The Roman imperial cult was the practice of venerating Roman emperors and their families as having divine attributes, honoring their contributions to the spread of Roman religion and culture. It was instituted by the first Roman emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) in his reforms and transformation of the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire.

Divine Kingship & Hero Cults

Ancient cities had foundation myths, claiming that a god or goddess or the son of a god or goddess provided law codes that dictated proper religious rituals, social behavior, and gender roles. Passed down through the generations, the will of the gods was carried out by the governing authorities. Thus, the concept of divine kingship validated their rule.

Greece also had hero cults. The heroes of Greek mythology were the offspring of a god or goddess or the result of sexual intercourse between humans and the divine. A prime example was Herakles/Hercules. Heroes were rewarded for their great deeds by being among the gods after death, or at least in the higher realms of the Elysian Fields in Hades. The concept was described as apotheosis ("deification"); the hero would reach the levels of the divine and would be worthy of worship and honor. There were dozens of temples and shrines for heroes.

The patron/client system (how things got done) provided the network for relationships for the common good, including relationships between humans and the divine. The word "patron" came from the Latin "defender". The upper classes (aristocrats) offered benefits to the lower-class poor, distributing food during religious festivals. The lower classes reciprocated through their labor, agricultural products, and trades. The tombs of the heroes became the object of pilgrimage, where people petitioned them as patron gods, mediators between the Olympians and the community for special benefits and protection.

Ancient Rome

Rome absorbed major elements of Greek culture. Hercules was also a hero who helped found the city of Rome, but Roman foundation myths were more concerned with honoring the men of the founding families who became the first kings of Rome. Romulus and King Numa were credited with establishing the elements of Roman religion and culture and both were deified after their death.

The closest concept of a hero cult in Rome was the ritual of the Roman triumph. A serving magistrate who waged a successful war against an enemy and personally saved a unit of his legions was acclaimed imperator ("commander") in the field. The Roman Senate then conferred the right of a triumph, a parade in Rome where the individual represented the god Jupiter for a day.

Rome promoted the concept of genius in humans, an element of the divine nature manifest through dignitas, a person's social standing, reputation, and moral worth. Personified in the concept of the paterfamilias, Roman men performed the household religious rituals and served as priests, augurs, and pontiffs in Roman religion. All elected magistrates of the Roman government were empowered with imperium, the religious authority to uphold and carry out the dictates of the gods. They were not worshipped after their death but became role models for subsequent generations.

From Monarchy to Republic

Several of the later kings were Etruscan invaders (an ancient Italic people) but were denounced as tyrants. Rome eliminated kings with the formation of the Roman Republic, c. 508 BCE. The highest rank was the consul, two of them ruling through the Senate. Rome expanded its rule throughout Italy and countries bordering the Mediterranean, and, beginning with some famous generals, hero cults began to take hold. After Scipio Africanus had defeated Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), people made pilgrimages to his grave and then others, leaving mementos and memorializing their virtues and great deeds in stories.

In the 1st century BCE, several Germanic tribes invaded Gaul and northern Italy, the king of Pontus, Mithridates VI (r. 120-63 BCE), conquered the Roman province of Asia, and the allied cities in Italy rebelled over their citizen status in the Social War, 91-87 BCE. Some men were elevated as "first citizens" to lead the republic out of these crises. After the Social War, Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138-78 BCE) led an army into Rome and became dictator. A dictator could confer martial law and was not responsible for subsequent lawsuits during his rule. He reformed the government in favor of the Senate and removed the power of veto in the Plebian Assembly. He proscribed his enemies in a "reign of terror," through mass executions. The period after his death is notable for senatorial and Plebian factions either upholding or trying to undo Sulla's constitution.

