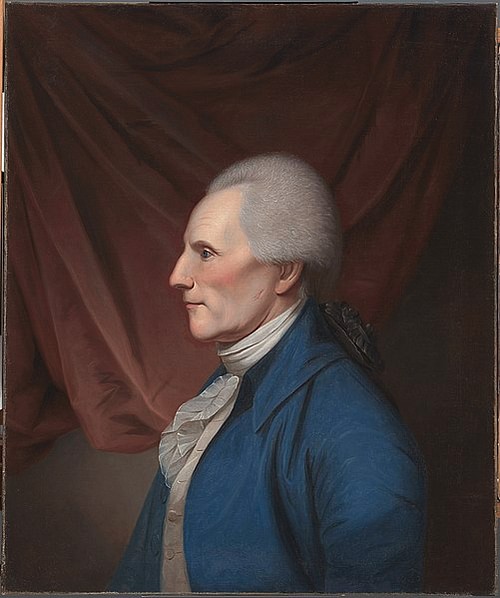

Richard Henry Lee (1732-1794) was an American politician from Virginia, who played a significant role in the American Revolution (1765-1789), particularly in the push for independence. A member of the prominent Lee family of Virginia, he served in the Second Continental Congress and, later, as a United States Senator. He is considered a Founding Father of the United States.

Family & Early Life

Richard Henry Lee was born on 20 January 1732 in Westmoreland County, Virginia, the fourth surviving child of Colonel Thomas Lee and Hannah Ludwell Lee. The Lee dynasty was one of the most prominent families in colonial Virginia; it had been founded in 1639 by Richard Lee 'The Immigrant', who had arrived in Jamestown with ambitions of becoming a tobacco planter. By his death in 1664, the first Richard Lee had established a lucrative tobacco empire and left behind a vast fortune for his eight children. Over the next several decades, the Lee family continued to grow, its members securing important positions in Virginia's colonial politics. Thomas Lee, for instance, was elected to the House of Burgesses in 1724, was appointed to the governor's council in 1733, and was acting governor of Virginia at the time of his death. He used the income generated from these offices to help finance the construction of Stratford Hall, a new residence for the sprawling Lee family.

Richard Henry Lee was born at Stratford Hall, where he spent much of his childhood. He was educated by a family tutor in the gentlemanly pursuits of horseback riding, dancing, and hunting, and he was often employed as a courier by his father to exchange correspondence with neighboring plantations. In February 1748, at the age of 16, Richard Henry was sent to Wakefield Academy in Yorkshire, England, to finish his education. Here, he fell in love with the young daughter of a prominent merchant, to whom he was soon engaged. Their budding romance became overshadowed by tragedy, when, in 1751, Richard Henry received word that both his parents had died the previous year. His eldest brother, Philip Ludwell Lee, was now the head of the family and requested that Richard Henry return to Virginia to help settle family affairs. Distraught though he was at the loss of his parents, Richard Henry refused to leave England, wishing instead to continue his courtship. Philip, perhaps believing that the girl was not a suitable match for his brother, responded by breaking the betrothal; an enraged Richard Henry still refused to go home, deciding to spite his brother's authority by embarking on a year-long tour of continental Europe.

When he finally returned to Stratford Hall in 1753, he found that his younger siblings had also gotten fed up with Philip's overbearing authority. What was worse, Philip had not yet divided their father's estate according to his will, claiming that he wanted to settle their father's debts first. Unwilling to wait, Richard Henry and the younger Lee siblings brought a lawsuit against Philip in 1754; though the suit ultimately failed, the younger Lees succeeded in transferring their guardianship to a cousin, Henry Lee, thereby freeing themselves from Philip's authority.

