Roman warfare was remarkably successful over many centuries and across many territories. This was due to several important factors. Italy was a peninsula not easily attacked, there was a huge pool of fighting men to draw upon, a disciplined and innovative army, a centralised command and line of supply, expert engineers, and effective diplomacy through a network of allies.

Further, Rome’s allies not only supplied, equipped and paid for additional men but they also supplied vital materials such as grain and ships. In addition, the Romans had an inclusive approach to conquered peoples which allowed for the strengthening and broadening of the Roman power and logistical bases. On top of all this, Rome was more or less in a continuous state of war or readiness for it and believed absolutely in the necessity of defending and imposing on others what she firmly believed was her cultural superiority.

Ready For War

In Roman culture martial values were highly regarded and war was a source of prestige for the ruling class where career progression came from successful military endeavour. Indeed, conflict in Roman culture went right back to the origins of Rome and the mythical battle between Romulus and Remus. This thirst for war combined with what Polybius stated as 'inexhaustible resources in supplies and men' meant that Rome would become a terrible and formidable foe for the peoples of the Mediterranean and beyond. However, there were also times when Romans more than met their match - such as against Carthage, Parthia and the Germanic tribes - or when Romans fought Romans such as the civil wars between Julius Caesar and Pompey or Vitellius against Otho, and then the carnage of ancient warfare reached even greater proportions.

In the Republic declaration of war was in theory in the hands of the people but in practice the decision to raise arms was decided by the Senate. From Augustus onwards the decision became the Emperor's alone. Once military action was decided upon certain rituals had to be performed such as sacrifices and divination to find favourable omens and the supplicatio rite where prayers and offerings were offered at each of the major gods' temples.

Structure & Command of the Roman Army

The Roman army left its mark wherever it went, creating roads, depots and bases. Involving men from the age of 16 to 60, it was a conduit for the Romanisation of conquered lands and one of the main carriers of foreign cultural influence back on Rome itself.

Either or both of the two consuls conducted war on the battlefield although command could also rest in the hands of a praetor or pro-magistrate with imperium who, otherwise, commanded individual legions. If both consuls were present they rotated command each day. In the Imperial period the emperor himself could lead the army. Tribunes and Legates could also command a legion or subsidiary detachments and each maniple of 200 men was commanded by a prior and posterior centurion (the former being senior), resulting in around 60 centurions per legion.

In the early Republican period troop formation followed the example of the Greek phalanx but from the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century BCE the tactics for infantry deployment changed. The largest unit in the Roman army was the legion of 4,200 men divided into 30 divisions or maniples which were now each deployed in three lines (hastati, principes, and triarii who were the veterans) arranged as in a checkerboard (quincunx). Another 800 to 1200 light-armed soldiers (velites), often from Rome's allies, took position in front of the legion with 300 cavalry positioned in support. These two groups were used as a protective screen for the heavy infantry legions and they also harried the enemy from the flanks when the enemy met the legions head on. In the 1st century BCE both disappeared from the army but the cavalry did make a comeback in the Imperial period. Specialist mercenary troops with skills the Romans lacked might also be employed such as Cretan archers and slingers from Rhodes.

The maniples were mobile, disciplined in their close formation and they could rotate their engagement with the enemy to allow fresh troops into the battle. Manoeuvrability was also aided by the adoption of lighter weaponry - the short sword or gladius Hispaniensis, the pilum javelin instead of the traditional heavy spear, and the central-handled, concave shield or scutum. In addition, it came to be recognised that terrain could be an important factor in aiding or hindering troop movements. Troops were also trained to use these weapons well and to carry out complicated battle manoeuvres, although the duration and intensity of training was very much down to individual commanders.

From 100 BCE (or perhaps even earlier) the maniple was abandoned and instead a legion was divided into 10 cohorts of 4-500 men which would remain the basic Roman tactical unit. In this period, legions also took on permanent names and identities and were equipped by the state. In 167 BCE there were 8 legions but by 50 BCE this number had risen to around 15 legions. Augustus in c. 31 BCE created for the first time a permanent and fully professional army with a central command and logistics structure resulting in a permanent force of 300,000 men paving the way for the huge armies of later centuries when there were 25-30 legions across the empire. In 6 CE the emperor also created a treasury specifically for the military (aerarium militare) which was funded by taxes and allowed for a system of retirement benefits. Another of Augustus' policies was to ensure loyalty by carefully restricting positions of command to the Imperial clique.

