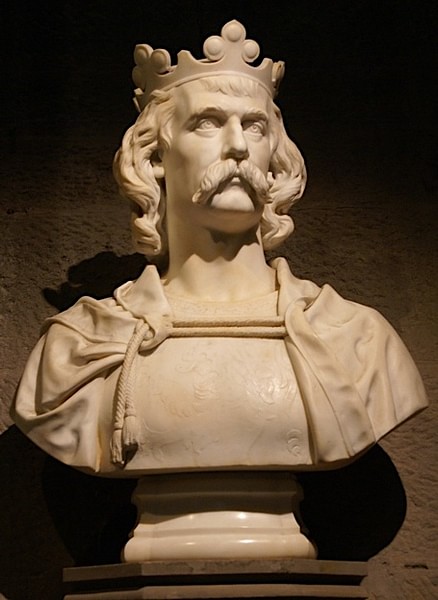

Robert I of Scotland, better known as Robert the Bruce, reigned as King of Scotland from 1306 to 1329 CE. For his role in achieving independence from England, Robert the Bruce has long been regarded as a national hero and one of Scotland's greatest ever monarchs.

Robert succeeded John Balliol (r. 1292-1296 CE) but only after a tumultuous decade of side-switching and military ups and downs against English armies led by Edward I of England (r. 1272-1307 CE) and those of rival Scottish barons. A grand victory over the English at Bannockburn in 1314 CE cemented Robert's claim to be the rightful king of Scotland and his skilful diplomacy brought recognition of Scotland's full independence both from the Pope and Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377 CE). Robert was succeeded by his son David II of Scotland (r. 1329-1371 CE).

Early Life

Robert (VIII) the Bruce was born on 11 July 1274 CE at Turnberry Castle in Ayrshire, Scotland. His father was Robert (VII) the Bruce (d. 1304 CE) and his mother was Marjorie, Countess of Carrick. The Bruce family had been the lords of Annandale since the 1120s CE, and they claimed descent from Earl David, younger brother of William I of Scotland (r. 1165-1214 CE). Robert spent a period of his youth in either the Western Isles or Ulster. As the family had estates and properties in England, so, too, he spent time in Carlisle Castle and London. In 1292 CE Robert inherited the earldom of Carrick.

Around 1295 CE Robert married Isabel of Mar (d. c. 1296 CE), daughter of Donald, earl of Mar, and then, in 1302 CE, Elizabeth de Burgh (d. 1327 CE), the daughter of Richard de Burgh, earl of Ulster. With Isabel, Robert had a daughter Marjorie (b. c. 1295 CE) and with Elizabeth, he had two daughters - Matilda and Margaret - and two sons - David (b. 1324 CE) and John (possibly the twin of David but he died as a child).

The Great Cause

When Alexander III of Scotland died (r. 1249-1286 CE) in 1286 CE and his only heir was his granddaughter who then herself died in 1290 CE, Scotland was plunged into a political crisis. The royal houses of England and Scotland had been tied via several marriages but Edward I of England went a step further and considered the Scottish king his vassal. Edward arbitrated over a host of successor candidates in a process known as the Great Cause. The English king chose John Balliol in November 1292 CE. The main challenger to Balliol had been Robert (VI) the Bruce (b. 1210 CE), the grandfather of his more famous namesake and future king. The Bruces did not accept Edward's decision and continued to press their own claim for the throne. Balliol had won because he was an even closer descendant of Earl David and, more importantly for Edward I, a more anglicised and weaker candidate, meaning he could be more easily manipulated.

As it turned out, John Balliol's reign lasted only four years as Scottish nobles tired of his ineffective resistance to the overbearing Edward and the rise in taxes imposed to pay for the English king's war with France. In late 1295 CE, a regency council of 12 discontented nobles established a new government, perhaps entirely independent of John. This council, and therefore Scotland, formally allied itself with Philip IV of France (r. 1285-1314 CE) in February 1296 CE, the first move in what became known as the 'Auld Alliance'. King John renounced his fealty to Edward I in April 1296 CE. The Bruces did not support this rebellion against Edward I's overlordship, and Robert even joined the English force that attacked Scotland in 1296 CE. Edward's emphatic response to the 'Auld Alliance' was to repeatedly attack Scotland. There was a massacre of thousands of innocents at Berwick, Edward took the key Scottish castles, and he inflicted a defeat on the Scottish army at the Battle of Dunbar on 27 April 1296 CE. Three English barons were nominated to rule Scotland, which, in effect, became a province of England. John Balliol was stripped of his title and put in the Tower of London.

