The Roman Senate functioned as an advisory body to Rome's magistrates and was composed of the city's most experienced public servants and society's elite. Its decisions carried great weight, even if these were not always converted into laws in practice. The Senate continued to exert influence on government in the imperial period, albeit to a lesser degree.

Over time the Senate witnessed an increase in the army's intervention in politics and suffered manipulation in both membership and sessions by successive emperors. The institution outlasted all emperors, and senators remained Rome's most powerful political movers, holding key public offices, influencing public opinion, commanding legions, and governing provinces.

Origins

The Romans used the name senatus for their most important seat of government, which derives from senex meaning 'old' and meant 'assembly of old men' with a connotation of wisdom and experience. Members were sometimes referred to as 'fathers' or patres, and so this combination of ideas illustrates that the Senate was a body designed to provide reasoned and balanced guidance to the Roman state and its people.

According to tradition, Rome's founder Romulus created the first 100-member Senate as an advisory body to the sovereign, but very little is know about its actual role in Rome's early history as a monarchy. In the early Republic, it is likely the body began as an advisory board to magistrates and then grew in power as retired magistrates joined it as indicated by the lex Ovinia (after 339 BCE but before 318 BCE) which set out that members should be recruited from the 'best men.' A new list of members was compiled every five years by the censors, but senators usually kept their role for life unless they had committed a dishonourable act. For example, in 70 BCE, no fewer than 64 senators were omitted from the new list for undignified conduct. The system was now in place which, in effect, created a new and powerful political class that would dominate Roman government for centuries.

Membership

From the 3rd century BCE there were 300 members of the Senate, and after the reforms of Sulla in 81 BCE, there were probably around 500 senators, although after that date there does not seem to have been either a specific minimum or maximum number. Julius Caesar instigated reforms in the mid-1st century BCE, gave out membership to his supporters, and extended it to include important individuals from cities other than Rome so that there were then 900 senators. Augustus subsequently reduced the membership to around 600. The senators were led by the princeps senatus, who always spoke first in debates. The position became less important in the final years of the Republic, but it was brought back to prominence under Augustus.

There is evidence that the Senate was not wholly composed of members of the aristocratic patrician class, even if they formed the majority of its members. Some non-senators - magistrates of certain kinds such as tribunes, aediles and later quaestors - could attend and speak in sessions of the Senate. Invariably, such members were made full senators in the next censorship. Naturally, not all members actively participated in sessions and many would simply have listened to the speeches and voted.

The rank of senator carried with it certain privileges such as the right to wear a toga with a Tyrian purple stripe (latus clavus), a senatorial ring, special shoes, an epithet (later with three ranks: clarissimi, spectabiles, illustres), certain fiscal benefits, and the best seats at public festivals and games. There were restrictions too, with no senator being able to leave Italy without the Senate's approval, own large ships, or bid for state contracts.

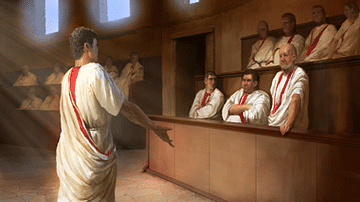

The Curia

The Senate met in various places in Rome or its outskirts within a mile of the city boundary, but the place had to be sacred, that is a templum. The obvious candidate was a temple, but the Senate most commonly met in the Curia, a public building in Rome. The first was the Curia Hostilia, used in the early kingdom, then the Curia Cornelia, built by Sulla, and finally the Curia Julia, built by Caesar, finished by Augustus and used thereafter. The sessions were open to the public with a literal open door policy that allowed people to sit outside and listen in if they wished.

Legislation & Proceedings

The formal function of the Senate was to advise the magistrates (consuls, censors, quaestors, aediles, and so on) with decrees and resolutions. Its decisions were given further weight by the fact that many senators were themselves ex-magistrates with practical experience of governance, and so, in practice, vetoes were rare (but did occur by, for example, the tribunes of the popular assembly, the tribuni plebis). Magistrates also had to consider that they would themselves be back in the Senate after their one year of office. Upon implementation the decrees became law. Exceptionally, during the crises presented by the fall of the Republic, the Senate could and did issue emergency decrees (senatus consultum ultimum) it deemed necessary to protect the state.

