Britain was a significant addition to the ever-expanding Roman Empire. For decades, Rome had been conquering the Mediterranean Sea – defeating Carthage in the Punic Wars, overwhelming Macedon and Greece, and finally marching into Syria and Egypt. At long last, they gazed northward across the Alps towards Gaul and ultimately set their sights across the channel (they believed it to be an ocean) into Britannia. After Claudius' invasion in 43 CE, part of the island became a Roman province in name, however, conquest was a long process. Constantly rebellious and twice reorganized, it was finally abandoned by the Romans in 410 CE.

Britain before Rome

At the time of the Roman arrival, Britain (originally known as Albion) was mostly comprised of small Iron Age communities, primarily agrarian, tribal, with enclosed settlements. Southern Britain shared their culture with northern Gaul (modern-day France and Belgium); many southern Britons were Belgae in origin and shared a common language with them. In fact, after 120 BCE trading between Transalpine Gaul intensified with the Britons receiving such domestic imports as wine; there was also some evidence of Gallo-Belgae coinage.

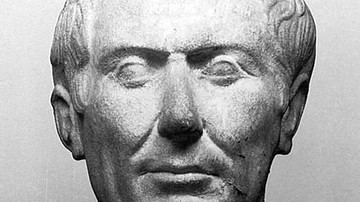

Caesar's Campaign

Although Julius Caesar's presence did not result in conquest, it was this intense trade – some claim it was partly ego – that brought the Roman commander across the Channel in both 55 and 54 BCE. Previously, the Channel, or Mare Britannicum, had always served as a natural border between the European mainland and the islands. During his subjugation of Gaul during the Gallic Wars, Caesar had wanted to interrupt Belgae trade routes; he also assumed the Britons were assisting their kindred Belgae. Later, he would rationalize his invasion of Britain by telling the Roman Senate that he believed the island was rich in silver. Although the Roman Republic was probably aware of the island's existence, Britain, for the most part, was completely unknown to Rome, and to many more superstitious citizens, only existed in fables; traders repeatedly told of the islanders' barbarous practices. To the disgust of many Romans, they even drank milk.

Nevertheless, Caesar's initial contact with the islanders went poorly, and he had to quickly reorganize his army to avoid defeat. During his second 'invasion' when he was accompanied by five legions, he pushed further northward across the Thames River to meet the Briton chieftain Cassivellaunus. Although he was joined for battle by several local chieftains, to avoid crossing the Channel in poor weather, Caesar feigned growing problems in Gaul, arranged a peace treaty with Cassivellaunus, and returned to the European mainland without leaving a garrison. While many Romans were enthusiastic about Caesar's excursion across the Channel, Caesar's worst enemy Cato the Younger was aghast. The Greek historian Strabo, a contemporary of the late Republic, said the only things of value were hunting dogs and slaves. More important to Caesar were the difficulties developing in Gaul, a failed harvest, and possible rebellion. The Romans would not return to Britain for another century.

Claudius' Invasion

With the assassination of Julius Caesar and the civil war that followed, the Republic was no more, and the new Roman Empire's interest in Britannia intensified under both emperors Augustus and Caligula as the Romanization of Gaul progressed. While Augustus' attentions were drawn elsewhere, Caligula and his army stared across the Channel towards the British Isles – the emperor only ordered his men to throw their javelins at the sea – there would be no invasion. The actual annexation fell to the most unlikely of emperors, Claudius (r. 41-54 CE).

In 43 CE, Emperor Claudius with an army of four legions and auxiliaries under the command of Aulus Plautius crossed the English Channel, landing at Richborough. They began the conquest of the island. Some believe the emperor's only goal was personal glory; years of humiliation under Caligula left him longing for recognition. Although he had only been there 16 days, Claudius would take credit, of course, for the conquest with a glorious triumphant return to Rome in 44 CE.

The Roman army had landed on the British shore and marched northward towards the Thames River; it was there that Claudius joined them. Rome's army quickly overran the territory of the Catuvellauni with a victory at Camulodunum (modern-day Colchester). Afterwards, the army quickly moved to the north and west, and by 60 CE much of Wales and the areas to the south of Trent were occupied. Client kingdoms were soon established including the Iceni at Norfolk and the Brigantes to the north. While one legion was sent northward, the future emperor Vespasian led another legion southwest where he would capture 20 tribal strongholds. Cities such as London (Londinium) – because of its proximity to the Channel – and St. Albans (Verulamium) were established.

Revolts & Consolidation

There was, however, considerable resistance; the Britons were not about to quit without a fight. Caratacus, a member of the Catuvellauni, rallied considerable support in Wales only to be captured in 51 CE. After his defeat, he escaped and made his way to a region controlled by Brigantes whose queen quickly turned him over to the Romans. He and his family were taken to Rome in chains. In Rome, a triumph was held to glorify Claudius, but the captured chieftain was given the opportunity to speak to the Roman people:

Had my lineage and rank been accompanied by only moderate success, I should have come to this city as friend rather than prisoner, and you would not have disdained to ally yourself peacefully with one so nobly born … If I had surrendered without a blow before being brought before you, neither my downfall nor your triumph would have become famous. If you execute me, they will be forgotten. Spare me, and I shall be an everlasting token of your mercy.

