Roger I, also known as Roger Bosso (c. 1031-1101) was a Norman knight and adventurer best known for conquering The Emirate of Sicily during the 11th century. His lifelong efforts helped lay the foundations of a wealthy new Mediterranean state based in Palermo, known as the Kingdom of Sicily founded in 1130.

Family & Arrival in Italy

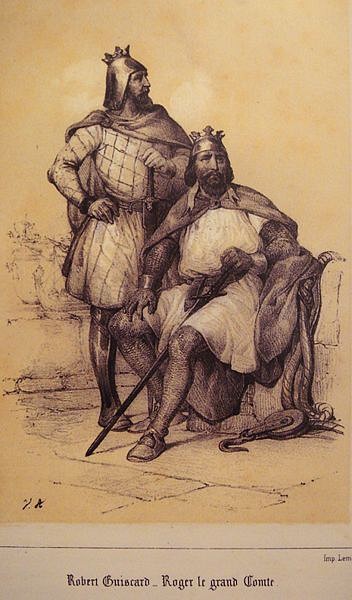

Roger was the youngest of twelve sons from a minor Norman lord, Tancred de Hauteville (c. 980-1041). Roger's numerous brothers and half-brothers included William Iron Arm, Count of Apulia (c. 1042-1046), Drogo, Count of Apulia (c. 1046-1051), Humphrey, Count of Apulia (c. 1051-1057), Geoffrey, Count of the Capitinate (c. 1054-1071), Serlo, Robert Guiscard, Count of Apulia (1057-1059), then Duke of Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily (1059-1085), Mauger, Count of the Capitinate (c. 1053-1054), William, Count of the Principate (c. 1055-1080), Aubrey, Tancred, and Humbert.

The first of Roger's siblings began arriving in Italy as mercenaries around 1035, at the court of Rainulf Drengot (r. 1030-1045), the Norman count of Aversa. Within a few years, the Hauteville brothers would distinguish themselves in battle and demonstrate their capabilities as leaders, ultimately gaining their own noble titles. In 1042, William became the count of Apulia based at Melfi, a title which was then passed on to his younger brothers in turn. Therefore, it was to Melfi that Roger ventured in 1057, where his brother Robert Guiscard had recently assumed the countship. Thus began a relatively fruitful and prosperous relationship between the two siblings.

Roger immediately proved himself a capable leader when helping Robert quell a local uprising in Calabria during 1058. Robert was always busy suppressing rebellions in Apulia, leaving Calabria somewhat thinly garrisoned. The brothers agreed that if Roger would help settle the Calabrian uprising, he would be permitted to claim half the affected lands between the towns of Squillace and Reggio plus all future lands yet to be conquered. Quickly subduing the rebellion, Roger then settled in the castle town of Scalea where he began preparations for future conquests. After taking the Calabrian port city of Reggio in 1060, the Hauteville brothers began plans for an invasion of Sicily, which sits just a few miles across the Strait of Messina.

Battle at Enna

By the middle of the 11th century, Sicily was ruled by roughly four independent emirates, two of which were at odds with one another. The emir, Ibn-al-Timnah (d. 1062) controlled the southeastern portion of the island based around Syracuse and Catania, while another emir, Ibn al-Hawas (d. 1067) maintained control over central Sicily from his hilltop fortress at Enna aka Castrogiovanni. On the losing side of this conflict was Ibn-al-Timnah, who was forced to find creative ways of staying in power. Hearing reports of powerful Norman mercenaries settling in Calabria, Ibn-al-Timnah sought out Roger in early 1061, promising control of Sicily in exchange for help against his rival.

Leading a small reconnaissance force across the Strait, Roger managed to surprise the Islamic garrison of Messina, and quickly occupy the city. With Messina's port in Norman hands, Robert and Roger had a fortified bridgehead where they could bring reinforcements and supplies from their bases in Italy. Furthermore, they had the backing of Ibn-al-Timnah, whose control of eastern Sicily provided the Normans with crucial support for upcoming expeditions to the interior. Initial raids into Sicilian territory were successful during the 1061 campaigning season, culminating with an impressive victory against Ibn al-Hawas outside his fortress at Enna.

