The Roman legionary was a well-trained and disciplined foot soldier, fighting as part of a professional well-organized unit, the legion (Latin: legio), established by the Marian Reforms. While major tactical changes appeared during the final days of the Roman Republic and the early days of the Roman Empire, Roman armor and weapons, albeit with minor adaptations, remained simple.

The Roman legionary was equipped with a cuirass, a spear, a sword, a shield, and a helmet. Recruitment was mostly voluntary, although conscription remained an option during emergencies, and military service lasted for 16 years (later extended to 20, then 25). Discipline was severe, and the living conditions were often very harsh. However, the pay was good, and those honorably discharged received a one-time payment and a parcel of land for their service.

Origins

Originally, the Roman army consisted of a citizen militia recruited from the propertied citizenry who served unpaid for the duration of the war. There was a direct link between citizenship, property, and the military. Men from the age of 16 to 46 were eligible to be drafted into the army. Conscription was, and remained, unpopular. The eligible men would be selected via a ballot by each of the existing four legions.

Each soldier had to provide and maintain his own equipment. Fighting in the traditional Greek phalanx formation, the Roman hoplites or foot soldiers (named for their circular shield or hoplon) were essentially heavily-armed spearmen. Their service would end with the Festival of the October Horse on 19 October, signaling the end of the campaign season. The reforms in the 6th century BCE of the sixth king of Rome Servius Tullius brought in a more organized assignment process. Citizens were divided into classes based on wealth. Although recruits still had to be propertied and citizens, they were assigned to maniples by age and experience: hastati, principes, and triari.

Marian Reforms

It was not until the late Republic and the consulship of Gaius Marius (c. 157-86 BCE) and Publius Rutilius Rufus in 107 BCE that the part-time citizen militia became a full-time, professional army. The distinctions between age and experience were abolished. Realizing the need for more soldiers, Marius went against custom and simplified requirements for enlistment, recruiting from the poorer and unpropertied citizens of Rome: the capite censi. Following the Marian Reforms, the legions became more permanent with the Roman government providing all essential equipment: weapons, armor, and clothing. Legionaries would be paid for the days they served and so service in the army became very popular among the poor as it provided food, clothing, better medical facilities, and a steady wage. They benefited not only from the good pay and a possible share of the booty but also from the spoils of war.

All legionaries were considered heavy infantrymen and would be armed alike with a pilum (spear) and a gladius (sword). There was even a guardian of the arms or custos armorum. Each legion was given a standard, either a silver or gold eagle - something that, in time, would instill loyalty in the legionary. In order to reduce the size of the baggage train and increase mobility, each soldier was required to carry his supplies on his back, thereafter known as a “Marius Mule.” Because the old phalanx formation proved ineffective in Roman warfare, it was abandoned. Also among the changes, the cohort replaced the earlier maniple, which now consisted of 480 men divided into six centuries of 80 men. Rufus introduced arms drills and also reformed the process of appointments for senior officers. These new legionaries became better trained, better disciplined, and therefore more flexible and effective in battle.

Augustan Reforms

After coming to power in 27 BCE, Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) totally reformed the army. According to historian Stephen Dando-Collins in his book Legions of Rome, the 1st and early 2nd centuries CE were the golden age of the legion when they "swept all before them." He considered the Roman legion of the imperial era to be a triumph of organization.” He added, "… each component from heavy infantry to cavalry, artillery to supporting auxiliary light infantry, fitting neatly together to form a solid, self-contained military machine" (10).

After his victory against Antonius and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, Augustus wanted to ensure loyalty to him and no one else (namely the Roman Senate). Each soldier was required to take an oath of allegiance to the Roman emperor: the ius iurandum which was renewed every year on 3 January. To accomplish his goal he disbanded 32 of the existing 60 legions thereby discharging 260,000 men. The remaining 28 legions were reduced to 25 when Publius Quinctilius Varus lost 3 legions in the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE.

Later, under emperors Claudius, Nero, Galba, and Trajan, additional legions would be added. In the end, Rome had a standing army of 150,000 legionaries and 180,000 auxiliary infantry and cavalry. Most of the legions were stationed in the troublesome provinces and along the borders. Only nine cohorts remained in Italy, with three of those in Rome.

Recruitment

With the army having become professional and permanent, soldiers were needed to fill the legions. All Roman soldiers were either volunteers or voluntarii who signed on for 16 years (later extended to 20 and then again to 25) or conscripts or lecti. Most were volunteers, however, if necessary, recruits could be obtained through a dilectus. Conscription remained as unpopular in the Empire as it had been in the Republic and was most often used for acquiring auxilia. In Marius' day, failure to report for military service would result in a conscript being declared a traitor and subject to the death penalty. Aside from the changes he made to the legions, Augustus also created a number of specialized troops:

- the Praetorian Guard

- the City Guard or Cohortes urbanae,

- the Night Watch or Vigiles

- the Imperial Bodyguard or German Guard.

In order to fill the army with the necessary legionaries, there was a special recruitment officer or conquisitores. The optimum age for a recruit was between 18 and 23. During the recruitment and interview process, a civilian’s skills were considered and put to good use: blacksmiths became armorers, tailors and cobblers were used to repair uniforms and footwear, while the unskilled were used in a surveyor’s party or the Roman artillery. While a volunteer’s or conscript’s former occupation was important, attention was also paid to his age, height, education, and total fitness. Those who sought to eventually become a centurion had to be able to read and write since all communications (written in Latin) had to be relayed to the legionaries. For the auxilia, potential cavalrymen with good equestrian skills were recruited from former enemies: Roman Gaul, Germania, and Thrace.