(Tacitus, Annals, 267)

His life, together with that of his wife, daughter, and brothers, was spared by Claudius.

While Caratacus' revolt was a failure, Rome had yet to tangle with the mighty Boudicca. She was the wife of Prasutagus, a Roman ally and client king of the Iceni, a tribe in eastern Britain. His death in 60/61 CE left a will that gave one-half of his territory to Rome and one-half to his daughters; however, Rome did not wish to share the kingdom and, instead, decided to plunder it all. The result left Boudicca flogged and her daughters raped. Although she and her army would eventually be defeated, she rose up, gathered an army, and with the neighboring Trinovantes went on the offensive. Towns were sacked and burned, including Londinium, and residents killed – possibly as many as 70,000 (these are Roman numbers and may or may not be completely accurate). In his Annals, Tacitus wrote,

Boudicca drove around all the tribes in a chariot with her daughters in front of her. "We British are used to woman commanders in war." she cried. "I am descended from mighty men! But now I am not fighting for my kingdom and wealth. I am fighting as an ordinary person for my lost freedom, my bruised body, and my outraged daughters." (330)

She prayed that the gods would grant her the vengeance the British deserved. Unfortunately, her prayers went unanswered, and instead of surrendering to the Romans, she committed suicide. Tacitus believed that had it not been for the quick response of Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, Britain would have been lost.

Romanization

The Battle of Watling Street was the last serious threat to Roman authority in the lowlands. Aside from his victory against Boudicca, in his desire to strengthen Roman presence, Paulinus also eliminated the Druid stronghold at Anglesey; the Druid religion had always been considered a threat to the Romans and their imperial cult. Accordingly, the governor's rather vigorous response to the Boudicca's surrender led not only to his recall by Rome - he was replaced by Turpilianus – but a change in Roman policy towards Britain. Gradually, Britons were adopting Roman ways. With a stronger presence in Britain, Rome began to make significant changes. Burnt towns were rebuilt. Soon, London (Londinium), serving as the administrative capital, would have a basilica, a forum, a governor's palace, and a bridge crossing the Thames.

Although progress was relatively slow, Rome considered the conquest of Britain necessary. While Julius Caesar had dismissed the island as having little of value, the truth was far from it. Not only was it important for its tax revenue but it was also useful for its mineral resources – tin, iron, and gold and as predicted hunting dogs and animal furs. Mining developed. In addition, there was its grain, cattle, and, of course, slaves. Roads were built; Watling Street which linked Canterbury to Wroxeter on the Welsh border and Ermine Street which ran between London and York. And, with any burgeoning economy, merchants arrived, resulting in increased trade and commerce. However, despite the presence of a strong military, resistance continued, so expansion remained gradual.

Agricola's Campaign

From 77 to 83 CE the military commander Gnaeus Julius Agricola – ironically the father-in-law of Tacitus – served as governor. It was not Agricola's first time In Britain. He had served there as a young man on Suetonius Paulinus' staff as a military tribune. In his On Britain and Germany, the historian wrote about Agricola's previous stay in Britain stating that he was energetic but never careless. Concerning the state of affairs in Britain at the time, he wrote, "Neither before nor since has Britain ever been in a more uneasy or dangerous state. Veterans were butchered, colonies burned to the ground, armies isolated. We had to fight for life before we could think of victory" (55). The Britons were on the defensive. "We have country, wives and parents to fight for: the Romans have nothing but greed and self-indulgence" (65).

The tribune studied his craft well, and in his return to the island as governor, he was prepared. His first order of business was to restructure the army's loose discipline and reduce abuses, thereby giving men a reason to "love and honor peace." With his new army, he marched northward to Caledonia (Scotland) conquering much of northern England along the way.

In a series of conflicts, Agricola was able to achieve victory, subduing northern Wales and finally meeting the Caledonians at Mons Graupius. The governor even eyed the neighboring island of Ireland, claiming it could be taken with only one legion. Unfortunately, Agricola was forced to withdraw from Scotland when one of his legions was recalled by Roman emperor Domitian (81-96 CE) to confront intruders along the Danube. However, despite his attacks against rebels, Agricola was not a cruel conqueror. Aside from the forts he built to the north, he fostered 'civilizing' or Romanizing the Britons, encouraged urbanization, moving into towns that were equipped with theaters, forums, and baths. And, like other conquered lands, Latin was to be taught.