In the House of Burgesses

In 1756, Richard Henry Lee first entered public life when he was appointed justice of the peace for Westmoreland County. The next year, he was elected to the House of Burgesses, representing Westmoreland, where he was soon joined by two brothers, Thomas Ludwell Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee, as well as two cousins; that same year, Philip Lee was appointed to the governor's council. Thus, in a single election cycle, five Lees entered the House of Burgesses and one the governor's council, creating a powerful voting bloc that seemed poised to dominate Virginian politics. Richard Henry reconciled with Philip, with the two brothers putting aside their differences to advance family interests. They were soon able to turn the Lee family wharf at Stratford Landing into a major hub of trade on the Potomac River. Richard Henry Lee also played a pivotal role in ensuring that the Virginia militia remained well-supplied during the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

It did not take long, however, for the Lee bloc to make powerful enemies. John Robinson had served as both the speaker of the House of Burgesses and the treasurer of the colony of Virginia for over two decades; he also happened to have been a major political opponent of Richard Henry Lee's father. Hoping to knock Robinson down a peg, Lee began a campaign to separate the offices of speaker and treasurer, claiming that the combined positions gave Robinson too much power. When this effort failed, Robinson and his allies launched their own political attacks against the Lees, beginning a bitter feud that divided the House of Burgesses. The rivalry reached its apex in the early 1760s when Lee accused Robinson of embezzling funds. Robinson continued to deny the allegations until his death in 1766, when new evidence revealed that £100,000 were missing from the colonial treasury. Lee, though vindicated, earned lasting enmity from Robinson's allies, including Edmund Pendleton and Benjamin Harrison.

Chantilly-on-the-Potomac

Just as Lee's political profile grew, so too did his family. On 3 December 1757, he married 19-year-old Anne Aylett, with whom he would have two sons and two daughters. Looking to build a home for his new family, he leased 500 acres of land from his brother Philip and, in 1763, completed the construction of Chantilly, a three-story, Georgian house located on the Potomac River. Lee doted on his new home, throwing lavish dinner parties for Virginia's high society. He kept a pair of spy glasses by the window so guests could look out on the Potomac and view the Lee family tobacco ships sailing by. During these ostentatious parties, Lee would consume large amounts of alcohol, which contributed to his constant health problems. He struggled with gout for most of his adult life, which occasionally got so bad that he could not get his gout-swollen feet into shoes.

Lee loved taking advantage of the creeks on his property to hunt wild birds. In early 1768, he was on one such hunt when his rifle exploded in his hands. He ended up losing all four fingers on his left hand and thereafter wore a black silk glove to hide the injury. In December of that same year, his wife Anne died after an illness. Lee was still recovering from her death when, in August 1769, a hurricane hit Chesapeake Bay and ravaged Stratford Landing; Lee was forced to take a leave of absence from the House of Burgesses to oversee repairs and did not return until 1771. By then, he had taken a second wife, Anne Gaskins Pinckard, with whom he would have five more children.

It must also be noted that Richard Henry Lee was a slaveowner. He had inherited 40 enslaved people from his father, and at the time of his death in 1794, he owned 63. According to Lee's biographer J. Kent McGaughy, enslaved people at Chantilly likely lived in small, one-room structures and were afforded little more than was necessary for survival. Lee clearly had no qualms about owning slaves, though he did often speak out against the slave trade. He did not do so out of any ethical consideration, however, but rather because he noticed that Virginia was developing slower than other colonies that did not rely so heavily on slave labor. Like many of his fellow white Virginians, he lived in constant fear of a slave revolt and cautioned against importing too many Africans, who might rebel against their masters.

Revolutionary Politics

In the 1760s, Lee began to grow disillusioned with the British government. The Royal Proclamation of 1763, which restricted American settlement west of the Alleghany Mountains, denied Virginians access to the Ohio River Valley. The lands along the Ohio River, which had long been claimed by Virginia, were rich and fertile, perfect for the cultivation of tobacco. If Virginian planters could not access these lands, they risked losing their status as the leaders of the tobacco trade. To make matters worse, Parliament enacted the Currency Act in 1764, which disallowed the use of paper money to pay off private debts; this, too, had a negative impact on Lee's business. Combined with the 1769 hurricane that killed entire fields of tobacco crops, Lee was facing financial misfortune. He joined with firebrands like Patrick Henry to oppose Parliament's Stamp Act (1765) and Townshend Acts (1767-68), adding his voice to the chorus condemning Parliamentary taxes as unconstitutional.