Motivating the Troops

All troops swore an oath of allegiance, the sacramentum, to the emperor himself. This was a major factor in ensuring loyalty but it also encouraged the discipline - disciplina militaris - for which the Roman armed forces had become famous since the early Republic and which was directly responsible for many a victory on the battlefield. Discipline was further ensured through a system of rewards and punishments. Soldiers could receive distinctions, money, booty, and promotion for displaying courage and initiative. However, a lack of rewards and excessively long service without leave could cause grievances which sometimes developed into mutiny. Punishment came in many forms and could be implemented due to mutinous dissent but also a lack of courage in battle. In particular, the punishment of decimation was usually reserved for cowardice, for example, abandoning the body of a fallen commander. This involved lots being drawn and every tenth man being clubbed to death by the other nine. Other punishments included loss of booty, pay or rank, flogging, dishonourable discharge, being sold into slavery or even execution. The principle was that by breaking one's oath of allegiance, one lost all of one's rights.

Strategies

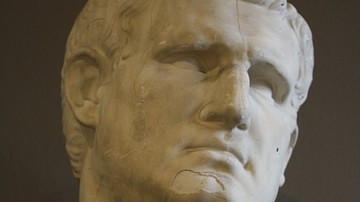

Julius Caesar's Commentaries on the Gallic War describes the great commander's attention to logistics, decisiveness and appearance of confidence and their positive effect on the morale of the troops. He also records the importance of innovation, patriotism, discipline and fortune. In addition, a commander could greatly strengthen his chances of success before the battle by gathering military intelligence of the enemy from captives, dissenters and deserters. Commanders could hold (as Caesar himself did) a consilium or war council with their officers to present and discuss strategies for attack and utilise the experience of veteran campaigners. It would be a combination of all of these factors that would ensure Roman military dominance for centuries. There were important defeats along the way but it is interesting to observe that commanders often escaped repercussions for their military incompetence and it was usually the soldiers who bore the blame for defeat.

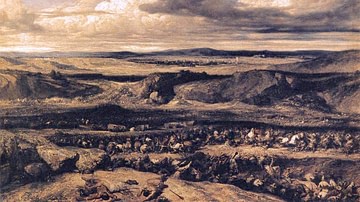

Roman commanders generally preferred an aggressive and full-frontal attack (albeit preceded by suitable reconnaissance by a scouting vanguard of exploratores troops) whilst terror and revenge tactics were also used to subdue local populations, a strategy mixed with clementia - accepting hostages and promises of peace from the enemy. From the 1st century BCE there was an increase in the use of battlefield fortifications and entrenchments and sieges. From the 3rd century CE defence of the empire's borders became a priority and led to the fortification of cities and a more mobile deployment of smaller units of troops (vexillationes) of between 500 and 1,000 men. This was largely due to enemy forces being wary of full-on attacks with the formidable Romans and so preferring guerrilla tactics. Julius Caesar was also a great proponent of sieges and they did present certain advantages. An opposing force could be severely reduced in one blow, the local population could be suitably terrorised into accepting Rome as their new master and a readymade stronghold could be acquired if successful.

Sieges

In a typical siege forces were sent ahead to surround the settlement to be attacked and prevent anyone escaping. The main force would build a fortified camp out of missile range from the city and preferably on high ground, which provided a good vantage point to observe inside the settlement and pick out key targets such as water supply. Once the attack began, the defender's walls could be overcome by building a ramp up against them using trees, earth and rocks. Whilst this was being done the attackers would be protected by temporary covers and a covering fire from batteries of torsion catapults, bolt-firers, stone-throwers and archers. The defenders could try to extend the height of the wall section under attack and even add towers. The attackers could also attack the walls with heavy rams (suspended on a framework) and also use siege towers. The defenders threw everything they could down on the attackers such as burning oil, burning pieces of wood and rocks and they could also try to undermine the siege ramps and towers by tunnelling, a technique the attackers might also employ to undermine the defensive walls. Generally, once conquered, only the women and children could hope to survive as an example had to be set of the futility of prolonged resistance.

