Rollo (l. c.860-c.930 CE, r. 911-927 CE) was a Viking chieftain who became the founder and first ruler of the region of Normandy. He converted to Christianity as part of a deal with the Frankish king Charles the Simple (893-923 CE) in 911 CE (changing his name to Robert) and his story was then embellished upon by later Christian writers who held him up as a role model: a savage Viking chief who became a paragon of Christian virtue and established law in the land. In doing so, however, they largely ignored whatever was known of Rollo's life prior to his involvement with Charles.

He is the great-great-great grandfather of William the Conqueror (first Norman King of England, 1066-1087 CE) and ancestor, or supposed ancestor, of a number of European monarchs who trace their line to his immediate descendants. Since 2013 CE, Rollo has been featured in the TV series Vikings in which he is played by British actor Clive Standen. Contrary to his depiction in the series, there is no evidence to suggest that Rollo was the brother of Ragnar Lothbrok but there are suggestions that Rollo did participate in, or even lead, the siege of Paris in 885-886 CE as depicted in the show.

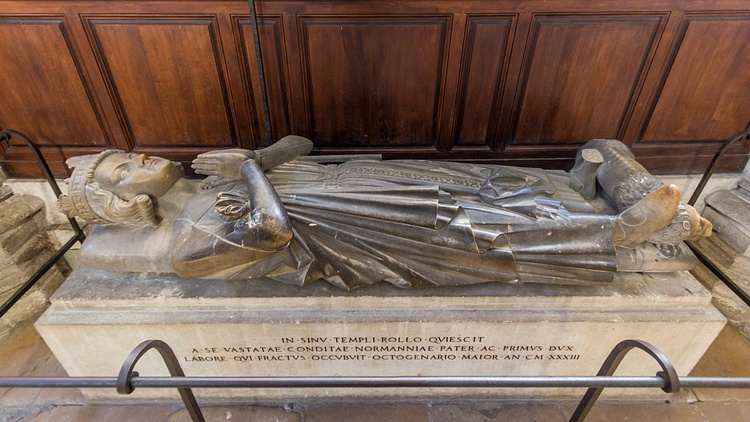

Whoever or whatever he was prior to ruling Normandy, Rollo kept his word to Charles and not only protected the region from Viking raiders but restored order to the land which he had previously helped destroy. He is said to have ruled with a Viking code of law based upon the concept of personal honor and individual responsibility and reformed the weak and ineffectual laws which magistrates had been struggling to enforce prior to his reign. He died sometime around 930 CE, probably of natural causes as no mention of his death appears in any records of the time indicating otherwise.

Early Life & Origins

Many of the details of Rollo of Normandy's life are semi-legendary, as the scholar Robert Ferguson notes:

Also known to his biographers, chroniclers, and poets as Rollo, Rollon, Robert, Rodulf, Ruinus, Rosso, Rotlo and Hrolf, Granger Rolf or Rolf the Walker, founder in about 911 of what became the duchy of Normandy, is another of those, like Ragnar Hairy-Breeches and Ivar the Boneless, whose prominence among their contemporaries conspired over the years with an almost complete lack of biographical information to transform them from ordinary mortals into dense hybrids of men, myth, and legend. (177)

Ferguson's point is well made in that no one knows where Rollo came from, his lineage, or what precisely he did prior to his involvement with Charles the Simple. Even after the foundation of Normandy (from `Northmen' to designate the land of the Vikings) his story is far from certain in that it was ornamented by the Norman historian Dudo of Saint-Quentin (10th century CE) some time around 986 CE in his History of the Normans.

Dudo claims he was an aristocrat from Denmark who raided the Kingdom of West Francia with his fellow Danes prior to his contract with Charles and conversion to Christianity. Dudo also claims he was a friend and comrade of one king Alstem of East Anglia whom scholars have identified as the former Viking leader Guthrum (died c. 890 CE) who was defeated at the Battle of Eddington by Alfred the Great in 878 CE, was forced to convert to Christianity, and rose to the kingship of East Anglia by 880 CE. Rollo's close relationship with Guthrum argues for his Danish origins since it is known that Guthrum was a Dane and, as Ferguson points out, their meeting, as described in Dudo's account, “has the unique ring of one ex-pat fondly greeting another” (178).

It has also been claimed that Rollo was from Norway, again of aristocratic lineage, but this claim appears later in the 11th century CE and was popularized in the 12th century CE in the works of William of Malmesbury (c.1095-c.1143 CE). Rollo's grandson, Robert II Archbishop of Rouen (r. 989-1037 CE) was known as Robert the Dane and it is also clear that the majority of Viking raiders came from Denmark so a Danish origin is not only probable but reasonable. There is no clear consensus on this, however, and recent efforts to finally substantiate Rollo's origins have failed.

In 2016 CE, Norwegian archaeologists were granted permission to open the tomb of Rollo's grandson Richard I (r.942-996 CE) and great-grandson Richard II (r.996-1026 CE) but found that the bodies in the sarcophagus belonged to neither of these men and, in fact, were much older than the time of the Viking raids. Most likely, according to the archaeologists who opened the tomb, the two bodies were placed in the sarcophagus from another grave and those of Richard I and II relocated at an unknown point in the past to protect them from grave robbers. However that may be, it sheds no light on Rollo's origins.

