Roman laws covered all facets of daily life. They were concerned with crime and punishment, land and property ownership, commerce, the maritime and agricultural industries, citizenship, sexuality and prostitution, slavery and manumission, politics, liability and damage to property, and preservation of the peace. We can study these laws today thanks to ancient legal texts, literature, papyri, wax tablets and inscriptions.

Roman Law was established through a variety of means, for example, via statutes, magisterial decisions, emperor's edicts, senatorial decrees, assembly votes, plebiscites and the deliberations of expert legal counsel and so became multi-faceted and flexible enough to deal with the changing circumstances of the Roman world, from republican to imperial politics, local to national trade, and state to inter-state politics.

Historical Sources

One of the most important sources on Roman law is the Corpus Iuris Civilis, compiled under the auspices of Justinian I and covering, as its name suggests, civil law. One of its four books, the massive Digest, covers all aspects of public and private law. The Digest was produced in 533 CE under the supervision of Tribonian and is an overview of some 2000 separate legal volumes. These original sources were written by noted jurists or legal experts such as Gaius, Ulpian and Paul and they make the Digest one of the richest texts surviving from antiquity, as within there is a treasure trove of incidental historical information used to illustrate the various points of law, ranging from life expectancy to tax figures.

Other collections of laws include the 3rd century Codex Gregorianus (issued c. 292 CE) and the Codex Hermogenianus (issued 295 CE), both named after prominent jurists in the reign of Diocletian and collectively including over 2,500 texts. There is also the Theodosian Code, a collection of over 2,700 laws compiled in the 430s CE and added to in subsequent years and, finally, the Codex Iustinianus (528-534 CE) which summarised and extended the older codexes.

Then, there are also specific types of legal documents which have survived from antiquity such as negotia documents which disclose business transactions of all kinds from rents and lease agreements to contracts outlining the transfer of property. Inscriptions too, can reveal laws and their implications, as placed on public monuments they publicised new laws or gave thanks for court victories to those who had aided the party involved.

Sources of Law

Roman law was cumulative in nature, i.e. a new law could be added to the legal corpus or supersede a previous law. Statutes (leges), plebiscites, senatorial decrees (decreta), decided cases (res iudicatae), custom, edicts (senatusconsulta) from the Emperor, magistrates or other higher officials such as praetors and aediles could all be sources of Roman law.

In tradition, the first source of Roman law was the Twelve Tables, which survives only as citations in later sources. Following an initiative to collect in one place the civil laws (ius civile) of the early Republic and end the exclusive domination of matters of law by the priestly and patrician class, a code of law governing relationships between citizens was compiled which was separate from sacred law (ius sacrum). This document was actually a collection of sentences concerning the rights of citizens only as all other parties came under the legal jurisdiction of the male head of the family (pater familias), who had considerable freedom in his treatment of those in his care, both free and unfree.

The Twelve Tables became of limited use when legal issues arose which they did not cover, for example, as commercial activity spread it became necessary to provide legal coverage of transactions and business deals between citizens and non-citizens and have laws which considered the behaviour and intent of the parties involved. These relationships became the focus of contracts and provisions such as a stipulatio and, from c. 242 BCE, disputes were presided over by a special magistrate (praetor peregrinus) specifically concerned with legal disputes involving foreigners and relations between Rome and foreign states, i.e. international law (ius gentium).

In the Republic the emphasis was more on the adaptation of existing laws by magistrates (ius honorarium) rather than the creation of whole new legislation. This was done particularly in the annual Praetor's Edict (codified from 131 CE) when the types of permissible cases, defence and exceptions were outlined and an assessment made of the previous year's legal policy, making any needed legal alterations accordingly. In this way it was the application of laws which could be adapted whilst the law itself remained unchanged and so a series of case formulae accumulated to give greater legal coverage for the ever-changing situation of Roman society. For example, an increase in the value of a fine could be made in order to keep pace with inflation but the legal principle of a fine for a particular offence remained unchanged. So too, other officials such as governors and military courts could 'interpret' the law and apply it on a case by case basis according to the particular individual circumstance.

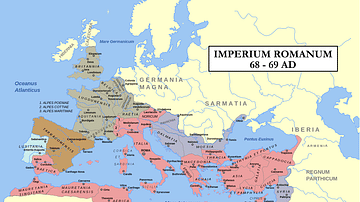

In Imperial times the Emperor took an active role in legal matters, especially in response to private petitions (libelli), but he typically acted on the advice of those best qualified to judge legal matters, namely, the jurists (see below). Perhaps the most famous example of an emperor creating a new law was Caracalla's edict of 212 CE which granted Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. The emperor also acted as a judge when there were conflicts between Roman law and the local law of the provinces, which was generally kept intact and, at least theoretically, the problem was eliminated with Caracalla's edict. In practice local laws survived as customs and were generally not overruled unless they offended Roman sensitivities, for example those concerning incest and polygamy.