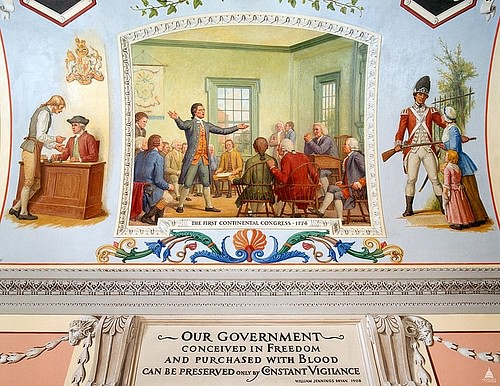

Then, in 1774, Parliament passed the so-called Intolerable Acts. Primarily intended to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party, the Intolerable Acts included a provision known as the Quebec Act, which extended the borders of the British Province of Quebec (Canada) to the Ohio River Valley. This enraged Lee; the loss of access to the Ohio Valley had been bad enough, but for Virginia to lose the territory altogether was unbearable. In September 1774, Lee attended the First Continental Congress as one of seven delegates from Virginia. He took a hardline stance against Parliamentary power, in the belief that if Parliament's authority was not reduced, the Quebec Act would never be rescinded.

Lee's fervor impressed John Adams, who referred to him as a "masterly man" (McGaughy, 109); henceforth, Lee caucused with John Adams, Samuel Adams, and Patrick Henry, the radicals who sought a reduction in Parliamentary authority. Lee worked to establish the Continental Association, an agreement to boycott all British-made goods until the Intolerable Acts were repealed, and he sponsored a motion demanding the removal of British troops from Boston. His unwavering radicalism earned him the ire of the moderate faction, which still sought reconciliation with Parliament and included his old rivals Pendleton and Harrison.

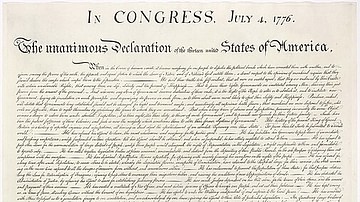

In May 1775, after the first shots of the American Revolution had been fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April), Lee returned to Philadelphia to take his seat in the Second Continental Congress. Once again, he threw his lot in with the radicals, becoming an early supporter of independence. The independence faction, known as the Adams-Lee junto, gained momentum as the war dragged on; Congress' last-ditch attempt at reconciliation, the Olive Branch Petition, failed, and the king's subsequent Proclamation of Rebellion made it clear that Britain wanted nothing less than the complete subjugation of the colonies. The popularity of Thomas Paine's seminal pamphlet, Common Sense, in early 1776 helped push public opinion in the direction of independence, allowing the Adams-Lee faction to become more vocal about its true goals. On 7 June 1776, Lee presented Congress with a motion:

These United Colonies are, and of right to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved. (Middlekauff, 331)

Lee's motion calling for independence was so fiercely debated that the Congress' president, John Hancock, ordered it be set aside until 1 July. When the time came for a vote, Lee's motion passed overwhelmingly and, on 4 July 1776, Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence. The United States was born.

Silas Deane Scandal

Despite his political successes, Lee remained deeply hated by his enemies, who began to scheme to unseat him from Congress. In early 1777, his opponents spread rumors that Lee was plotting to remove George Washington from command of the Continental Army. This was untrue, but it placed Lee in a bind; if he denied the rumors, he risked upsetting his New England allies, who had grown tired of Washington's handling of the war, but if he said nothing, he risked alienating Washington himself. Lee deftly managed to extricate himself from the situation, soothing the concerns of the New Englanders while simultaneously explaining himself to Washington.

But it was not long before Lee was embroiled in more controversy. In 1777, Congress had dispatched three commissioners to Europe to secure foreign support: these included Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia, Silas Deane of Connecticut, and Arthur Lee, Richard Henry Lee's youngest brother. Arthur wrote to Richard Henry, voicing his suspicions that Silas Deane was using his political influence to advance his own business interests. Deane came under further suspicion when a swarm of French military officers arrived in America, claiming that Deane had promised them commissions in the Continental Army. Washington, who had no room for so many foreign officers, complained to Congress which, in turn, expressed surprise, claiming that it had never given Deane the authority to promise commissions to so many officers. He was recalled and John Adams, Lee's ally, was sent to France in his place.

