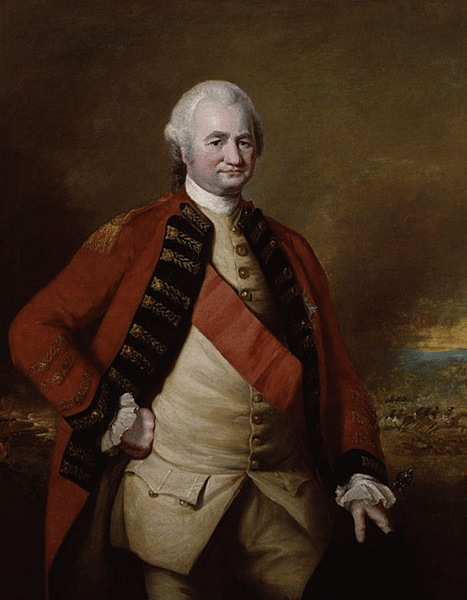

Robert Clive (1725-1774), also known as 'Clive of India' and Baron Clive of Plassey, masterminded the expansion of the East India Company in India. Best known for his victory at Plassey in Bengal in 1757, Clive's reputation suffered in his own lifetime from charges of corruption and subsequently as one of the main architects of British imperialism in India.

The East India Company

Robert Clive was born into a country gentry family at the ancestral home of Styche Hall in Shropshire, England, on 29 September 1725. His father was Richard Clive and his mother Rebecca Gaskell. He studied at Merchant Taylor's school in London from 1737 and then accounting in a specialist school in Hemel Hempstead. At just 17, Clive joined the East India Company (EIC) as a humble 'writer' or clerk in December 1742. He arrived in India in 1744 after an unusually long 15-month voyage since his ship had run aground on the coast of Brazil. It was here in India that he would fulfil his ambiguous destiny as both champion of the British Empire and utterly ruthless colonialist. The historian S. Mansingh gives the following summary of Clive's character: "sturdy, violent, self-centred, emotional, generous, courageous, and brilliant in adversity" (101).

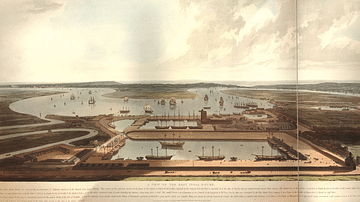

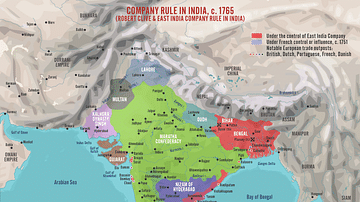

The EIC was a joint stock company founded in 1600 to become the trade representative of the British Crown everywhere east of the Cape of Good Hope. With the Dutch East India Company monopolising the spice trade in Indonesia, the EIC focussed instead on India. The early 17th century saw the company set up a trading centre at Surat in agreement with the Mughal emperor. More centres followed as the century progressed: Masulipatam (Machilipatnam) and Madras (Chennai, 1640), Hughli (1658), Calcutta (Kolkata, 1690), and Bombay (Mumbai, 1668). The EIC enjoyed a trade monopoly with India until 1813, and, as a result, it made a fortune. By the mid-18th century, the EIC was looking to expand its territories in India and, to do that, it needed to build an army and find men to lead it.

Early Career

Clive arrived in Madras in 1744 and began his duties as a Company clerk. With not much to do after work, he spent a great deal of time educating himself in the Company library. Just two years later, the French East India Company, which was particularly active in southern India, took over Madras, and Clive found himself a prisoner. Fortunately for Clive and the EIC, a monsoon storm wrecked much of the French fleet and obliged them to withdraw. Meanwhile, Clive and three colleagues escaped by disguising themselves as Indians. On reaching EIC-controlled territory again, Clive enlisted in the Company's army and, after more fighting with the French, was promoted to the rank of ensign.