War of Independence

Unfortunately for Edward I, Scotland proved rather more difficult to subdue than he anticipated. Almost immediately, rebellions sprang up. The most successful was the uprising led by William Wallace (c. 1270-1305 CE) and Sir Andrew Moray of Bothwell. The rebels won a famous victory in September 1297 CE at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. A ruling council was established consisting of Wallace, John Comyn, and then Bishop Lamberton, but the Bruces did not support this group, especially as the Comyns were supporters of the rival Balliols. At this point, the Bruces seem not to have fully backed either Wallace or Edward I but, instead, they bided their time to better see the outcome of this first stage in what has become known as the First War of Independence. By 1298 CE, though, Robert the Bruce was clearly on the Scottish side and was involved in the attack on English-held Ayr Castle. However, in 1302 CE Robert's marriage to Elizabeth, daughter of an ally of Edward I, coupled with the release of John Balliol from the Tower of London meant that Robert once again sided with the English lest Balliol's Scottish allies succeed in reinstating the ex-king.

Edward responded to the defeat at Stirling Bridge by leading his army in person and winning another encounter in July 1298 CE at the Battle of Falkirk, where 20,000 Scots were killed. Edward then sent more armies, and in 1305 CE, Wallace was captured and executed as a traitor in London. Nevertheless, Wallace had become a national hero and an example to follow for others, notably Robert the Bruce, who by 1305 CE began to have serious misgivings concerning his support for the English Crown. It now seemed highly unlikely that Edward I would ever make Robert king of Scotland. Steadily over the next year - and probably largely in secret - Robert began to work on gaining allies from key Scottish barons.

By February 1306 CE, the Scots were rallying around their new figurehead, Robert the Bruce, who denounced John Balliol as a puppet of Edward I. On 10 February, Robert or his followers assassinated John Comyn, his chief rival claimant for the throne, by stabbing him in the church of Greyfriars in Dumfries. With the definite support of the northern Scottish barons and the dubious support of others, Robert went for broke and declared himself king. Robert was inaugurated at Scone Abbey on 25 March 1306 CE. The king's position was, though, precarious indeed. There followed two defeats to an English army at Methven on 19 June and to a Scottish army led by John Macdougall of Argyll at Dalry on 11 July. Robert was obliged to flee to Rathlin Island on the coast of Ireland. The English, unable to get their hands on the king, went for the next best thing and hunted down his family. Three of Robert's brothers were executed, and his sister Mary was kept in an iron cage dangling from the walls of Roxburgh Castle, a fate she suffered for four years. Robert's wife Elizabeth was confined in a manor house at Burstwick.

When Edward I died in July 1307 CE, he was succeeded by his son Edward II of England (r. 1307-1327 CE). The new king lacked the political and military talents of his father, and he had to deal with a descent into political anarchy in his own kingdom which eventually erupted into a civil war. These developments left Scotland some breathing space. Robert was able to return to Scotland, where he and his brother Edward fought a sustained guerrilla war against English troops and Balliol supporters. By mid-1308 CE, Robert had smashed the Comyns, taken their key castles and razed them to the ground, and taken possession of Aberdeen. In the autumn of 1309 CE at the Battle of the Pass of Brander, the Macdougalls were decisively defeated, too. Now Robert offered truces to any Scots willing to follow him. Consequently, in March 1309 CE, a parliament at St. Andrews declared that the people of Scotland supported Robert the Bruce as their king. An embassy from France similarly declared that Robert was the rightful king of Scotland. Still, though, several key castles remained in English hands, and these included Berwick, Roxburgh, Edinburgh, and Stirling. Over the next four years, Robert set about getting them back, very often leading the attacks in person.

Bannockburn & Independence

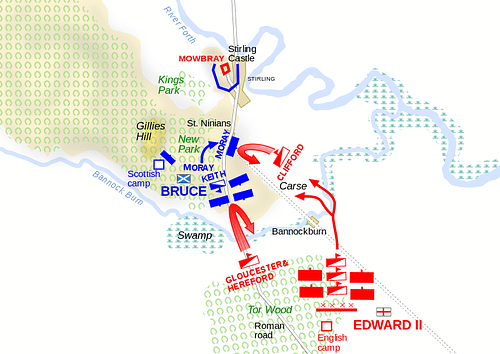

Edward II's preoccupation with his own internal troubles meant that Robert could pick off English-held castles one by one (and destroy them to prevent reuse by the enemy). He also made regular and lucrative raids into northern England seemingly at will. After an unsuccessful attack in 1311 CE, it was not until 1314 CE that Edward led an army to Scotland, the motivation being the siege of the English-held Stirling Castle. Edward's force greatly outnumbered the Scots led by Robert the Bruce (15-20,000 v. 10,000 men), but this advantage and the mobility of Edward's 2,000 heavy cavalry were negated by Robert's choice of a narrow, boggy ford as the battle site near Bannockburn village. When the two armies clashed on 23 and 24 June, Edward held back his archers until too late, and the terrain and Scottish pikemen arranged in bristling and mobile hedgehog formations (schiltroms) did the rest. Around 200 English knights were killed in a disastrous defeat. The English king narrowly escaped with his own life. Robert had shown both his skill at leadership and his bravery in battle, meeting the challenge of a one-on-one fight with Henry de Bohun - Robert split his opponent's head with a mighty blow of his battle-axe. After the battle, Stirling Castle surrendered and immense booty was taken from the abandoned English camp.