Enna sits high up on a mountaintop and would be nearly impossible to storm outright. Therefore, the Normans attempted to lure Ibn al-Hawas' troops out of the citadel to fight on the plains below. The number of troops involved in medieval battles is often exaggerated, though the contemporary chronicler Geoffrey Malaterra records 15,000 of Ibn al-Hawas' troops versus just 700 Normans. This first proper clash between Norman and Islamic armies on Sicily ended in a decisive Norman victory. Though Ibn al-Hawas remained safely inside Enna, the value of this otherwise inconclusive engagement came from the aura of invincibility surrounding the much smaller Norman army, utterly defeating a larger native force.

The victory outside Enna could not be followed up as winter was approaching, so garrison troops were left in occupied towns for the time being. The Hauteville brothers left for Italy at the end of 1061, though Roger planned more Sicilian campaigns the next year despite a persistent shortage of manpower and resources.

The Troina Rebellion

Roger was married in 1061-62, bringing his new bride Judith along with a few troops to the Sicilian city of Troina (west of Mount Etna) in August 1062. After Roger left on campaign the mainly Greek citizens of Troina rebelled, aided by many disaffected Muslim supporters. Quickly returning, Roger was forced back to the main citadel where he would remain besieged by his own subjects for four long months.

By early 1063, Roger's situation was getting desperate with supplies running dangerously low. Noticing that some of his besiegers were drinking too much, Roger and his troops surprised a few inebriated sentries one night, quickly subduing them and retaking the city. Roger immediately hanged the ringleaders and reestablished control in Troina, though the ordeal had been a stark test of survival forcing him not to take the obedience of his new subjects for granted. The experience did, however, demonstrate his resolve, as he was back in the field campaigning later that same year.

The Battle of Cerami

While Roger was besieged in Troina, the Zirid Sultan of Ifriquia (Tunisia), sent two of his sons with large Berber armies to reinforce his Sicilian allies against Norman encroachment. By the summer of 1063, a reinforced Ibn al-Hawas had organized a large army against Roger, whom he met a few miles west of Troina near the town and river named Cerami. Reports estimate Roger's forces at no more than 130 mounted knights, and a few hundred infantry, versus many thousands of Sicilian troops under the emir.

Norman discipline seems to have carried the day against near-hopeless odds. Prior to the battle, Roger sent his nephew, Serlo II (c. 1035-1072) with just 30 knights to safeguard the town, while Roger approached with the vanguard of only 100 knights. From Cerami, Roger marched on to confront the enemy, splitting his forces into two divisions under Serlo and himself. The emir's forces charged Roger's position, ignoring Serlo's men entirely. Serlo then quickly galloped back to support his uncle. After hours of fighting, the less disciplined Berber army began a withdrawal, which turned into a rout ruthlessly exploited by Roger. A few passages by Malaterra describe the encounter:

…their first line, who wanted to seize a hill overlooking our men, avoided Serlo and our advance guard and instead charged our rear division which the count commanded…Both sides now fought bravely, and our men, whose numbers were few, were so hampered by the huge enemy force with whom they were intermingled that scarcely any of them could break out of the melee… Exhausted by the long battle, they were unable to withstand our men's attack any longer and strove to flee rather than fight. Our men pursued them boldly and slew them as they retreated, and, now victorious, they killed some fifteen thousand of the enemy. (48-50)

Victory at Cerami gave Roger virtually uncontested control of the lands between Troina and Messina while demonstrating the Normans' ability to repeatedly destroy forces many times greater than their own. In celebration, Roger sent a gift of camels to Pope Alexander II (r. 1061-1073) in Rome, who was overjoyed at the news. Alexander sent back a papal banner for Roger to carry into battle and provided absolution to Roger and his troops for their victory. This was an important affirmation of support between Roger and the pope, who provided the legitimacy needed for the Normans to continue their invasion and conquest of Islamic Sicily.