Clive fought with distinction in the failed attempt to take French-controlled Pondicherry, and he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant. He was involved in two attacks on French-held Tanjore in 1749. the first operation was a failure, but the second was a success, and Clive earned the following praise from his commander Major Stringer Lawrence: "This young man's early genius surprised and engaged my attention…he behaved in courage and judgement much beyond what could be expected from his years" (Fraught, 24). Clive was again promoted, this time to become Lawrence's steward. This position made Clive responsible for supplies to Fort St. George, Madras, and as was the custom with such jobs, he was entitled to a cut of every deal. Thus began the first accumulation of Clive's legendary wealth. Not everything was positive. Clive's promotion to Captain had been rejected as the Company sought to focus on trade, not war, he suffered a severe bout of typhoid fever, and the ongoing struggles with the French were going badly.

The Siege of Arcot

In August 1751, Clive was finally made a Captain, and he led a force of 200 British soldiers and 500 sepoys (Indian soldiers) on a 65-mile (105 km) march from Madras to the desert town of Arcot, then the capital of the Carnatic region. An attack on Arcot, it was hoped, might relieve pressure on the British besieged at Trichinopoly. In this period, the British and French Companies were often fighting a proxy war through their support of local rulers and their armies. Arcot was to be just such an engagement. As it happened, by the time Clive had proceeded through a storm and arrived at Ascot, the defensive force of some 1,000 men had already fled. Now, though, Clive would have to defend Arcot against a siege.

Clive received significant reinforcements from Madras, including artillery, but he was severely outnumbered by the combined besieging army of French troops and those of Chandra Sahib, the nizam of Hyderabad. Clive now commanded only around 300 men compared to an enemy of some 7,000 and so was obliged to hold only the fort of Arcot. The desert heat was unbearable, and the fortifications were crumbling, but Clive did have plenty of food, water, and ammunition, and so he withstood the siege until a relief force could arrive. Relief did come but not in the form Clive had expected. In the turmoil of regional politics, the Marathas, who had backed a rival nizam to the French-backed candidate, sent an army of 6,000 men to Arcot. The besiegers realised they must act now or never, and they launched a final attack on the fort. Clive's men withstood the onslaught, which included shooting the enemy's war elephants and causing them to stampede on their own men. With a small British relief force now arriving and news that the Marathas were camped nearby, Chandra Sahib withdrew. Clive had withstood the 52-day siege and achieved his first major military success; it also heralded a turn of the tide against the French.

Clive followed up Arcot with another victory, this time at Arni in December 1751. The geopolitical situation was still very fluid, but the desertion of sepoys from the French to British armies was an important consequence of Clive's victories. At last, the EIC saw the benefit of investing in its military arm, and a rejuvenated army won another victory, this time at Kaveripak in February 1752. Local rulers and the Marathas now began to see that the British were the most likely of the two European powers to establish regional dominance and so gave military support to an ever-growing EIC army. A major battle and then siege was won at Trichinopoly in June 1752 where the British were led once again by Stringer Lawrence. Clive had been in charge of the artillery in the field battle, but he disobeyed orders and went in search of a French supply column, failed to find it, and was routed on his return when his camp was overrun. Clive was very nearly killed that day but escaped with a facial scar as a permanent reminder of the necessity for officers not to defy their commanders.

Return to England

In 1753, Clive hung up his sabre and returned to Company commerce in Madras. In February, he married Margaret Maskelyne and then returned to England where his first son was born, Edward, on 7 March 1754. The couple would have four more children who survived the perils of infancy.

Clive was elected MP for Mitchell in Cornwall in 1754, a hotly-disputed seat and a 'rotten borough' (one that can be bought). In 1755, Clive decided he was not yet ready for a settled life in England, and so he and Margaret returned to India. Now a lieutenant colonel in the EIC army, Clive was lined up to become the next Governor of Madras. In the meantime, Clive's brief was to use Bombay as a base from which to attack French possessions in India and their proxy, the nizam of Hyderabad. Clive took the Gheria fortress in February 1756 and returned to Madras. But it was up in Bengal where a crisis was about to explode. A new ruler of Bengal, Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah (b. 1733), took exception to the EIC presence and marched on Calcutta in June 1756. A short siege followed, and the city fell.

Black Hole of Calcutta

Clive received news of the loss of Calcutta in August. It was obvious the EIC had to respond, but calls for a punitory expedition were further fuelled by an infamous incident which lived long in the British psyche (and even longer in the English language): the terrors of the Black Hole of Calcutta. According to one survivor, John Zephaniah, he and other soldiers who had defended Calcutta were imprisoned in a single cell with two small windows. Suffering extreme heat and dehydration, only 23 men of the original 146 survived the Black Hole. Debate continues today as to the real number of prisoners involved, which may have been much lower, but the effect of the incident was to make men like Clive determined to gain revenge. The incident also became one of those dubious justifications for what the British considered their 'civilizing' presence in India, especially during the Victorian era.

