Roman Nose (Woqini, "Hook Nose", l. c. 1830-1868) was a Northern Cheyenne warrior known for his courage in battle, who became so famous among white settlers and the US military that they believed he was chief of the Cheyenne nation. He was regarded as invincible but was killed at the Battle of Beecher Island.

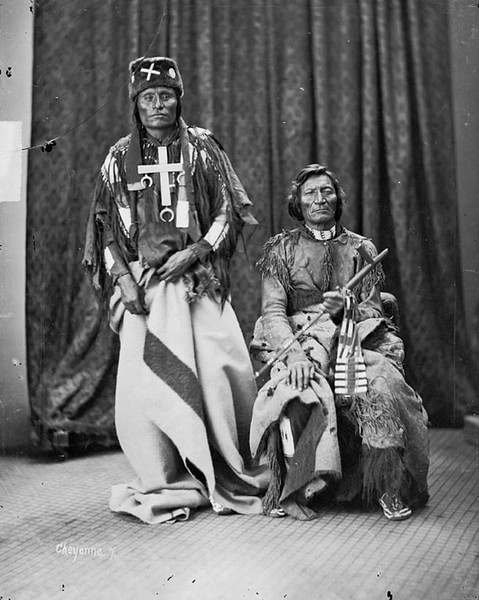

His name, Woqini, translated as "Hook Nose", was misinterpreted by Euro-American writers as "Roman Nose", the name by which he became known even by Native American writers such as the Sioux author and physician, Charles A. Eastman (l. 1858-1939), who included him in his book Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains (1916). Eastman also references him as a "chief", which is often understood to mean a leader of a Native American nation, but Roman Nose was never a chief as he could not tolerate long discussions in councils and preferred action in battle.

He is often confused with the Southern Cheyenne Chief Henry Roman Nose (l. 1856-1917), who fought in the Red River War in 1874 as a young man and was later detained at Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida, but Roman Nose/Hook Nose was already dead by the time Henry Roman Nose was an active warrior. After the Sand Creek Massacre of 29 November 1864, when US cavalry slaughtered over 150 Cheyenne and Arapaho, mostly women, children, and the elderly, Roman Nose swore enmity with the United States. He led war parties against the US forces of the Powder River Expedition (1865) and against white settlers on the Oregon Trail during Red Cloud's War (1866-1868) before dying at the Battle of Beecher Island in 1868.

Although he is not as well known today as his contemporaries such as Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909), Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877), Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890), or Black Kettle (l. c. 1803-1868), Roman Nose was as famous as any of them in his time and is still regarded as a great Native American hero, especially among the Northern Cheyenne.

Early Raids & Sand Creek Massacre

Roman Nose's date of birth is alternately given as early as c. 1823, c. 1830, or c. 1835, and nothing is known of his youth except that he was known as "Bat" and seems to have been notoriously restless and impatient with needless talk. He was tall for his age and is described as standing at over six feet (182 cm) at maturity. He participated in raids against other Native American nations with the military societies of the Cheyenne, including the Dog Soldiers, but certainly the Elk Warriors Society, and, although frequently referenced as a "chief" by the Euro-American press, never sat on the Council of the Forty-Four, which included four chiefs from each of the ten tribes plus four chiefs who had previously served. Roman Nose was always a military commander, never an administrator.

He is famously described as a "chief", however, by the US army surgeon Isaac Coates in 1867, which encouraged the popular notion that he was the leader of the Cheyenne nation and not just a war chief:

Of all the chiefs, Roman Nose attracted the most attention. He is one of the finest specimens, physically, of his race. He is quite six feet in height, finely formed with a large body and muscular limbs. His appearance was decidedly military and, on this occasion, particularly so since he wore the uniform of a general in the army. A seven-shooting Spencer carbine hung at the side of his saddle, four large navy revolvers stuck in his belt, and a bow, already strung with arrows, was grasped in his left hand. Thus armed and mounted on a fine horse, he was a good representative of the God of War. (64)

The Cheyenne had initially tried to stay out of the way of the white settlers as much as possible, but, beginning in 1825, they were increasingly deprived of their traditional hunting grounds. The cholera outbreak of 1849, brought to the region by white settlers, greatly reduced the Cheyenne population as did periodic clashes with immigrants. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 carefully divided up the lands the Plains Indians had always regulated on their own, refusing to recognize any rights of ownership to traditional territories, only right of occupancy, but still stipulated that "Indian territories" were beyond any US claims.