The Battle of Misilmeri

After Cerami, the Zirid-Sicilian coalition began to break down, resulting in Zirid reinforcements from Agrigento attacking and killing Ibn-al-Hawas, c. 1067. This gave control of central Sicily to the Zirid prince Ayub, who pursued a pitched battle against Roger outside of Palermo in 1068. Ultimately, Roger and a small raiding party of knights triumphed against the largest Muslim army seen since 1063. Islamic resistance in the field was virtually broken after the Battle of Misilmeri, when Ayub fled back to North Africa leaving the remaining Islamic strongholds on Sicily to fend for themselves.

Norman dominance against their Sicilian counterparts may have been owed in part to their mastery of the massed cavalry charge. To anyone unused to seeing such coordinated maneuvers from horseback, a cavalry charge was intimidating to behold and devastating against the uninitiated. Certainly, Norman confidence in their own abilities played some part as well, as did their battlefield experience, which despite their smaller numbers continued to be effective merits. Regardless, Roger's victories against impossible odds continued to build his mystique and reputation as a gifted general.

Victory at Bari

Roger's various holdings in Calabria and Sicily gave him access to maritime resources, which he used for the development of a burgeoning navy. Therefore, when Robert called on him for help conquering Bari, the last Byzantine stronghold in Apulia, Roger's appearance and veteran troops helped break the stalemate of a three-year siege. It seems that Roger arrived about the same time as a Byzantine relief fleet that was attempting to break through a blockade with needed supplies for the city. Roger's ships managed to capture and scatter this relief fleet, which so discouraged the citizens of Bari that they ultimately surrendered to Robert's forces. Malaterra records the event in the following passage:

Count Roger of Sicily had however arrived with a large number of galleys [plurimo remige] to assist the duke his brother, at the latter's request…The count saw that he was close to the ship of Joscelin, the enemy leader, which was distinguished from the rest by having two lanterns, and ordered his men to attack it. A fierce battle was joined…The count…fought and defeated Joscelin, the latter was taken a prisoner on board his ship, and he returned gloriously and triumphantly to his brother. (59-60)

With Bari subdued, Robert could finally lend the resources needed to help Roger take Palermo, the administrative and symbolic capital of Islamic Sicily.

Palermo & Catania, 1071-1072

After conquering Bari, Roger immediately set out for Sicily, and upon arriving in Messina, he laid plans to quickly capture Catania, a strategic port city to the south. The plan was for Roger's brother Robert to sail down the east coast of Sicily and enter Catania's harbor, asking to resupply his fleet, which he would claim was en route to Malta. Catania had been the domain of Ibn-al-Timnah, and was, therefore, used to seeing Norman shipping. Once Robert's fleet had entered the harbor, it would attack and occupy the city. The plan worked, and the brothers quickly captured another fortified stronghold and valuable port prior to engaging Palermo without months of siege and bloodshed.

From Catania, Roger traveled overland to Troina and then Palermo, where he cut off the landward approaches to the city in preparation for a long siege. Robert arrived soon after with his fleet and began patrolling the coast to discourage efforts at resupplying the city by sea. Within a few months, Palermo's inhabitants began to starve, making the defenders a bit careless. Eventually, a section of the outer wall was left unguarded, which Robert and Roger exploited with siege ladders. The city fell soon after, in early January of 1072.

After taking Palermo, Robert formally invested Roger as the Count of Sicily under his authority as the Duke of Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily. This important investiture provided Roger with an official title, and authority to govern the island in Robert's place.

Roger's Rule

Sicily at this time was inhabited by a large Arabic-speaking Muslim population, with pockets of culturally Greek Orthodox Byzantine adherents. Prior to the Islamic conquest, Sicily was a Byzantine province, and prior to that had formed part of the Roman region nicknamed Magna Graecia ("Greater Greece") due to the cultural and historic ties binding it to the Greek Peninsula. Furthermore, the migration of Lombard Catholics from Southern Italy was encouraged, adding a third cultural and religious group. Roger and his Norman compatriots came as a ruling elite, not as settlers, which meant that he had to govern with some finesse to keep these various groups happy. His solution to handling such diversity was to centralize authority, without disrupting the existing political structure too drastically. He did this partly through his land distribution policies and partly through his benign rule.