Clive was duly dispatched with an army to re-establish the EIC's trading presence in Calcutta. Sailing in five ships and with an army of some 1,500 men, Clive succeeded in recapturing Calcutta in January 1757, but Siraj ud-Daulah still had a massive army, and the French were in control of Chandernagore just up the coast. Clive was determined on military action. He captured the fort of Hughli later in January, which was then destroyed by cannon fire from the EIC fleet. An attack on the nawab's army outside Calcutta was less successful and obliged Clive to retreat. Both sides became wary of the other and the heavy casualties any future confrontation would bring, but the control of Bengal was at stake. A peace treaty was agreed, but both sides knew this was but a temporary pause. In the interim, Clive could now deal with the French presence in the region. In March 1757, Clive attacked and captured Chandernagore, bringing an end to any remaining ambitions the French had in Bengal. When the Hindu Seths of Murshidabad, a dynasty of financiers worried at the demise in European trade any wider conflict would bring, withdrew their support of the now isolated nawab, Clive seized the moment.

Plassey & Riches

On 23 June 1757, Clive led his EIC forces to victory at the Battle of Plassey on the banks of the Bhagirathi river in Bengal. Clive's army consisted of 1,400 sepoys and 700 Europeans. Clive's opponent was the army of Siraj ud-Daulah. The nawab's force was well-trained and greater in size than Clive's – perhaps around 50,00 men – but they were not loyal troops or commanders. Clive had only 10 sizeable cannons at his disposal compared to the nawab’s 51 (or 53 according to Clive himself) but a major benefit was the defection of one of the nawab's generals, Mir Jafar (1691-1765).

The fighting began with the usual artillery barrage from both sides. Then a heavy downpour tipped the scales. The nawab's cannons had not been protected, but Clive's gunners had wisely used tarpaulins to keep their powder dry. When the storm ended, the nawab, probably thinking Clive's cannons were also out of action, sent in his cavalry. The British artillery then opened up again and cut down the enemy horse. At the sight of this carnage, most of the nawab's infantry began to leave the field but were pursued by Clive's reserves in a chaotic and bloody melee that involved men, camels, and panicking elephants. The battle was won with the British suffering 50 fatalities and the nawab's army over 500 dead and wounded. The nawab was captured, executed, and replaced by Mir Jafar. The vast treasury of the ex-nawab was distributed amongst the victors, as was the norm, and Clive made himself vastly richer, acquiring what today would be over $50 million dollars. A grateful Mir Jafar also gave Clive the lucrative rights to the annual rent revenues (jagir) around Calcutta.

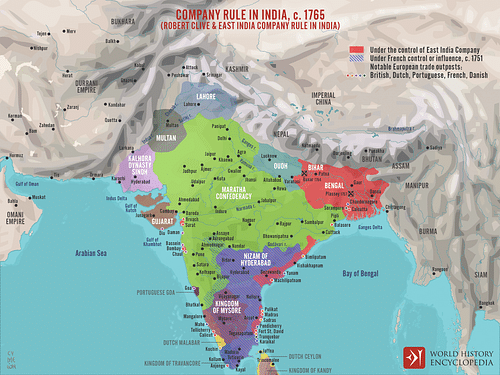

Victory at Plassey allowed the EIC to siphon off the resources of Bengal without paying the costs of administration, which were left to the nawab since the EIC had no intention of becoming a colonial power. As the beginning of the expansion of EIC territorial rule, Plassey and 1757 are often cited as the beginning of British rule in India. The battle also resulted in Clive becoming forever associated with the subcontinent and earned him the moniker 'Clive of India'. He was made the Governor of Bengal in February 1758, a post he held for two years.

Clive returned to England in July 1760. He bought properties, including Walcott Hall in Shropshire (his favourite residence), and received a seat in Parliament again, this time as the MP for Shrewsbury in 1761. In March 1762, he was given an Irish peerage and henceforth was known as Lord Clive or Baron Clive of Plassey. The Company was loath not to use Clive's talents, though, and to meet a new crisis with a new nawab, in 1764, he was appointed Governor of Bengal for a second time. Clive may well have preferred to stay in England and build his career there, but the Company was split over whether he should keep his annual Calcutta revenues, and this may have been the carrot that made him once more embark for the subcontinent. This time Margaret Clive remained in England with the children.

