Roman Gaul is an umbrella term for several Roman provinces in western Europe:

Cisalpine Gaul or Gallia Cisalpina, comprised a territory situated in the northernmost part of the Italian peninsula ranging from the Apennines in the west northward to the Alps, specifically the plains of the Po River. It was an area that most Romans did not consider to be part of Italy; to them, Italy only extended to the foothills of the Apennines. The territory was conquered following the capture of Mediolanum (Milan) in 222 BCE, however, it was not until the Social War that the established colonies were organized into a province.

Further north, across the Alps, was Transalpine Gaul or Gallia Transalpina. It spread from the Pyrenees, a mountainous range along the northern border of Roman-controlled Spain, northward to the English Channel - much of modern-day France and Belgium. As the home to a number of Celtic people, many Roman citizens viewed the area with fear and wonder; it was a land of barbarians. The area to the far south from the Mediterranean Sea to Lake Geneva - the closest to Roman Spain (land acquired in the Punic Wars) - had been formed into a province in 121 BCE. In 58 BCE, the future dictator-for-life Julius Caesar would march into Transalpine Gaul, subjugating the whole territory after a decade-long campaign.

A Land of Barbarians

While the Romans were busy displacing a king and building a republic, a number of tribes of Celtic people, who were said to have a warrior aristocracy, migrated across the Alps into the Po Valley. While historical descriptions are scant (Livy wrote briefly of it), archaeological accounts verify the arrival of a number of these tribes: the Insubres in the 6th century BCE, the Cenomani, Boii, Lingones, and lastly the Senones in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. By the end of the 4th century BCE, while making occasional raids across the Apennines into Italy, the Celts completely displaced the Etruscans of Etruria, a small territory located in central Italy, north of Rome. Etruria turned to Rome for help. Unfortunately, Rome's response would bring unrest to the small emerging republic.

From the founding of the Republic through the 3rd century BCE, while the city's government coped with a number of internal political issues, Rome had grown to become a principal power on the Italian peninsula, so it was natural for the Etruscans to appeal to the city for help against the invading Celts. Around 386 BCE (dates vary), the Celts pushed through Etruria and into the heart of the unwalled city of Rome. However, this raid on Rome was not completely without provocation. 15,000 men - Rome's entire army - were sent to face an army twice its number. Sending a small delegation to meet the Celts, Rome hoped for a peaceful solution. Unfortunately, a Celtic delegate was killed by a Roman. In retaliation, the now defenseless Rome was sacked.

According to ancient sources (Roman of course), people quickly fled the city as the last defenders fought heroically, eventually seeking refuge on Capitoline Hill. Senators were butchered where they stood. Forced to pay tribute, the city was torched. There were many who wanted to completely abandon Rome and move to Veii, a city to the northwest, but wiser heads prevailed. Under the leadership of Marcus Furius Camillus, who had assumed the position of dictator, the city was quickly rebuilt. The Celtic raids would continue until the Romans prevailed at the Battle of Telamon in 225 BCE. The destruction, however, had a two-fold effect on the citizens of Rome: the incentive to build the Servian Wall and an intense loathing for the Celts and Gaul, a hatred Julius Caesar would later use as a ploy for his invasion.

The first Roman colonies

From Telamon, the confident Romans, together with their allies, advanced into Cisalpine Gaul in a three-year campaign capturing Mediolanum (Milan) in 222 BCE. In 218 BCE, Roman colonies were established at Placentia and Cremona on the banks of the Po River. Unfortunately, further advancement was halted during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) when Hannibal Barca and his army of 30,000 infantry, 9,000 cavalry, and 37 elephants crossed the Alps, advancing towards Rome. His invasion prompted many of the newly conquered Celts to join him; however, following the defeat of Carthage at Zama in 202 BCE, the Romans would resume their attack against Cisalpine Gaul, ending with the both the massacre of the fiercest of all Gallic tribes, the Boii, in 191 BCE and the rebuilding of Placentia and Cremona. Other colonies were soon built at Bononia, Parma, and Mutina. Gradually, after the Social War in the early 1st century BCE, residents from the southern peninsula began to move into the area. Although much of the Gallic culture would remain, Romanization had begun. Cisalpine Gaul would soon become a Roman province with its southern border extending to the Rubicon.

From the relative safety behind the walls of Rome, its citizens looked across the Alps into Transalpine Gaul, the vast region from the Pyrenees northward to the English Channel. After Julius Caesar returned from his decade-long subjugation in 49 BCE, the entire area would become Roman. His adopted son and heir, Emperor Augustus, would divide the vast territory into four provinces: Narbonensis in the southeast, Lugdunensis lying just north of the Pyrenees, Aquitania in the center and to the north, and Belgica - present-day Belgium. Although mostly Celtic in culture, Transalpine Gaul included several native tribes: Ligurians and Iberians to the south (an area heavily influenced by Greek colonization) and Germans to the northeast. Not all of the territory was alien to Rome. The area to the far south from the Mediterranean Sea to Lake Geneva - the closest to Roman Spain (land acquired in the Punic Wars) - had been formed into a province in 121 BCE with its capital at Narbo. It would become the province of Gallia Narbonensis. This area, especially the city of Massalia, had served as a corridor for trade and travel from Spain to the Italian peninsula and Rome.