Dudo's account of Rollo's life, and therefore his Danish origins, has been repeatedly challenged by scholars who point out the obvious Christianization of the man and his actions. Even so, Dudo's work is the first to record anything about Rollo (it was commissioned by Richard I) and he had access to Rollo's immediate descendants as well as documents which were then lost.

Every later writer on Rollo, including William of Malmesbury, drew on Dudo's work for their own accounts and so, in spite of later claims of a Norwegian origin, it is most likely Rollo was from Denmark, as Dudo claims, even though many scholars prefer the Norwegian claim of the later Icelandic chronicler/historian Snorri Sturlson (1179-1241 CE) because they find corroboration for his claims in the earlier work of Richer of Rheims (10th century CE). As with many great Viking figures, the legend of Rollo of Normandy eventually overshadowed and then obscured the man's actual life.

Viking Chieftain

It is certain, however, that he was a Viking chieftain who conducted raids in the Kingdom of West Francia. The chronicler Flodoard (c.893-966 CE) describes a Viking raid c. 876 CE which devastated the region around Rouen and this corresponds to what Dudo says of Rollo's activity in the region at the same time. Viking raids in Francia began in 820 CE and continued regularly, with ships making easy incursions up the Seine River, until the peace was concluded with Rollo in c. 911 CE.

The first raid in 820 CE was unsuccessful because the Vikings had no idea of who or what they would encounter once they landed. They were therefore easily defeated by the shore guard and, suffering losses, retreated. When they returned in 841 CE, under the command of Asgeir, they were much better prepared. They sacked and burned Rouen and carried off enormous amounts of loot. This raid was followed by the Norse chieftain Reginherus' 845 CE siege of Paris which only concluded when Charles the Bald (r.843-877 CE) paid the Vikings to leave.

By c.858 CE, the raids on Francia were so lucrative to the Vikings that the famous leaders Bjorn Ironside (allegedly the son of Ragnar Lothbrok and his queen Aslaug) and Hastein (also known as Hasting) attacked the region either just before or following their famous raiding expedition to the Mediterranean. In 876 CE, 100 ships sailed up the Seine to lay waste to the region and this raid was most likely led or co-led by Rollo or, if not, he at least seems to have played a significant role in the event. It also seems fairly certain that he played a significant role in the later siege of Paris in 885-886 CE.

By this time, it was obvious to Charles the Simple that trying to fight off the Viking raiders was futile. The only times West Francia experienced anything close to a positive outcome in these raids was when the king paid the Vikings to leave the cities alone. As Ferguson notes, “the policy of a sometimes well-meaning appeasement had been practiced by Frankish rulers for almost a century prior to the agreement [between Charles and Rollo] and the beneficiaries were Danes” (175).

Their agreement, therefore, was nothing new but simply the continuation of a policy of defense which seemed to work the best. The difference between the contract of 911 CE and the earlier payoffs was the character of Rollo. Unlike the earlier Viking leaders who took their loot and then either returned or encouraged others to raid, Rollo took the deal offered seriously and committed himself to the king and the people he had sworn to protect.

Rollo & Charles the Simple

According to Dudo, the Franks under Charles the Simple finally understood that there was no stopping the Viking raids and they were either going to have to continue to pay whatever price a Viking leader asked or find some new slant on the old policy. The king's counselors asked him why he was not prepared to do more to save his kingdom than he had been doing and he, enraged, basically told them that if they had any better ideas he would be happy to entertain them. Dudo writes that the counselors responded:

If you will trust us, we will give you advice fitting and wholesome for you and for the kingdom, so that the people, who are all too stricken with want, may have repose. Let the land from the River Andelle to the sea be given to the pagan peoples; and in addition, join your daughter to Rollo in marriage. And thereby you will be able to grow mightily in power against the peoples who resist you; for Rollo is born of the proud blood of kings and of chiefs; he is very fair of body, a ready fighter, far-sighted in counsel, seemly in appearance, amenable to us, a faithful friend to those to whom he gives his word, a ferocious enemy to those whom he opposes, a constant and amenable vassal in all things, with a shrewd mind, such as we need. (Dudo's History 2:25)

After considering their counsel, Charles sent the Archbishop of Rouen to Rollo to present the offer. Rollo consulted with his Danish chiefs who pointed out that the land, though presently desolate, had a number of redeeming features and that he should accept the proposal.

Rollo did so and a date was set for his baptism and marriage to Charles' daughter Gisla (also given as Gisela, c. 911 CE). When the day arrived, however, Rollo refused to go through with the baptism, pointing out that the land the king was offering him was in ruin and would take some years to restore to health. The king's counselors advised him to give Rollo whatever he wanted in order to not only protect the kingdom but win souls for Christ who would be impressed by a Viking leader embracing Christianity.