Hadrian's Wall & the Antonine Wall

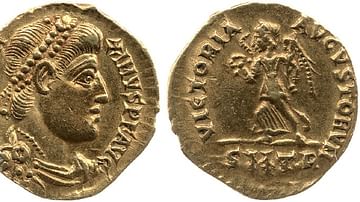

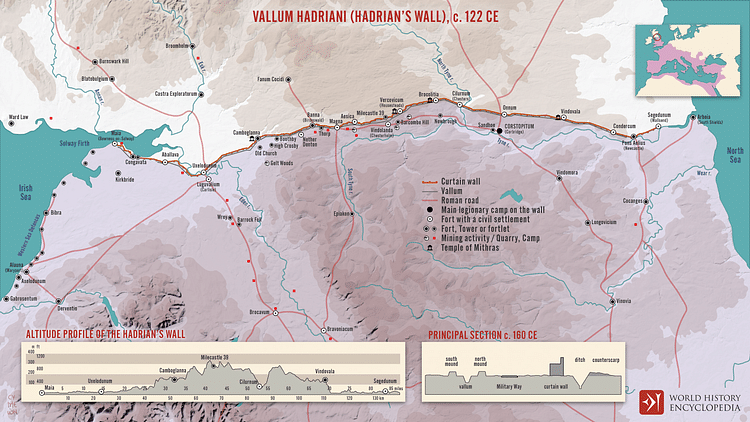

Unfortunately, his success would not go unnoticed by Domitian, who, in a fit of jealousy, recalled Agricola. The territory he had long desired to the north, Scotland, would not be fully conquered for years to come. Eventually, a 73 mile (118 km) long stone and turf wall would be built between the province of Britain and barbarian territories under Emperor Hadrian (117–138 CE). The emperor had visited both Gaul and Britain in 121 and 122 CE and believed that in order to maintain peace the frontier had to be secured. He realized that external expansion meant an increased reliance on strengthening frontier defenses. Although taking years to build and manned with 15,000 soldiers, it seems that it was not to keep the barbarians out but designed solely for surveillance and patrols.

By 130 CE military garrisons had been established throughout Britain. It was at this time that Rome realized the need to further strengthen their army on the European continent and began to recruit from the 'barbaric' provinces of the empire, namely the Balkans and Britain.

In 139 CE another wall, the 37-mile (60 km) long Antonine Wall (named for the Emperor Antonius Pius), was built c. 100 km to the north between the Firth of Forth and the River Clyde; however, it was too difficult to defend, and therefore it was abandoned in 163 CE.

3rd-4th-Century Developments

Further changes soon came to the island. In order to rule more efficiently, the island was divided in half, Britannia Superior governed from London, and Britannia Inferior governed from York (Eboracum). Emperor Diocletian would later divide the province into four separate regions. Because of Diocletian's tetrarchy, Britain was then placed under the watchful eye of the emperor in the west.

Trouble continued to haunt Britain. During the 3rd century CE, the island had been under constant attack by the Picts of Scotland, the Scots from Ireland, and the Saxons from Germany. After a rebellion led by Carausius and then Allectus enabled Britain temporarily to become a separate kingdom, the Roman emperor of the west Constantius (293 – 306 CE) regained control in 296 CE. The emperor had served as a military tribune combatting Celtic tribes earlier in his career. In celebration of his victory, he received a much-deserved title from the people of London 'The Restorer of the Eternal Light.'

Abandonment & Aftermath

However, along with the arrival of Christianity, by the end of the 4th century CE, Rome was having trouble maintaining control of Britain. After Alaric's sack of Rome in 410 CE, the western half of the empire began to undergo significant changes; Spain, Britain, and the better part of Gaul would soon be lost. The eastern half of the empire, based in Constantinople, became the economic and cultural center. The loss of the rich grain-producing provinces doomed Rome. According to historian Peter Heather in his The Fall of the Roman Empire, Britain, unlike other provinces, was more prone to a revolt or break with Rome because many civilians, as well as military personnel, felt left out; attention (primarily defense) was being given elsewhere. Emperor Valentinian I (364-375 CE), who had defeated Saxon insurgents in 367 CE, gradually began to withdraw troops. In 410 CE Honorius, one of the last emperors of the west, pulled out completely; the emperor even wrote letters to individual British cities informing them that they were to 'fend' for themselves. In the final days, Roman magistrates were expelled and local governments were established.

Britain was no longer a province of Rome; however, the years that followed could not erase all of the empire's impact on the people and culture of the island. There was occasional contact with Rome. Missionaries helped Christians battle the heretics, and in the 5th century CE, as attacks from Saxons increased and marauders from Ireland and Scotland raided the English coast, an appeal went out to the Roman commanding general Aetius for help. He never replied. As Europe fell under the veil of the 'Dark Ages,' Britain would break into smaller kingdoms. The Vikings would cross the sea in the late 8th century and cause havoc for decades. Finally, one man would ward off the Viking attempt at conquest and claim to be king of England, Alfred the Great. Britain would recover.