Still, much of Gaul was fairly unknown to Rome and simply labeled Gallia Comata or long-haired Gaul. In the opinions of many Romans, all of Gaul was barbaric, but, of course, most Romans saw anyone who was not Roman to be a barbarian. Oddly, when Julius Caesar arrived, he did not find a land of barbarians. While there may have been few roads and no aqueducts, there were walled urban or administrative centers called oppida, built on hills for easy defense. Needless to say, these centers were unlike the cities one would find in other Roman territories; there were no public baths, forums, or gladiatorial contests. The people of Gaul were excellent metalworkers, great horsemen, and skilled mariners. However, everything was soon to change, for Gaul would never experience anything like Julius Caesar again. For ten long years, the future dictator would march across Gaul earning himself both fame and fortune, returning to Rome a conquering hero.

Caesar & The Gallic War

After his one-year term as consul had ended, he was appointed the governor - on Pompey's urging - of Cisalpine Gaul, Illyricum, and Transalpine Gaul. In 58 BCE Julius Caesar and his army crossed the Alps into Transalpine Gaul on a five-year campaign; it would be extended for another five years in 56 BCE. Caesar had alienated many in the Senate during his year as consul, especially his archenemy Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the Younger). The Roman Senate conservatives who had no love for Caesar had hoped he would serve quietly in Rome after his consulship, but he chose otherwise. During his long campaign through Gaul, he would write a series of dispatches to the Senate. Written in the third person, these dispatches would become his Commentaries on the Gallic War. In the opinion of many of his contemporaries and later historians of the period, they were an attempt to rationalize his abuses, demonstrating his talents as a general and his role as a loyal servant of the Republic.

Despite his support from the Roman people and a few in the Senate, there were others who believed he only wanted to justify his brutal tactics. In an appeal to the people, he reminded them of the savagery of the Gallic people and their invasion and sacking of Rome decades earlier. The historian Suetonius wrote in his The Twelve Caesars about a number of discussions held in the Senate while he was in Gaul. Caesar may have been disliked by many in the Senate but the people loved him. Suetonius wrote,

…some speakers went so far as to recommend that Caesar should be handed over to the enemy. But the more successful his campaigns, the more frequent the public thanksgivings voted; and the holidays that went with them were longer than any general before him had ever earned. (19)

Whatever the Senate may have believed, Caesar had a good reason - at least in his mind - to advance into Gaul. The Helvetii, a Gallic tribe from southern Germany, were planning to migrate into eastern Gaul, a plan that would threaten the safety of the region. The Helvetii marched through land occupied by the Aedui who wisely appealed to Caesar for aid. Quick to act, Caesar and his army defeated the Helvetii at the Battle of Bibracte in 58 BCE, forcing them to retreat.

At first, many of the Gallic tribes welcomed Caesar; however, they soon realized that the Romans were not rescuers but there to stay; their warm greeting was soon replaced by a cold shoulder. Tribe after tribe fell to the Romans. As the dispatches reached Rome, people eagerly began to follow Caesar's exploits. The Senate could no longer object, although many still believed his conquest to be nothing more than genocide. Caesar continued across Gaul with little opposition, exploiting the rivalries among the various tribes. He defeated the Germanic king Ariovistus, routed the Germans at Alsace, marched against the Belgae in 57 BCE, and crushed the Veneti of Brittany. In 55 BCE, he looked across the English Channel and chose to invade Britain. Initially, Caesar said he wanted to interrupt Belgae trade routes, but some maintain it was his ego that brought the commander across the Channel in both 55 and 54 BCE. Nevertheless, Caesar's initial contact with the Britons went poorly. In his second invasion, he pushed northward across the Thames River but soon feigned growing problems in Gaul and returned to the European mainland.

Romanization

In 52 BCE, under the leadership of Vercingetorix, the once loyal Arverni challenged Caesar, eventually defeating him at Gergovia. The king's victory was due to a number of old-fashioned maneuvers: the scorched-earth policy, basic guerilla tactics, and a simple knowledge of the terrain. Later in the same year, the two armies would meet again at Alesia with different results. As the king sat behind the well-fortified walls of the city, Caesar and his army waited patiently outside, planning to starve the Gauls out. With his reinforcements defeated by Caesar, Vercingetorix had little choice but to surrender. Many of the defeated Arverni soldiers were sold into slavery. The beaten king would spend the remainder of his life in Rome as a prisoner only to be put to death in 46 BCE.