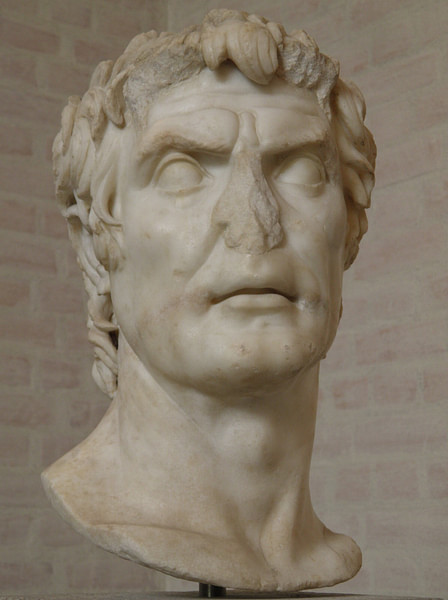

Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE), Sulla's nephew by marriage, created the First Triumvirate with the general Pompey (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus) and Marcus Licinius Crassus. Crassus died fighting against the Parthian Empire at the Battle of Carrhae, 53 BCE. In a subsequent civil war, Caesar defeated Pompey at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE. While in the East, he permitted some cities to erect statues of himself, with the epithet "divine Julius". The family of the Caesars claimed that they were the descendants of the founder of Rome, Aeneas, the son of Venus.

Ceasar created legislation to restore the Roman law. He had been elected as the pontifex maximus, the chief priest of Roman religion, and so his changes were validated in relation to Roman religion. The Senate granted him the title of dictator for life. Many senators saw his rise as going against the mos maiorum, the customs of the ancestors, and a group of them assassinated him over their claim that he aspired to be king of Rome.

Although a patrician (upper-class), Julius Caesar was popular with the common people. He grew up in a tenement in Rome's Subura district, populated with foreigners and the lower classes. During his funeral in the Roman Forum, the common people raided the basilicas for furniture, piled it on the pyre, and burned him there. Although the Senate ordered it cleaned up afterward, people continued to leave flowers and mementos at the site, as well as the site of the assassination of Julius Caesar in Pompey's theater.

Octavianus/Augustus

Caesar left no direct heirs. He had a son, Caesarion, with the queen of Ptolemaic Egypt, Cleopatra VII, but he was not recognized as legitimate in Rome. His one daughter, Julia, married to Pompey, died in childbirth. His will left everything to his 18-year-old great-nephew, Octavianus, through the process of legal adoption. As the heir, Octavianus went to Rome to put on funeral games for Julius. During the games, a comet appeared over the city for three nights. The common people claimed that this was a sign that Julius was “with the gods.”

Octavianus and Mark Antony, Julius Caesar's cousin, divided the empire into Eastern and Western regions, but ultimately Antony joined Cleopatra and challenged Octavianus. They were defeated at the sea Battle of Actium in Greece in 31 BCE, and both committed suicide. Octavianus murdered Cleopatra's son and added Egypt as a senatorial province.

Octavianus became the "first citizen", princeps. The English "emperor" derives from the Latin imperator. Through adoption, he was now Octavianus Caesar, which became the official title for subsequent emperors. The role of pontifex maximus became an inherited function of emperors. The Senate voted him the title of Augustus ("esteemed one") in 27 BCE. Moving from a republic to an empire, all rule was centralized under his authority. Elections for magistrates continued, but Augustus chose the candidates. As Julius' heir, he later had coins issued with the title, "son of god".

The Imperial Cult of Roma

After the end of the war with Antony, the Eastern client kings of Rome traveled to the city to indicate their loyalty and allegiance. They petitioned Augustus for permission to build temples and offer sacrifices to him. Initially refusing because Romans did not worship their magistrates, his advisors recognized the fiscal and propaganda advantage of these temples, and so he granted permission. They could erect a temple to the goddess Roma, an abstract concept of all the virtues of Roman civilization. Roma could be petitioned for the prosperity of the empire as a whole and not just the emperor. In the provinces, the imperial cult was now a way to 'climb the ladder' in terms of status. In order to replenish the Treasury after the last civil war, priesthoods of the cult were sold to the highest bidders.

Augustus extended the Roman worship of the lares, ancient household deities that oversaw property and the family. He claimed that the lares of his family would protect his new Pax Romana, "the Roman peace". His Altar of Peace, the Ara Pacis Augustae was dedicated in 13 BCE. It highlighted all the members of the imperial family, natural as well as adopted.