The so-called Cheyenne Uprising of 1863 was a direct response to the US government ignoring yet another treaty and further bullying and land theft. In March of 1863, a delegation of chiefs representing the concerns of Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Caddo, and Kiowa nations went to Washington, D.C., to meet with President Abraham Lincoln to discuss broken treaties, poor treatment by US officials, and to find some means of peaceful resolution to mounting tensions. Nothing was resolved, however, and the members of the delegation were sent home with peace medals and words of encouragement in taking up a sedentary, agricultural lifestyle.

Throughout 1863-1864, US army forces continually made unprovoked attacks on Cheyenne (and other) villages, sometimes claiming they were responding to the theft of livestock. On 16 May 1864, US cavalry rode on the village of the Cheyenne chief Lean Bear, who had been one of the "peace chiefs" to visit Washington, D.C., destroying the lodges and killing the citizens, including Lean Bear, who was still wearing his peace medal.

The year of violence culminated in the Sand Creek Massacre of 29 November 1864 when cavalry under John Chivington attacked Chief Black Kettle's village, which was flying both the white flag of truce and the American flag, and massacred approximately 150 Cheyenne and Arapaho. The Dog Soldiers, especially, but the other Cheyenne military societies also, now claimed the peace overtures made by the Council of Forty-Four were misguided and the only way to protect the people and preserve their land was war. Roman Nose, possibly with the Elk Warriors Society at this time, was among those advocating for armed resistance to the United States' genocidal policies.

Powder River Expedition & Red Cloud's War

After the Sand Creek Massacre, Roman Nose begins appearing in Euro-American periodicals as a "Cheyenne Chief" who always led his warriors from the front. In 1865, the US launched the Powder River Expedition which was supposed to 'deal with the Indian problem' decisively by subduing the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux – who were among those considered 'hostile' – and make the region safe for white settlers. Roman Nose led several war parties against US forces including at the Battle of the Platte Bridge (26 July 1865) along with Crazy Horse, Red Cloud, and Morning Star (also known as Dull Knife, l. c. 1810-1883).

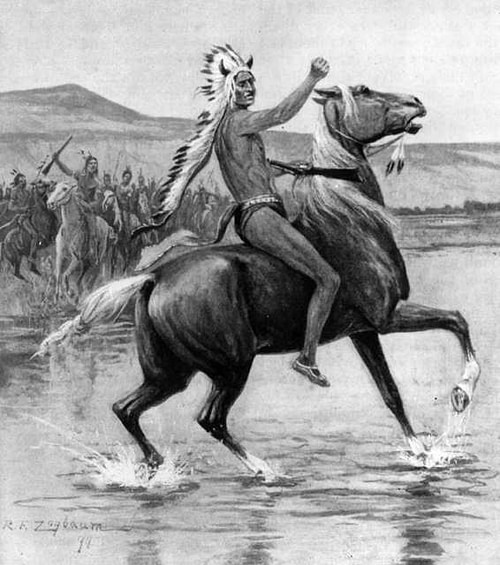

This engagement was a Native American victory as was the Battle of Red Buttes, happening at the same time, in which Roman Nose presented himself as a target, riding swiftly around the corral of wagons, until the soldiers had used up all their ammunition and were quickly slaughtered. On 8 September 1865, Roman Nose and Crazy Horse attacked the forces under Colonel Cole and Lt. Colonel Walker on the Powder River using the same tactics but, this time, the US forces were armed with Spencer carbine repeating rifles and more ammunition, making for a much harder fight. Still, Roman Nose tried to rally his warriors and intimidate the enemy just as he had at Red Buttes and the Platte Bridge, as described by scholars Bob Drury and Tom Clavin:

Roman Nose spurred his white pony across the dusty no-man's land with its clumps of sedge and needle grass. His eagle war bonnet trailed the ground as he raced from one end of the American position to the other, screaming insults and bellowing challenges. Again, the solders stayed put. The Cheyenne managed three rushes before his horse was shot and killed. At this, the combined tribal force charged the corral en masse. They were repelled by whistling grapeshot and the crackling reports of hundreds of Spencer carbines. (215-216)

The Powder River Expedition accomplished nothing except to confirm what Roman Nose, Crazy Horse, and others already knew: that the US government could not be trusted and the only option open to the Plains Indians was war. In 1866, when Colonel Henry B. Carrington arrived in the region with his troops and a mandate to build forts to protect white settlers, Red Cloud declared war. Although Roman Nose was not a part of Red Cloud's war party, he worked toward the same end by attacking supply wagons and white settlers on the Oregon Trail and elsewhere.