This caused outrage amongst Lee's enemies, who claimed that the Adams-Lee junto had orchestrated Deane's downfall in order to send one of their own to Paris. Deane himself, when he defended his actions before Congress in August 1778, laid the blame at the Lees' feet. This led to a year-long political struggle that nearly disrupted the proceedings of Congress, each side accusing the other of corruption. The rivalry climaxed at the end of 1778 when the Deane faction attempted to dismantle Virginia's claim on the Ohio territory. Lee managed to thwart this attempt, but only barely. By May 1779, Lee had had enough of these dirty politics and resigned from Congress, returning to Chantilly.

He continued to contribute to the Revolution by funding the Westmoreland County militia. In 1781, during the Siege of Yorktown, Lee organized supplies for the Continental Army and sent 200 militia under his son, Ludwell Lee, to join Washington's army; in a letter, he explained he would have gone himself had it not been for his debilitating gout. Washington expressed gratitude and had Ludwell join the staff of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

Postwar Politics

In September 1783, the Treaty of Paris brought the American Revolutionary War to an end. In June 1784, the Virginia House of Delegates appointed Lee to Congress and, the following November, he was named its president. As president of Congress, Lee spearheaded the passage of the Land Ordinance of 1785, which set up a system that would allow settlers to purchase farmland in the undeveloped west. His presidency also oversaw negotiations between John Jay, the American foreign secretary, and the Spanish foreign minister about the Americans' right to access the Mississippi River. His term as president expired on 4 November 1785, and he returned to Chantilly; he was regarded by contemporaries as one of the most effective presidents of Congress.

In 1787, the US Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia to devise a replacement for the weak Articles of Confederation. Lee, who declined to attend due to his ill health, was nevertheless concerned that the proposed Constitution contained no Bill of Rights; he proposed a list of amendments based on the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights written by his friend George Mason, that included the freedoms of speech and the press, as well as the right to jury trials. Lee's criticism of the Constitution, and preference for a weaker central government, earned him the wrath of the Federalist supporters of the Constitution. However, after the US Constitution was ratified by the states, Lee agreed to serve in the new US Senate for a four-year term. He expressed his delight when his friend George Washington won the US presidential election of 1789; he wrote a letter to the general stating that his worst fear was that Washington would refuse to serve.

Washington did indeed serve as president, with Lee's old ally John Adams as his vice president. But Adams, a staunch Federalist and supporter of a strong central government, soon butted heads with his old friend Lee, who still supported a limited federal government. Their friendship soon devolved into a bitter rivalry after Adams attacked Lee's integrity and personal honor on the Senate floor. Afterward, Lee took every opportunity to criticize Adams' conduct, at one point even attempting to get rid of the Vice President's right to cast a tie-breaking vote in the Senate. As part of his Antifederalist agenda, Lee opposed the creation of federal judiciaries, believing they would take power away from existing state courts.

Lee also opposed Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton's plan for the federal government to assume state debts to create a national line of credit; Virginia had already paid its debts, and Lee did not see why Virginians should be burdened with the debts of other states. Lee and other Virginian lawmakers eventually agreed to support Hamilton's plan, but in return, they required that the proposed national capital be built on the Potomac River. Hamilton and his allies agreed to the compromise, and in 1790, President Washington signed the Residence Act that established a site on the Potomac as the location of the future capital (which became Washington, D.C.).

Retirement & Death

At the end of his term in May 1792, Lee learned that the Virginia House of Delegates was considering electing him for a second term. He wrote them a letter, asking that his name be removed from consideration; he had, in his own words, "grown gray in the service of my country" and noted how he had "infirmities that can only be relieved by a quiet retirement" (McGaughy, 217). He returned to Chantilly to live out that quiet retirement and spent his final months improving the estate that he loved so much. His health continued to deteriorate until he died at Chantilly on 19 June 1794 at the age of 62.