Imperial temples were established throughout the empire, from Roman Britain to North Africa. As an addition to the imperial temples, Augustus published his Res Gestae, a list of all of his deeds and titles during his reign. Myths emerged that his mother, Atia, Julius Caesar's niece, had been impregnated by the god Apollo. The vast extent of the Roman Empire contained distinct ethnic groups and their various gods. The imperial cult did not replace these ancient traditions but provided a layer of Romanization that unified the new empire. The precedent was established for the deification of emperors, but only after their death. When Augustus died in 14 CE, he was deified by the Senate.

The Julio-Claudian Dynasty

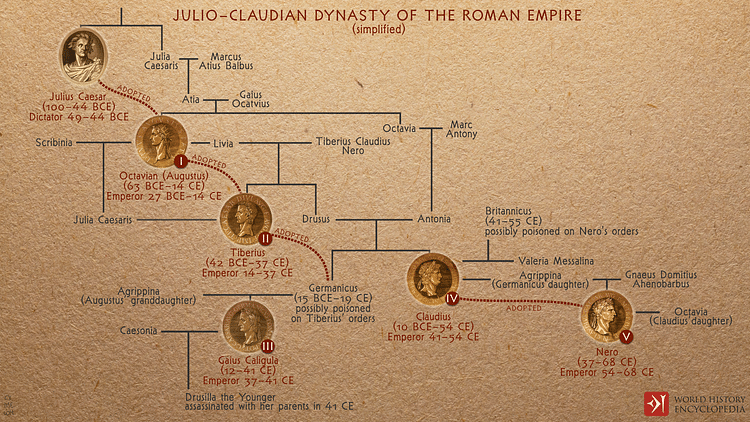

The next few emperors were the descendants of Augustus and Livia Drusilla's lineage from the founding family of the Claudians. Augustus adopted the two sons of Livia by a previous marriage, Tiberius, and Drusus. Drusus died fighting in Germania, leaving Tiberius the heir. The Julio-Claudians had complicated intermarriages of sons and daughters with cousins, nieces, and nephews. Later Roman historians detailed rumors of sexual scandals, poisonings, and executions in the reigns of Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. Only Claudius was deified after his death.

Nero became infamous for the first persecution of Christians, blaming them for a devastating fire in Rome in 64 BCE. The story first appeared in the Annals of the historian Tacitus, written c. 110 CE. It should be noted that we have no contemporary witnesses for the story. If Nero did this, it was an aberration; in this period, there was no official policy concerning Christians.

Flavian Dynasty

Nero's reign ended with his forced suicide in 68 CE. At this point, any continuing reign of the Julio-Claudian family was incredibly unpopular. What followed was the year of the four emperors, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. They were generals who had the support of their legions in Germany, Spain, and Egypt. The winner was Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE), of the Flavian family. He was sent by Nero to put down the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE in Judea. Upon Nero's death, he left the war in Judea to his son Titus, who led the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE, which culminated in the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

The Flavians were tax-gathering public servants. Vespasian proceeded to restore the economic productivity of the empire. In consolidating Roman power in his wars in the East, Julius Caesar utilized Jewish mercenaries in the Roman army. Returning in triumph to Rome, Caesar rewarded Jews with the privilege of continuing to practice their ancestral customs, exempt from the state cults of Rome. Inherent in his legislation was that Jews were not to recruit outside the synagogue nor interfere with the customs of Rome. Vespasian kept the edict intact but issued a Jewish tax. Jews voluntarily sent funds to Jerusalem for the maintenance of the Temple, but it no longer existed. They were to collect the funds but send them to Rome for war reparations for the revolt. Vespasian was succeeded by his elder son, Titus, who only ruled for two years. Both were deified after their deaths.

Vespasian's second son, Domitian (r. 81-96 CE), renewed all the policies that usually got emperors killed. He employed spies to report conspiracies among senators and executed them so that he could confiscate their estates for the treasury. There were rumors that he murdered Titus. Domitian allegedly ordered people to address him as "Lord and god", as a living deity. He mandated that everyone offer sacrifices to him at the imperial temples. However, Paul the Apostle, in his establishment of the first Christian communities, eliminated the traditional sacrifices to the gods, and Christians refused to obey the mandate.