Eastman's Profile

Charles A. Eastman provides one of the most famous descriptions of Roman Nose which he wrote based on legends he had heard as he was only ten years old when Roman Nose was killed at Beecher Island. Although the description is idealized at points, it does accurately represent how Roman Nose was seen by others. The following passage comes from Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains:

This Cheyenne war chief was a contemporary of Dull Knife. He was not so strong a character as the other and was inclined to be pompous and boastful, but with all this, he was a true type of Native American in spirit and bravery.

While Dull Knife was noted in warfare among Indians, Roman Nose made his record against whites in defense of territory embracing the Republican and Arickaree rivers. He was killed on the latter river in 1868 in the celebrated battle with General Forsythe.

Save Chief Gall [Hunkpapa Sioux, l. c. 1840-1894] and Washakie [Shoshone chief, l. c. 1804/1810-1900] in the prime of their manhood, this chief had no peer in bodily perfection and masterful personality. No Greek or Roman gymnast was ever a finer model of physical beauty and power.

He thrilled his men to frenzied action when he came upon the field. It was said of him that he sacrificed more youths by his influence in battle than any other leader, being very reckless himself in grandstand charges. He was killed needlessly in this manner.

Roman Nose always rode an uncommonly fine, spirited horse, and with his war bonnet and other paraphernalia, gave a wonderful exhibition. The Indians said that the soldiers must gaze at him rather than aim at him, as they seldom hit him even when running the gauntlet before a firing line.

He did a remarkable thing once, when on a one-arrow-to-kill buffalo hunt, with his brother-in-law. His companion had selected his animal and drew so powerfully on his sinew bowstring that it broke. Roman Nose had killed his cow and was whipping up close to the other when the misfortune occurred. Both horses were going at full speed, and the arrow jerked up in the air. Roman Nose caught it and shot the cow for him.

Another curious story told of him is that he had an intimate Sioux friend who was courting a Cheyenne girl, but without success. As the wooing of both Sioux and Cheyenne was pretty much all affected in the nighttime, Roman Nose told his friend to let him do the courting for him. He arranged with the young woman to elope the next night and spend the honeymoon among his Sioux friends. He then told his friend what to do. The Sioux followed instruction and carried off the Cheyenne maid, and not until morning did she discover her mistake. It is said she never admitted it and that the two lived happily together to a good old age, so perhaps there was no mistake after all.

Perhaps no other chief attacked more emigrants going west on the Oregon Trail between 1860 and 1868. He once attacked a large party of Mormons, and in this instance, the Mormons had time to form a corral with their wagons and shelter their women, children, and horses. The men stood outside and met the Indians with well-aimed volleys, but they circled the wagons with whirlwind speed, and whenever a white man fell, it was the signal for Roman Nose to charge and count the "coup." The hat of one of the dead men was off, and although he had heavy hair and beard, the top of his head was bald from the forehead up. As custom required such a deed to be announced on the spot, the chief yelled at the top of his voice: "Your Roman Nose has counted the first coup on the longest-faced white man who was ever killed!"

When the Northern Cheyenne, under this daring leader, attacked a body of scouting troops under the brilliant officer General Forsythe, Roman Nose thought he had a comparatively easy task. The first onset failed, and the command entrenched itself on a little island. The wily chief thought he could stampede them and urged on his braves with the declaration that the first to reach the island should be entitled to wear a trailing war bonnet. Nevertheless, he was disappointed, and his men received such a warm reception that none succeeded in reaching it. To inspire them to desperate deeds, he had led them in person, and with him, that meant victory or death. According to the army accounts, it was a thrilling moment and might well have proved disastrous to the Forsythe command, whose leader was wounded and helpless. The danger was acute until Roman Nose fell, and even then, his lieutenants were bent upon crossing at any cost, but some of the older chiefs prevailed upon them to withdraw.