Scotland had effectively reasserted its independence. Robert negotiated the release of Queen Elizabeth and Princess Marjorie. He also confiscated the lands of those Scottish lords who had supported Edward, giving him ample resources to reward his followers and ensure their continued loyalty. Long-term consequences of this policy were the creation of almost-too-powerful families in certain regions, the creation of enemies amongst the descendants of the disinherited, and the impoverishment of the Crown itself, a development which necessitated taxes merely to pay for the living expenses of the monarch. For the moment, though, Robert was riding high. Berwick was taken in 1318 CE, and the Scottish king continued to raid northern England, almost capturing York in 1319 CE.

Foreign Policy & Recognition

Robert was secure enough in his kingdom after 1314 CE to even consider foreign conquest. In a campaign covering three winters, the Scottish king grabbed Ulster and installed his brother Edward (b. c. 1276 CE) as the King of Ireland in 1316 CE. The Scottish army had been assisted by the locals who were only too willing to rid themselves of the English barons there. However, Edward Bruce proved just as unpopular, and he was killed in battle in 1318 CE. In the end, the Scottish gave up Carrickfergus Castle and withdrew from Ireland.

On 6 April 1320 CE a letter was sent to the Pope requesting a withdrawal of Robert's excommunication and the placing of Scotland under an interdict, both applied because Robert had refused to sign a truce with England back in 1317 CE. The contents of the letter are often called the Declaration of Arbroath, which boldly stated that Scotland was a free and independent kingdom and the English Crown had no rights whatsoever there. This impressive document, which is festooned with the seals of eight earls and 38 barons, still survives today.

Robert, meanwhile, still had a handful of Scottish barons working against him, and a failed assassination plot was ruthlessly avenged in late 1320 CE. In 1322 CE a lacklustre English invasion was repelled. Then, in 1323 CE, a 13-year truce was agreed between England and Scotland. The 1326 CE Treaty of Corbeil formally established an alliance of mutual assistance between Scotland and France (including a clause whereby a French attack on England obliged Scotland to also attack their southern neighbour). Scotland's independence and Robert's right to the throne were recognised by the English Crown in the 1328 CE Treaty of Edinburgh/Northampton. The treaty was sealed with Robert handing over £20,000 and the betrothal of Robert's son David to Joan (b. 1321 CE), the sister of the new king, Edward III of England. The cherry on the cake was the Pope's decision in 1329 CE to allow Scottish monarchs to officially receive a crown and holy anointment during their coronations. The kingdom of Scotland was, for the first time, now on an equal footing with other European monarchies.

Death & Successors

Robert the Bruce died on 7 June 1329 CE at his manor house at Cardross in Dumbartonshire. The king had been ill for two years, the medieval chroniclers describing his ailment as leprosy. Robert was buried at Dunfermline Abbey. However, he had long wished to go on a Crusade to the Holy Land and, never having managed it, he requested that Sir James Douglas take his heart there. Douglas was killed in a battle in Spain, but legend has it Robert's embalmed heart was taken back to Scotland and buried at Melrose Abbey.

Robert was succeeded by his son who became David II of Scotland. The new king was only five years old and so an opportunity was presented for rivals to the Bruce family to try and take power. Edward Balliol (c. 1283-1367 CE), the son of King John Balliol, had the support of Edward III, and David was deposed in 1332 CE. Balliol was made king, but there was another round of musical thrones, and by the end of 1336 CE, David II was back; he would rule Scotland until 1371 CE.

Meanwhile, Robert the Bruce's reputation grew ever grander as he became a favourite of medieval chroniclers and the subject of a celebrated poem The Bruce, commissioned by the king's grandson Robert II of Scotland (r. 1371-1390 CE). A century later, James III of Scotland (r. 1460-1488 CE) was carrying Robert the Bruce's sword in battle. And so it continued over the centuries as Robert became the paradigm of good kingship and a national hero. In more recent times, the king has again piqued public interest with the reconstruction of Robert's face from his skull found at Dunfermline Abbey and the ongoing issue of Scottish parliamentary independence from the United Kingdom.