The Crime of Atheism

The modern word "atheism" comes from the Greek atheos ("godless"). It did not deny the existence or belief in the other gods but indicated impiety, sacrilege, and disrespect of the gods. As the gods were responsible for the prosperity of the empire, angering the gods imperiled everyone.

Seeking more revenue, his advisors reminded Domitian of the Jewish Tax. Apparently, it had not been enforced in Rome or the provinces. Domitian sent the Praetorian Guard throughout Rome hunting out the Jews. An earlier decision by the Christian communities was that pagan converts were not required to adopt the identity marker of Jews, such as circumcision (Acts 15). Therefore, as the adherents of early Christianity were not ethnic Jews, they were not liable to the tax, but it also meant that they had no legal exemption, and refusing to honor the mandate of the imperial cult was unpatriotic and the equivalent of treason. Treason, always and everywhere, carried the death penalty. Thus, Christians and others were executed in the arenas. Domitian was stabbed to death by some advisors and Praetorians in 96 CE. He was not deified.

In the history of Christianity, the imperial cult ultimately became the reason for the ordeals and sufferings of Christians. The cult personified everything that was wrong with paganism. Christian refusal resulted in martyrdom, with the reward of achieving heaven in the afterlife. Traditional histories of Christianity list thousands dying in the areas. However, there is little historical evidence for vast numbers. Over the course of 300 years, we have periods of persecution perhaps seven or eight times, and usually only in the provinces. This is because persecution was directly related to a crisis.

Rome's response to the spread of Christianity intensified whenever there was famine, drought, an earthquake, plague, or an invading army. This was when Rome persecuted Christians for angering the gods. When times were normal and prosperous, Rome paid little attention to what Christians were doing or preaching if they did not foment rebellion or interfere with established social conventions.

A second element of illegality was related to collegia. Collegia were trade and social groups that formed clubs under the auspices of a god or goddess. But collegia had to be granted a license to assemble by the Senate. Christians were not granted this permission for 300 years. Pliny the Younger (61-112 CE) served as the governor of Bithynia-Pontus. In his correspondence with Emperor Trajan (r. 98-117 CE), he reported that Christians were meeting in illegal collegia, and attendance at the imperial cult temples was neglected because of their recruiting. Our earliest descriptions of Christian trials come from the writings of Pliny the Younger on Christianity.

Subsequent Roman Emperors & The New Imperial Cult

Between 250 and 300 CE, the empire suffered the Crisis of the Third Century: soaring inflation, plagues, invading armies on the borders, and several coups by generals usurping the throne as barracks emperors. Maintaining the elements of the imperial cult, divergent and oppositional views against each new emperor led to persecution and execution. As with all statistics in the ancient world, numbers are difficult to verify, but with the eventual dominance of Christianity, their stories were omitted in the Western tradition.

Emperor Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) legalized Christian assemblies in 313 CE with the Edict of Milan. Constantine’s conversion to Christianity ended the persecution of Christians. At that time, Christian bishops were in open dispute because some Christians had lapsed in the earlier persecutions by performing the sacrifices. Should they be driven from the church or forgiven? The bishops asked Constantine to intervene in the dispute. With his overriding concern for unity, Constantine ordered lapsers to be forgiven. This essentially made him both head of the empire and head of the church.

Due to riots and debates over the question of the relationship of Jesus Christ to God (the Arian controversy), Constantine called for the First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE. This resulted in the Christian concept of the Trinity, that Christ was the identical essence of God, manifest as a human on earth. It also produced the Nicene Creed, what all Christians should believe and practice.

Christian emperors were now elevated as the new Imperial cult. The emperor stood in for Christ until he returned to usher in the kingdom of God. Any Christian who deviated from the theology of the Christian emperor was deemed a heretic against the concept of orthodoxy ("correct beliefs"). Because he was the head of the state, heresy was the new treason, carrying the same death penalty. The sacredness of Constantine and subsequent Christian emperors was demonstrated through iconography, with haloes surrounding their heads. Further elevation declared Christian emperors as saints in heaven after their death.

When Emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) issued an edict that Christianity was the only legal religion throughout the empire, imperial temples and public basilicas were converted to Christian churches. He also ordered the cessation of the Olympic Games because they were dedicated to pagan gods. They were only reinstated in 1896.