From the reign of Hadrian the emperor's judgements and pronouncements were collected into the constitutions of the emperor or constitutiones princips. In addition, the Senate could also issue regulatory provisions (senatus consulta), for example, regarding public games or the inheritance rights of women. Statute law established by the people via public assemblies (comitia), although rare, might also contribute to the legal corpus but was generally limited to ceremonial matters such as deciding on the posthumous honours to be given to the children of emperors who died prematurely.

During the reign of Constantine I the imperial pronouncements often came via the emperor's quaestor and the language used within these became increasingly less technical, an argument often cited as the beginning of the 'vulgarisation' of Roman law. However, in fact law schools actually flourished and legal experts were still on hand both for the quaestor and the public to deliberate on the finer points of law left ambiguous by this new, less technical approach to the wording of legislation.

An important element of Roman law was the jurists (iurisprudentes), legal experts who subjected written laws, rules and institutions to intellectual scrutiny and discussion in order to extract from them the fundamental legal principles they contained and then applied and tested those principles on hypothetical specific cases in order to then apply them to new legislation. The jurists were an elite body as there were probably fewer than 20 at any one time and their qualification for the role was their extensive knowledge of the law and its history. In imperial times they were incorporated within the general bureaucracy which served the emperor. Jurists also had something of a monopoly on legal knowledge as the opportunity to study law as part of the usual educational curriculum was not possible before the mid-2nd century CE. Jurists also wrote legal treatises, one of the most influential was On the Civil Law (De Iure Civili) by Q. Mucius Scaevola in the 1st century BCE.

Whilst jurists often came from the upper echelons of society and they were, perhaps inevitably, concerned with matters of most relevance to that elite, they were also concerned with two basic social principles in their deliberations: fairness (aequitas) and practicality (utilitas). Also, because of their intellectual monopoly, jurists had much more independence from politics and religion than was usually the case in ancient societies. From the 3rd century CE, though, the jurist system was replaced by a more direct intervention by those who governed, especially by the emperor himself. Gradually the number of legal experts proliferated and jurists came to resemble more closely modern lawyers, to be consulted by anyone who needed legal advice. Unlike modern lawyers, though, and at least in principle, they offered their services for free.

Practicalities

In practice litigation was very often avoided by the counterparties swearing an oath or insiurandum but, failing to reach a settlement of this kind, legal proceedings would follow by the plaintiff summoning the defendant to court (civil cases: iudicia publica or for cases in criminal law: quaestiones). The first stage of most legal cases was when the parties involved went before a magistrate who determined the legal issue at hand and either rejected the case as a matter for legal intervention (denegatio actiomis) or nominated an official (iudex datus) to hear and judge the case. When both parties agreed to the magistrate's assessment, the case was heard before the iudex, who made a decision on behalf of the state. Defendant and plaintiff had to represent themselves at the hearing as their was no system of legal representation. If the defendant lost a civil case, there was a condemnatio and they would have to pay a sum of money (litis aestimatio), typically decided by the iudex, which might cover the original value of goods or damages incurred to the claimant.

Penalties for crimes were designed as deterrents rather than corrective measures and could include fines (multae), prison, castigation, confiscation of property, loss of citizenship, exile, forced labour or the death penalty (poena capitis). Penalties might also differ depending on the status of the defendant and if they were male, female, or a slave. Perhaps unsurprisingly, males of higher social status usually received more lenient penalties. The severity of the penalty could also depend on such factors as premeditation, provocation, frequency, and the influence of alcohol.

In many cases, especially civil ones, if a defendant died before proceedings were completed then their heir could be required to stand in the original defendant's place. In the republic there was no real means of appeal in Roman law but in the imperial period dissatisfied parties could appeal to the emperor or high official and the original decision could be quashed or reversed. However, any appeals lacking good grounds could incur a penalty.

Conclusion

Perhaps one of the greatest benefits of Roman law and its legal systems was that, as the empire grew and populations grew more diverse, the law and its protection of citizens acted as a binding force on communities and fostered an expectation that a citizen's rights (and in time even a non-citizen's rights) would be upheld and a system was in place whereby wrongs could be redressed. In addition, the Romans have handed down to us not only many legal terms still-used today in the field of law and legal science but also their passion and expertise for precise and exact legal terminology in order to avoid ambiguity or even misinterpretation of the law, once again, an approach that all modern legal documents attempt to emulate.