In order to prevent a man’s loyalty to become split between the army and his family, a Roman legionary was not permitted to marry until his retirement, and if an individual were married, it would be annulled. The emperor Septimius Severus would suspend this practice in 197 CE. Legionaries were exempt from paying taxes and not subject to civil law. Instead, they were governed solely by military law, which could be extremely harsh. On occasion, during the winter months, furloughs were granted, only if he paid a small fee to the centurion.

Training

There was a long examination and training process before one became a legionary. Before being accepted, all recruits would have their legal status checked. Some came with letters of recommendation which indicated that the individual was free-born and a citizen. Quite often, a letter could lead to rapid promotion. Legal status was important because slaves were not permitted to join the army. If a slave attempted to volunteer, he was subject to the death penalty. If all standards were met during the probation period or probatio, the recruit or tiro would become a signatus and receive his signaculum: a piece of metal worn around the neck in a small leather pouch, signaling the individual’s connection to the military. A signaculum was similar to today’s dog tags and contained important personal information concerning the soldier. Failure to wear one’s signaculum could result in severe punishment. At this time he would take the sacramentum, an oath to the emperor, be given traveling money or viaticum, and attached to a century. Each legion had its own preferred recruiting ground. Upon his arrival at the camp, he would undergo a rigorous training process before officially becoming a Roman legionary.

Training, overseen by a specialized officer or optio, was constant: close-order drills, running great distances while dressed in full armor, and marching in formation and maneuvers. Weapons-training was managed by using wicker shields and wooden swords. There were mock battles, one-on-one combat, and legionaries were expected to rally around the legion’s standard.

Discipline was harsh; centurions carried a vitis or vine cane that was used for beatings, even for minor infractions. In certain situations, the death penalty was authorized if a soldier was found guilty by a military court of tribunes. Eligible offenses included sleeping while on guard duty, stealing, and cowardice. If he was found guilty, the legionary could be crucified or even thrown to wild beasts. There were no appeals. In the time of Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE), when an entire unit was involved in desertion or cowardice, the unit would be sentenced to decimation or reduced by one-tenth. Lots were drawn, and one of every ten would be flogged or stoned to death by the other nine. Rigorous training and harsh discipline made was supposed to ensure obedience without hesitation.

Payment, Awards, & Promotion

Army wages were good. Caesar raised the pay from 450 to 900 sesterces per year, and by the time of Domitian’s reign around 89 CE, it was 1,200 sesterces. Bonuses were possible through individual acts of bravery; however, deductions were also made to cover the legionary’s expenses. There were a number of decorations and awards for outstanding behavior:

- Spear (hasta pura), for wounding an enemy in battle

- Silver Cup, for killing and stripping an enemy in battle

- Silver Standard, for valor in battle

- Torc and Armillae (a golden neckband and wrist bracelet), for outstanding valor in battle

- Gold Crown (corona aurea), also for outstanding bravery in battle

- Mural Crown (corona muralis), for being the first soldier over an enemy’s city wall

- Naval Crown (corona navalis), for bravery in a sea battle;

- Crown of Valor (corona vallaris), for the first soldier to cross the ramparts of an enemy’s camp

- Civic Crown (corona civica), for saving the life of a fellow soldier.

Within the army, there were opportunities for promotion if one had the necessary education and influence. Positions included:

- tesserarius - watch commander responsible for getting the passwords and keeping them safe

- ballistarius - who operated the siege engines

- vexillarius - bearer of the vexillum (the standard of the legion)

- signifer - standard-bearer

- aquilifer - bearer of the eagle standard.

Headquarters also had its share of clerks and orderlies, the beneficiarii who were exempt from normal duties. Lastly, a legionary could always strive to become a centurion, a middle-ranking officer who maintained discipline and considered by some to be the backbone of the army. The centurion (centurio) could be recognized by his silver armor and crested helmet.

Retirement

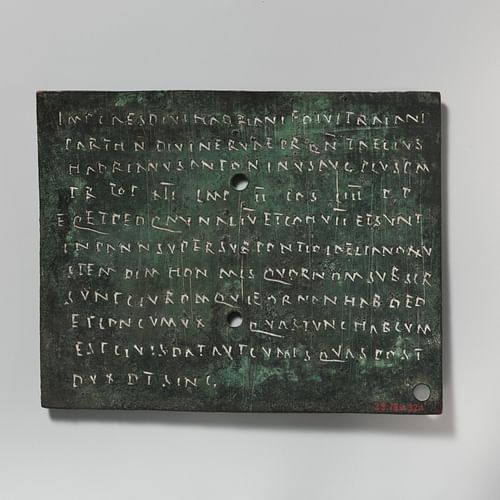

After a legionary's honorable service and discharge, he received the missio honesta. He was issued a statement similar to a diploma indicating his honorable service, a one-time retirement pay (under Augustus it was 12,000 sesterces), and most importantly, land. However, his service did not end there, he could be recalled in an emergency situation to serve as a member of the evocati - retired legionaries returning to service. Those who broke military law were dishonorably discharged, receiving the missio ignominiosa. Others deemed unfit due to mental or physical injury would be given the missio causaria.

Late Roman Empire

During the 4th century CE, major changes were introduced and legionaries now existed as either comitatenses - a mobile strategic reserve at the disposal of the emperor, not tied to any specific region - or limitanei who patrolled the garrisons on the frontier, rarely fighting very far from the forts. Instead of the old Praetorian Guard, which had been disbanded, there were the imperial guard or scholae palatinae and infantry units called the auxilia palatinae. Although the function of the legionary changed over time, they played an important role in the conquest and maintenance of a vast empire that encompassed the Mediterranean Sea.