Clive's Reforms & the Dewani

Back in Calcutta by May 1765, one of the tasks the Company set Clive was to reduce corruption, particularly in Calcutta, and this he aimed to do by increasing regulation and reducing private trade by employees (something he himself had always benefitted from). Clive abolished two costly and dubious traditions where EIC employees received gifts as part of trade deals and drew two salaries, one for administration and another for military service (batta). Clive's attempt to reduce corruption was not successful in the longer term, and he caused great upset amongst EIC employees. Clive's reforms also applied to military personnel who were so disheartened by cuts in the batta that he had to put down the brief 'White Mutiny' of British officers. Still, Clive's reforms managed to ensure the EIC civil arm kept its control over the military arm. One of the governor's last acts in India was to establish EIC pensions for its soldiers and merchants, and funds for those invalided home or their widows.

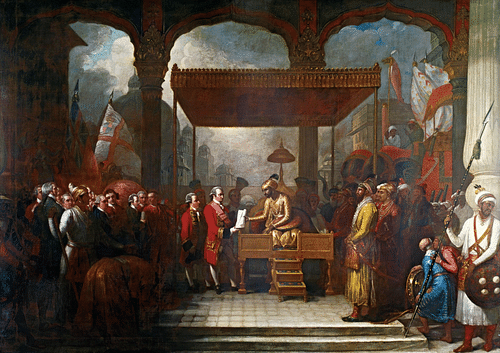

Meanwhile, the EIC's military arm continued to bring rewards. On 22 October 1764, the Battle of Buxar at Patna saw EIC forces under the command of Hector Munro defeat those of the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II commanded by Nawab Mir Kasim. Clive travelled to meet Shah Alam II, who, in return for an annual tribute from the EIC, awarded the company the right to collect land revenue (dewani) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. The deal was struck on 12 August 1765, and it ensured the Company now had vast resources to expand and protect its interests. The people of Bengal, in particular, would soon feel the full bite of the ruthlessly exploitative EIC.

Final Return to England

Clive returned to England in 1767; never a light traveller, he brought home a host of souvenirs, curiosities, and, of course, more wealth from his Calcutta annual revenues. Clive's Indian souvenirs are today housed in the Clive Museum in Powis Castle in Wales.

In 1768, he became MP for Shrewsbury again. In 1772, he was appointed to the House of Commons Select Committee on Indian Affairs, but something was amiss. Clive, although having developed the blueprint for empire-building in India and built the foundation for the British Raj, was seen by many of his compatriots as too powerful. Clive and his like were accused of enriching themselves rather than serving wider British interests. He had old enemies, too, those who had missed out on the spoils of Plassey, EIC officials who had opposed his reforms, and the press, which gleefully reminded their readers of Clive's humble origins. The affairs of the EIC came under ever-greater public scrutiny. Parliament set up an inquiry into Clive's affairs and the great riches he had plundered. Clive defended himself in the House of Commons in May 1773 with characteristic bravado: "By God, at this moment, do I stand astonished at my own moderation!" (Faught, xi). In the end, Clive was honourably acquitted with the note that he had done his country "great and meritorious services" (Watney, 215). It was the EIC itself, everyone now realised, that was to blame for the mismanagement of British interests abroad and why, just as Clive had recommended to the government, it would eventually be taken over by the state.

In his later years, Clive suffered from a lengthy series of painful illnesses that included malaria, gallstones, gout, rheumatism, and intestinal problems, none of which were helped by lengthy visits to the supposedly restorative waters of Bath or the warm climes of southern Europe. Opium was the only source of temporary relief, and even that became less and less effective. Clive committed suicide at his home in 45 Berkeley Square on 22 November 1774. The story goes he cut his own throat with a penknife, but some have speculated he died of an accidental overdose. Public statues of 'Clive of India' would be erected, but his rumoured suicide meant that he was secretly buried beneath the flooring of the church of St. Margaret of Antioch in the village of Moreton Say, Shropshire.