This final victory spelled the end of the Gallic War in which over 1,000,000 were killed or enslaved. Caesar proudly announced that Gaul had been pacified. With Caesar returning to Rome, Romanization of Transalpine Gaul began, Latin was introduced, and many of the old settlements in Gaul were abandoned with new towns of 'brick and stone' being built, something that made for easy access and not for defense. These new cities were very Roman with bath houses, temples, and amphitheaters. Veterans of the war were granted land which caused agriculture to flourish, much appreciated by a growing Rome. New roads were built allowing for increased commerce. Although there was the occasional rebellion - one in 21 CE led by the Treveri and Aedui, and another in 69-70 CE led by the Batavian Julius Civilis - Gaul would demonstrate little resistance. However, while stability reigned for several decades in Gaul, chaos soon disrupted the peace and quiet.

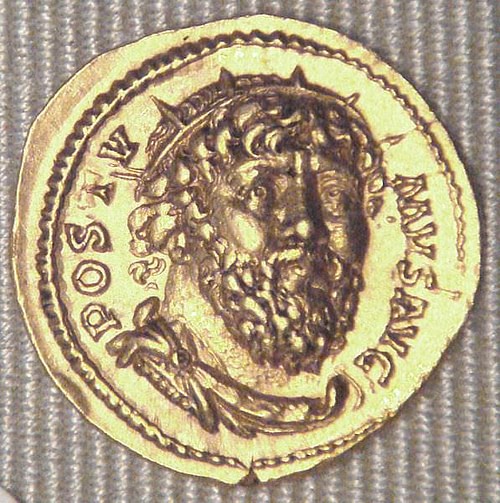

Postumus & the Gallic Empire

The 3rd century CE brought disorder; the Alemanni raided Gaul and Italy while the Franks moved into Spain, destroying Tarraco. The Pax Romana - Roman Peace - was gone. Emperor after emperor rose to power through the military only to fall victim to his own troops. In a fifty-year period from 235 to 285 CE, there were at least twenty emperors with the majority either dying in battle or through assassination. In 260 CE, a military commander and governor of Germania Inferior and Germania Superior (Lower and Upper Germany) Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus (whose family was Gallic in origin) rose up against the Roman emperor Gallienus, seizing power, killing the emperor's son and protector, and establishing himself as the new emperor in Gaul, Britain, and Spain; Spain would later rebel and rejoin Rome.

Although Gallienus marched against Postumus, direct conflict was eventually aborted. While Postumus was opposed by imperial forces and suffered defeat, he and Gallienus would never meet in serious battle. The emperor was forced to withdraw, having received a serious wound. Afterwards, the new emperor of the so-called Gallic Empire would establish his capital and residence at Augusta Treverorum complete with a senate. Surprisingly, he made no attempt to march on Rome. The new empire (260 – 274 CE) would last through four emperors: Laelianus, Marius, Victorinus, and Tetricus. In 269 CE, Roman Emperor Claudius II sent a small expeditionary force against Victorinus but chose not pursue a full confrontation. In 274 CE, Emperor Tetricus and his son marched against Roman Emperor Aurelian at Chalons-sur-Marne and were defeated. Gaul and Britain were reunited with Rome.

Fall of the Roman Empire

However, the next few years proved to be no better for Gaul. Emperor Probus (276 to 282 CE) saw devastation in both Gaul and the Rhineland by the Franks, Vandals, and Burgundians. It would take over two years to restore order. Two decades later the area would fall under the leadership of the future emperor in the East, Constantine. With his death in 337 CE, his eldest son Constantine II received control of Gaul, Britain, and Spain. Upon his death at Aquileia, his brother Constans took sole leadership only to fall to a palace conspiracy and yield the throne to his brother Constantius II in 353 CE. He eventually divided his power with his cousin Julian the Apostate. In 406 CE, Vandals were among many 'barbaric' tribes to cross the Rhine and ravage Gaul. Visigoths were next, and then there was Attila the Hun. By the fall of the western half of the empire in 476 CE, Gaul had already fallen into the hands of the Franks, Burgundians, and Visigoths.

Both Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul proved to be of great value to both the Republic and the Empire, providing agricultural goods and soldiers for the Roman army. Unfortunately, over time, Rome was unable to maintain its borders against invasions from the north and east. By this time, like the rest of the empire, Christianity was flourishing, becoming the recognized religion of the empire. The fragile economy of the western half of the empire was in serious decline - Rome was no longer the city it once had been, even the emperor would not live there. The empire's economic and cultural dominance was in the east at Constantinople. Eventually, Gaul, Spain, and the other provinces in the west fell to a number of invading tribes, the Franks, the Burgundians, the Vandals, and Visigoths. In 476 CE Rome was sacked and the empire, at least in the west, was no more.

Post-Roman Gaul

Roman Gaul became Visigothic Gaul until Clovis came to the throne as king of the Franks in 481 CE. Clovis would eventually drive the Visigoths into Spain, defeat the Burgundians and Alemanni, and thereby consolidate all of Gaul. In November 511 CE, Clovis died leaving a kingdom to his sons, which was a combination of Roman and Germanic culture, language, religion, and law. By the time of his death, he had extended his authority from the north and west, southward to the Pyrenees. He is considered by many to be of both the founder of Merovingians dynasty and France.