Thus, the brilliant war chief of the Cheyenne came to his death. If he had lived until 1876, Sitting Bull would have had another bold ally.

(189-190)

Medicine, Ritual & Beecher Island

Roman Nose's invincibility was attributed to his "medicine" – his personal spiritual power – which was awakened through rituals performed prior to battle and maintained by his headdress – made for him by the medicine man White Bull – which he believed made him bulletproof. The war bonnet/headdress was so long, and adorned with so many eagle feathers, that it almost touched the earth when he sat astride his horse. In order for the "medicine" to be effective, however, he needed to avoid shaking hands with anyone or eating anything cooked in a metal pot or served to him with a metal implement – both associated with white people who failed to keep their promises.

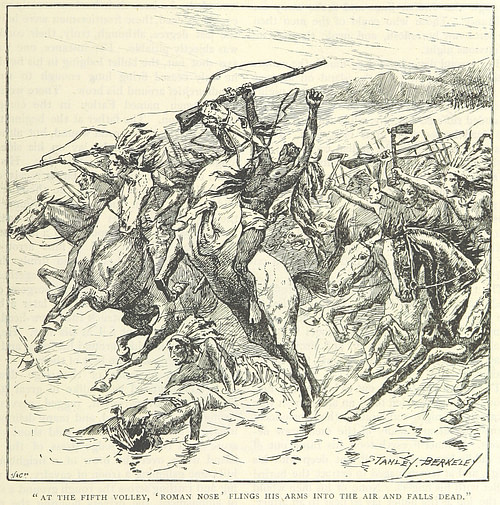

According to Cheyenne lore, it was his failure to honor these taboos that led to his death. Roman Nose had been running the gauntlet in front of US troops for over eight years when he led his warriors against General Alexander Forsyth (l. 1837-1915) at Beecher Island (not to be confused with James W. Forsyth, responsible for the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890). Roman Nose recognized he had eaten a piece of fry bread cooked in an iron pot and served to him by a metal fork and was in the process of ritually cleansing himself when the fighting broke out. Another Cheyenne warrior, sometimes identified as White Contrary, mocked him for remaining safely behind a hill performing magic while he'd sent his warriors into the hail of Forsyth's gunfire and so Roman Nose stopped the ritual and, knowing he would die, joined the fight.

He led the warriors in another charge against Forsyth's position and was shot in the back as he wheeled about; he fell from his horse mortally wounded, dying later on 17 September 1868. As Eastman notes, his warriors wanted to continue the battle, and they did for two more days before withdrawing. They honored Roman Nose with proper funerary rites and placed his body on a scaffold – as they did with the other casualties of the engagement known to the Cheyenne as "The Fight Where Roman Nose Was Killed" – but all of these were knocked down and the bodies desecrated by the US cavalry who returned months later to recover the remains of the Forsyth command.

Conclusion

The death of Roman Nose was the beginning of the end of Cheyenne resistance to US Westward Expansion. Although Red Cloud had won his war, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 was not honored by the United States, and, on 27 November 1868, Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer attacked Chief Black Kettle's camp at the Battle of Washita River, murdering upwards of 100 people, mostly women, the elderly, and children, along with Black Kettle and his wife.

The Cheyenne Dog Soldiers under Chief Tall Bull (l. 1830-1869) continued their resistance until his defeat and death at the Battle of Summit Springs on 11 July 1869. The Cheyenne and Arapaho joined with the Sioux under Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, which was a decisive Native American victory, but reprisals by the US army afterwards and the loss of the buffalo – systematically slaughtered by US agents to deprive the Plains Indians of their food supply – eventually drove the Cheyenne into the "Indian Territory" the US government had reserved for them in modern-day Oklahoma.

Today, the Northern Cheyenne of Roman Nose live on the reservation in Montana and the Southern Cheyenne remain in Oklahoma. The site of "The Fight Where Roman Nose Was Killed" was named Beecher Island in honor of one of the US scouts of Forsyth's command, Fred Beecher, who died in the engagement. A monument was raised to honor the US cavalry casualties in 1905 on land Roman Nose died defending and that the US government had declared, in 1851, they had no claim to.