1,800 and 4,800 people were drowned in the freezing Loire River during the drownings at Nantes. Following the Revolt of Lyon, close to 2,000 federalist rebels were clumped together and executed by a cannon firing into them at point-blank range. Most deadly of all were the 'infernal columns' of French Republican soldiers who traversed the rebellious Vendée region, indiscriminately killing and burning whoever and whatever they came across. With all this considered, somewhere around 50,000 people may have died during the Terror, though the true number is impossible to know.

Terror & Religion

Under the influence of the Hébertists, the Terror saw an increase in programs of dechristianization during the French Revolution. In October 1793, the National Convention approved a new French Republican calendar, which retroactively began on 22 September 1792; the implication here was that it was the birth of the French Republic, not the birth of Jesus Christ, that was the defining moment in human history. By November, the Hébertists were promoting the atheistic Cult of Reason, a movement that had arisen in Paris and mocked the superstitions of Christianity. Across France, churches were either rededicated to Reason or vandalized, and Catholic priests were subjected to ridicule and forced marriages. On 7 November, the Bishop of Paris was humiliatingly forced to publicly renounce his faith, declaring himself to be "a priest…that is to say a charlatan" (Schama, 778). Three days later, a grand Festival of Reason was celebrated at the cathedral of Notre-Dame, rededicated as the Temple of Reason. The cult was popular amongst the sans-culottes and was described by Anacharsis Cloots to worship "one God only: the people" (Carlyle, 375).

Robespierre was sickened by the Cult of Reason, which rejected any divinity. While Robespierre had no love for Catholicism, he detested atheism, believing that belief in a higher power was essential for social order. Often, he would quote Voltaire: "If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him" (Scurr, 294). And so, after the executions of the Hébertists, Robespierre did invent a god, in the form of his Cult of the Supreme Being. Robespierre's cult, which acknowledged the existence of a god and the immortality of the human soul, was meant to create a kind of civic-minded public virtue. However, Robespierre's detractors believed that he himself aspired to divinity; now possessing the powers of a dictator, it seemed that Robespierre wished for those of a god. Such rumors were strengthened on 8 June 1794, when an artificial hill was constructed on the Champ de Mars for the Festival of the Supreme Being, in which Robespierre himself played the central role.

Great Terror & Thermidor: June-July 1794

The Terror did not reach its peak until June 1794, with the law of 22 Prairial (10 June). As the prisons of Paris had become full, the law, proposed by Committee of Public Safety member Georges Couthon, was meant to accelerate the judicial process. It eliminated the investigation phase of a trial, meaning that citizens could now be brought to trial simply by being denounced, with no other evidence. The law deprived the accused of their right to an attorney and eliminated the cross-examination of witnesses. Unsurprisingly, this led to a dramatic increase in executions; from 10 June to 27 July, around 1,400 cases brought before the Paris Revolutionary Tribunal ended in execution. This final, climactic month of mass executions became known to history as the Great Terror.

During this time, more people began to question the basic premise of the Terror. The civil wars had mostly been repressed, and the tide of the War of the First Coalition had turned in France's favor following the decisive victory at the Battle of Fleurus. Yet even as the danger to France's Republic lessened, the Terror continued to intensify. Now at the height of his power, Robespierre continued to justify the Terror by announcing that he possessed lists of France's enemies, many of whom were members of the Convention. He refused to reveal the names of the traitors, promising to uncover them when the time was right.

This was the last straw, as the Convention turned against Robespierre, naming him an outlaw. He was arrested on the night of 9 Thermidor (27 July), his jaw shattered by either a self-inflicted pistol shot or by one of the gendarmes sent to apprehend him. The next day, Robespierre was guillotined along with 21 of his supporters, including Saint-Just, Couthon, Francois Hanriot, and his brother Augustin. In the following months, scores of other Jacobin leaders would also be guillotined. The fall of Robespierre led to an end to the Terror and a sharp decline in Jacobin influence.