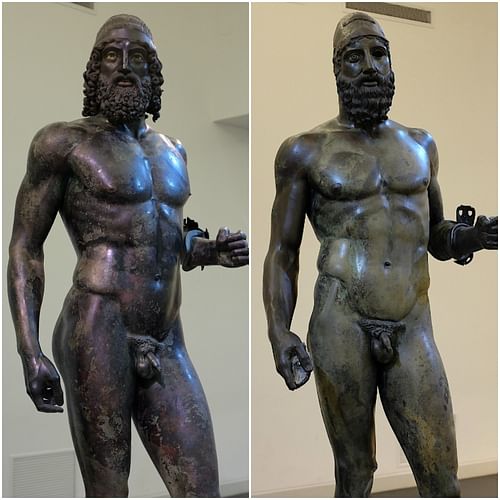

The Riace Bronzes, also known as the Riace Warriors, are a pair of bronze statues most likely sculpted in Greece in the mid-5th century BCE and rescued from the Ionian Sea near Riace Marina, Italy in 1972 CE. Slightly larger than life-size, the nude male figures represent two warriors, one older than the other, and they are considered masterpieces of Classical Greek sculpture. Restored and protected from future corrosion, they stand magnificent in their own environmentally-controlled room within the National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria in southern Italy.

Discovery & Restoration

The two bronzes were miraculously discovered in the Ionian Sea off the coast of Riace Marina in southern Italy on 16 August 1972 CE. The discoverer was Stefano Mariottini, who spotted them while diving a mere 200 metres (656 ft) from the shore. Lying at a depth of just 8 metres (26 ft), Mariottini noticed an arm sticking up from the sandy seabed and, digging down to investigate, he saw that not only did it belong to a large statue but there was a second figure buried close by. Within five days, the authorities were notified and a police diving team supervised by archaeologists raised the two figures using air-inflated balloons. Further investigation of the site in 1972 and 1981 CE revealed 28 lead rings - possibly used as part of a ship's sail - and a fragment of a ship's keel containing two bronze linchpins. These artefacts likely belong to the Roman period or later. Also discovered was a fragment of the handles of one of the figure's shield. It may be that the statues sunk while the wreckage from the light ship in which they would have been transported was dispersed by the sea. Alternatively, the statues may have been jettisoned overboard to make the vessel more seaworthy during a storm.

Before going on public display, the figures underwent a laborious process of restoration in Florence, which took five years. Sand and debris were removed from their interiors and their surfaces relieved of encrustations built up over the centuries on the seafloor. The figures were restored again from 1992-5 CE and 2009-11 CE. The statues, now standing on anti-seismic marble plinths in a climatically-controlled room of their own, are on permanent display at the National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria, Italy, where they have become the poster boys of southern Italy, silent ambassadors for the region's cultural heritage and identity.

Dating & Manufacture

The statues have been dated to between 460 and 450 BCE. Although there are differences in execution of style between the figures, there are also enough similarities for renowned Greek sculpture expert John Boardman to consider them probably contemporary. Other scholars suggest there may be up to 50 years time difference in their creation, while still others even suggest they date to the early Roman period. They may have been sculpted by different artists at different workshops or by different artists at the same workshop. The sculptor(s) are not known, even if many have been tempted to attribute the figures to such admired Greek sculptors as Phidias or Myron. Analysis of the materials of the statues in 1998 CE and 2006 CE suggest a link to either Attica or Argos.

The figures are now inseparable but they may have been selected and transported together simply because they looked similar rather than that they came from the same place of production. Certainly, the attachments on the feet of both statues indicate they had already been standing on plinths prior to transportation, strongly suggesting they were not shipped directly from whatever workshop they were made in. A likely date of their transportation would be the 1st to 2nd century BCE when the Romans looted large quantities of Greek artworks and transported them to Italy. Further, the coast of Calabria was on the favoured sea route between Greece and Italy. However, those who prefer a later date for their loss in the sea suggest that, after standing a few centuries in Italy, they may have been on their way from Rome to Constantinople sometime in the 4th century CE.

More certain than their provenance is their method of manufacture. The two figures are made of cast bronze. This metal was the favourite of Greek artists but, because it was always in demand for reuse in later periods, very few complete sculptures (no more than 12) have survived. Very often at ancient Greek sites, we see merely rows of bare stone plinths, silent witnesses to art's loss. The most common production of bronze statues used the lost-wax technique. This involved making a core (which could be made up of composite pieces as is the case with this pair of bronzes) almost the size of the desired figure or a part of a body if the bronze sculpture was to be assembled later. The core was then coated in wax and the details sculpted. The whole was then covered in clay fixed to the core at certain points using iron rods. The wax was then melted out and molten bronze poured into the space once occupied by the wax. When set, the clay was removed and the metal surface finished off by scraping, fine engraving and polishing.

Statue A

Both statues sport beards and both strike a very similar pose. They both have both their feet resting on the ground with the left leg slightly forward of the right, and both are turning ever so slightly to the right. The arms hang at the sides with the left arm bent and holding a shield (neither of which have survived except the handles of Statue A's). In their right arms they held, in an almost vertical position, perhaps a lance or spear (which have not survived either but the lead fixture and corresponding grooves in the arms are still clearly visible). The disappearance of the shield and weapons may be due to their probable separation from the figures while they were being transported.

Known a little unimaginatively as Statue A, the younger (in appearance) of the nude male figures stands 2.05 m (6.73 ft.) tall. The thickness of the bronze is on average 8.5 mm (0.33 inch). Statue A has a long beard - much more deeply carved than Statue B's - and he wears a band around his head, probably meant to represent the woollen band that warriors wore to cushion their bronze helmets. That the statue originally had a helmet is strongly suggested by the presence of a linchpin hole at the crown and triangular protrusions at the side of the head. However, some scholars point out that the sculpted detail of the hair, which would not have been seen under a helmet, suggests the warrior may not have worn one at all. The hole on the crown may have been for a meniskos (a pointed disk designed to keep birds from perching on the figure's head). It may also be that a helmet was added later to the sculpture, as is the case with some of the side parts of the beard.

Details of both statues are picked out using materials other than bronze. Calcite was used to make the eyes with the pupils rendered using a glass paste and tear ducts using rose-coloured stone. The nipples, eyelashes and open lips were made using copper. In the case of Statue A, the front rows of teeth are visible and made using a single strip of silver.

Statue B

Statue B is 1.98 m (6.5 ft) tall, and the bronze is a little thinner on average than in Statue A, measuring around 7.5 mm (0.3 inches). Statue B wears a Corinthian helmet pushed to the back of his head and held in place by a bronze linchpin. There are indications that the figure wears a cap under the helmet, a common habit of Greek military commanders. Statue B seems to represent an older warrior than Statue A, he seems more relaxed, perhaps wearier and wiser than the self-confident and strutting younger figure. Unfortunately, Statue B's left eye is missing its calcite and this, along with his somewhat elongated head and flatter beard, makes him seem a little less handsome than his more dashing partner. He has, in keeping with his greater battle experience, also suffered other misfortunes as his right arm and lower left forearm were restored in antiquity, as chemical analysis of the metal reveals. The upper left arm was also reworked and reattached in antiquity, probably in late Hellenistic or Roman times as indicated by the reattaching alloy used.