Charles offered Rollo Flanders but Rollo declined because the land was too marshy and so the king then offered him Brittany, which bordered the lands offered in the contract, and Rollo accepted all of it. In order to finalize the deal, and show proper respect to the king, Rollo was then asked to kiss the king's foot but, as Dudo relates:

Rollo was unwilling to kiss the king's foot and the bishops said: “He who accepts a gift such as this ought to go as far as kissing the king's foot.” But Rollo replied: “I will never bow my knees at the knees of any man and no man's foot will I kiss." And so, urged on by the prayers of the Franks, he ordered one of his warriors to kiss the king's foot. And the man immediately grasped the king's foot and raised it to his mouth and planted a kiss on it while he remained standing, and laid the king flat on his back. So there arose a great laugh [from among the Vikings] and a great outcry among the [Franks]. (2:29)

The king and his nobles were not bothered by the upset, however, and Rollo was baptized, married to Gisla, and took possession of his lands in accordance with the Treaty of Saint Clair sur Epte in 911 CE. He instantly engaged in a policy of reformation and renovation as Dudo describes:

He imposed everlasting privileges and laws on the people, authorized and decreed by the will of the chief men, and he compelled them to dwell together in peace. He raised up churches that had been demolished to the ground, he rebuilt temples that had been ruined by the visitations of the heathens, and he made new and extended the walls and defenses of cities. (2:31)

Rollo improved the lands he had been given in every aspect but, just as significantly, honored the treaty he had made with Charles: there are no records of any more Viking raids into Francia after 911 CE.

Rollo of Normandy

Although Rollo is often referenced as the first Duke of Normandy, he never held that title (Richard II, his great-grandson, was the first duke). He is sometimes called Count Rollo by later historians but contemporary documents refer to him simply as “Rollo”. A land grant from 918 CE, for example, mentions “lands which we have granted to the Normans of the Seine, namely to Rollo and his companions, for the defense of the kingdom” (Ferguson, 183). Whatever title he claimed for himself is unknown but early historians like Dudo and Flodoard refer to him as “Chieftain”.

By all accounts, he ruled his kingdom as a Viking chief, reforming passive laws which seemed to merely suggest acceptable behavior and implementing a law code which emphasized personal honor and responsibility. Robbery, assault, and murder were punishable by death but so was fraud as one anecdote makes clear:

Rollo had introduced a decree ordering that farm implements be left out in the field and not taken into the house at the end of the day. To make it appear as though they had done so and been robbed, it seems that a farmer's wife hid her husband's ploughing implements. Rollo reimbursed the man for his loss and ordered the trials by ordeal of the potential suspects. When all survived the ordeals, he had the wife beaten until she confessed. And when the husband admitted that he had known it was her all along, Rollo handed down a finding of guilty on two counts: “The one, that you are the head of the woman and ought to have chastised her. The other, that you were an accessory to the theft and were unwilling to disclose it.” He had them both hung and finished off by a cruel death, an action which Dudo credibly claims so terrified the local inhabitants that the territory became and remained free of petty criminality for a century afterwards. (Ferguson, 186-187)

In another instance, he punished some men who were guilty of dishonoring his reputation and that of his wife by having them executed in the public square of his capital at Rouen. This discouraged others from bearing false witness against their neighbors through gossip and slander.

These measures seem to have appeared harsh to some of the bishops of the region who appealed to the Pope for advice. They were told to view Rollo's conversion, and conversion of the pagans generally, “not as an event but a process which would inevitably take time to complete” (Ferguson, 188). Whatever problems the bishops had with Rollo's reign, they could not argue with his success in maintaining law and order or the prosperity he brought to the land.

Depiction in Vikings and Legacy

In the TV series Vikings, Rollo is the brother of Ragnar Lothbrok who, after the siege of Paris, is left in West Francia to hold a spot on the Seine in order to enable future raids. Having been told by the village seer back home that he would one day rule a kingdom, Rollo is easily persuaded by the Franks to betray his brother's trust and accept their offer of land and marriage to the princess Gisla. As noted, nothing is known of the historical Rollo's youth, upbringing, relatives, or even place of origin and there is no evidence he was related to Ragnar Lothbrok. The historical Gisela of France was a very young girl at the time of her betrothal to Rollo and so her character in the series is fictionalized.

The only events depicted in the TV series which correlate to the historical Rollo are those having to do with the foundation of Normandy and defense of the region; including, apparently, his mastery of the language. Rollo is also said to have been quite tall and broad-shouldered (as he is depicted in the show) and was given the epithet “the walker” because he preferred walking to riding a horse (or, alternatively, was too heavy for a horse to carry).

Rollo retired in c. 927 CE and was succeeded by his son William Longsword (r. 927-942 CE), dying shortly afterwards in c. 930 CE. William Longsword's illegitimate son, Richard I (also known as Richard the Fearless) came to the throne at around the age of ten, following his father's death. Richard I honored the policies of his father and grandfather and this policy would be continued by Richard II.

The reigns of his successors, Richard III (1026-1027 CE) and Robert I (1027-1035 CE) were marked by instability and civil war which ended with the reign of William I (William the Conqueror), who was Duke of Normandy 1035-1087 CE as well as King of England from 1066-1087 CE. William's conquest of England radically changed not only British society but European culture overall and his polices echo those implemented earlier by Rollo of Normandy.