From the 4th century BCE, the Senate became increasingly influential on public policy as that of the popular assemblies and magistrates waned. The Senate decided on such matters as domestic policies, including financial and religious areas, first formulating proposals which only then did the popular assemblies have the opportunity to debate. Foreign policy was also considered such as hearing foreign ambassadors, deciding the distribution of the legions, and creating provinces and deciding their borders. Existing laws and their deficiencies could also be debated. In addition, the Senate had the power to shine prestige on Rome's most powerful men, notably in the award of triumphs for successful military campaigns.

A record was kept of the proceedings (senatus consulta) and published for the public to consult in the public archive or Tabularium. The practice was stopped by Augustus. Senators could always access these records, though, and writers, who were almost always senators, were not shy to quote from them in their works.

The Imperial Period

The Senate was still an influential body even after Augustus became emperor. Senators continued to debate and sometimes disapprove of the emperor's actions, and as the historian F.Santangelo notes, the Senate "retained important prerogatives in military, fiscal, and religious matters, and appointed the governors of the provinces that were not under the direct control of Augustus" (Bagnall, 6142). Certain law cases involving non-senators as well as senators (e.g. bribery, extortion, and crimes against the people) were decided by the Senate and their ruling could not be overturned by the emperor.

The Senate remained a prestigious body with important ceremonial and symbolic powers, membership of which was still the aspiration of Rome's elite citizens, now accessible to new members only via election to the quaestorship (20 per year). Augustus introduced a minimum property qualification for membership and then created a senatorial order whereby only sons of senators or those given the status by the emperor could become senators. Over the centuries, as the empire expanded so too did the geographical origins of the senators until, by the 3rd century CE, up to 50% of senators came from outside Italy.

In practice, despite their continued influence and prestige, the senators' powers had greatly diminished compared to in the Republic at its height. A small group of senators was now appointed by the emperor (consilium) which decided what exactly would be debated by the full Senate, which Augustus himself sometimes chaired in person. Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE) was another keen attendee, but he dispensed with the consilium, even if many subsequent emperors formed a similar informal advisory panel which included some senators. Real political power was in the hands of the emperors, but the Senate, nevertheless, continued to pass a large quantity of legislation during the Principate. Another important influence was the speeches made by senators, but when emperors started to make these themselves (orationes), they were subsequently quoted by jurists, suggesting they may have had, in practical terms, the force of law. Augustus also set a time limit on speeches made by anyone except the emperor. The Senate might have become less influential, but emperors were still formally given their power of office by it, and therefore their legitimacy to rule. The Senate could also have the ultimate last word on an emperor's reign by declaring them a public enemy or officially erasing their memory (damnatio memoriae).

Threats to the Senate

There were direct challenges to the authority of the Senate besides those arising from Rome's everyday system of government. In the 70s BCE a rival body was set up in Spain by Sertorius and the Senate itself was often split into factions during the death throes of the Republic when large groups of senators sided with the most powerful men of the time such as Marius, Pompey, and Caesar. A great many senators also fell foul of the political machinations of these men of ambition and were expelled from the Senate or worse.

Throughout the imperial period most emperors recognised that the Senate was an important voice of the elite of Rome and a reflection of their necessary involvement in the functioning of the empire, but their very attendance, the importance given to imperial speeches, and the moving away from acclamation instead of actual voting to pass legislation suggests that the Senate steadily declined as a forum of genuine political debate.

Reforms by Diocletian (284-305 CE) and Constantine (306-337 CE) transferred many public positions from the senators to the equestrians or at least blurred the distinction between the two classes. The Late Empire then saw the momentous decision to split the Senate into two bodies, one in Rome and the other in Constantinople. As the emperor now resided in the latter city, the Senate of Rome became only concerned with local matters. The Senate continued on, though, and even outlasted the Roman Empire itself, but it would never regain the power and prestige it had enjoyed in the middle centuries of the Republic before Rome became dominated by individuals of vast wealth and military power.