Roger avoided the creation of the many small fiefdoms and lordships that plagued the Italian mainland with near-constant rebellion. This ensured that no one lord grew too powerful, negating the ability of his vassals to rebel effectively. The only large donations of land were granted to the Catholic Church, as Roger fully understood the importance of the papacy to his own legitimacy and rule. By 1073, an archbishopric had already been established in Palermo, delighting the papacy by spreading Catholicism to a region of historically Greek Orthodox, and Islamic faith.

Furthermore, Islamic law and religion could still be practiced, while Arabic was added as an official language on equal footing with Latin, Greek, and Norman French. Roger improved the efficiency of tax collection while keeping taxes relatively high for everyone, and adding a period of mandatory conscription for all as well. These policies allowed Roger to centralize authority under him without causing undue animosity from any one group.

Roger also made sound economic decisions. For instance, in 1075, he formed a treaty with his erstwhile enemy the Zirid governor in Tunisia, agreeing to supply Sicilian wheat to North Africa. This treaty tamed the remaining Zirid opposition on the island while creating a lucrative trade deal for Roger. This also protected his southern borders from further Zirid invasions, as they became dependent on Sicilian grain.

The Years After Palermo

Although the fall of Palermo did not in itself constitute the full conquest of Sicily, the remaining Islamic strongholds would eventually fall without further support, which Roger was vigilant in preventing. Robert Guiscard never returned to Sicily after 1072, permitting his brother to claim the remaining territories once they were conquered. Roger's lenient policies made surrender a more palatable option than resistance, ensuring that many towns submitted willingly to his rule in the years after Palermo was taken.

By the 1080s, one of the few remaining holdouts resisting the Norman conquest was a leader in Syracuse, Ibn-al-Ward (d. 1085). He was attacking Norman lands when Roger was called away to settle affairs in Italy and became a dangerous nuisance.

Therefore, in 1085, Roger spent roughly six months pulling together his navy and a substantial army to lay siege to Syracuse. As long as the harbor remained open Syracuse might be resupplied, and after a reconnaissance of Ibn-al-Ward's forces, a maritime attack on the harbor was decided. During the ensuing battle, the longer range of Norman crossbows seems to have made a decisive difference. Although, what decided the day was a miscalculation by Ibn-al-Ward, who tried jumping from one ship to another, accidentally falling into the water and drowning from the weight of his armor. The loss of their commander caused the remaining Islamic forces to scatter or surrender. Though the town held out a bit longer, Roger's army was practiced in siege warfare, and without outside help, the city's fall was inevitable.

Although the final Islamic stronghold, Noto, would not fall for nearly five more years, the conquest of Syracuse essentially marked the end of formal resistance in Sicily, and Roger's subjugation of the island was virtually complete.

Legacy

Through Roger's wise administration and political aptitude, Sicily became something of an enlightened and wealthy trading entrepôt well into the 12th century. His efforts led to the creation of a remarkably stable, and prosperous island state, while his sage and farsighted policies brought together a multitude of faiths, languages, and people. Ultimately, what followed was a rich exchange of culture and ideas rarely seen elsewhere in the Middle Ages at this time. Furthermore, he had become one of the most respected and powerful nobles in Europe, with three European kings seeking him out as a father-in-law. Roger had come a long way from the youngest son of a minor Norman knight to an influential, wealthy, and respected lord of his own county.

Roger's achievements are no less significant for the time period through which he lived. 1095 for instance, marks the official beginning of the Crusades, a time of uncertainty, fear, and religious intolerance, from which Roger was largely able to steer clear. After a lifetime of conquest, Roger recognized the more lucrative advantages of peaceful coexistence with his neighbors to the south. In the decades after Roger's death, Sicily entered a golden age, where the mixture of cultures, religions, and, ethnic diversity created an affluent county from which sprang a kingdom in 1130, upon which his son Roger II would reign as its first king.