Logistics

The Imperial army on the march was first and foremost well-ordered. Besides legionaries, the troop could include cavalry, archers, auxiliaries, artillery, rams, standard bearers, trumpeters, servants, baggage mules, blacksmiths, engineers, surveyors, and road builders. When the army reached its destination it made a fortified camp and the logistical skills of the Romans meant that they could be supplied independent of the local territory, especially in terms of food. Once supplies had reached a camp they were stored in purpose-built warehouse (horrea) which, constructed on stilts and well ventilated, better preserved perishable goods. Food stores were protected against their number one enemy - the black rat - by using cats, which were, for the same reason, also used on ships.

One particular innovation of the Imperial period was the introduction of doctors (medici) and medical assistants (capsarii), who were attached to most military units. There were even army hospitals (valetudinarium) within the fortified camps.

Naval Warfare

Roman naval tactics differed little from the methods employed by the Greeks. Vessels were propelled by rowers and sail to transport troops and in naval battles the vessels became battering rams using their bronze-wrapped rams fixed on the ship's prow. Rome had employed naval vessels from the early Republic but it was in 260 BCE that they built their first significant navy, a fleet of 100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes, in response to the threat from Carthage. Quinqueremes, with five banks of rowers, were fitted with a bridge used to hold enemy vessels so that they could be boarded, a device known as the corvus (raven). The Romans eventually defeated the Carthaginian fleet, largely because they were able to replace lost ships and men quicker. Rome once more amassed a fleet when Pompey attacked Pamphylia and Cilicia in 67 BCE (a campaign identified with the suppression of piracy by Plutarch) and again in 36 BCE when Marcus Agrippa amassed almost 400 vessels to attack Sicily and the fleet of Sextus Pompeius Magnus. Some of Agrippa's ships had the new grappling hook launched by a catapult which, with a winch, was used to draw in an enemy ship for boarding.

In 31 BCE there occurred the major naval battle near Actium between the fleets of Octavian and Mark Antony and Cleopatra. Following victory, the new emperor Augustus established two fleets - the classis Ravennatium based at Ravenna and the classis Misenatium based at Misenum, which operated until the 4th century CE. There were also fleets based at Alexandria, Antioch, Rhodes, Sicily, Libya and Britain as well as one operating on the Rhine and another two on the Danube. These fleets allowed Rome to quickly respond to any military needs throughout the empire and to supply the army in its various campaigns.

Fleets were commanded by a prefect (praefectus) appointed by the emperor. The captain of a vessel held centurion rank or the title of trierarchus. Fleets were based at fortified ports such as Portus Julius in Campania which included artificial harbours and lagoons connected by tunnels. Crews of Roman military vessels were, in reality, more soldiers than sailors as they were expected to act as light-armed land troops when necessary. They were typically recruited locally and drawn from the poorer classes but could also include prisoners of war and slaves.

Victor's Spoils

Victory in battle brought new territory, acquired wealth and resources, persuaded enemies to sue for peace and sent a clear message that Rome would defend her frontiers, that she had an insatiable thirst for expansion and provided irrefutable evidence of just how formidable a fighting machine the Romans could present on the battlefield.

In the Republic enemy arms could be burned and offerings made to the gods, especially Mars, Minerva and Vulcan. Victorious commanders returned to Rome as heroes in a grand triumphal procession and there were over 300 of them over the centuries. The triumph was first approved and paid for by the Senate. The commander entered the city riding a chariot in a sumptuous procession which included captives, treasures such as gold and works of art, and even exotic animals from the territory of the victory. He wore purple robes (toga picta and tunica palmata) and a crown of laurel, held an ivory sceptre and laurel branch and had a slave standing behind him who held a gold crown over his head and whispered, 'Look behind' (Respice) to remind him of the dangers of pride and arrogance. From the Augustan period only emperors could enjoy a triumph but, in any case, the practice became much less frequent.

Victorious commanders also used the spoils of war to beautify Rome, for example, Pompey's theatre, Augustus' forum and Vespasian's Colosseum. Other architectural celebrations of victory included obelisks and columns but perhaps the most striking monument to Roman military vanity was the triumphal arch, the largest and most decorative being that of Constantine I in Rome.

Conclusion

Rome's armed forces were the state's largest single expense but the captured territory, resources, wealth and slaves and the later necessity for frontier defence meant that war was an unavoidable Roman preoccupation. Great successes in battle could be enjoyed but so too, defeats could rock Rome to its foundations as able opponents began to use Rome's winning strategies to their own advantage. Further, as Rome's military prowess became more and more well known it would become increasingly difficult for the Roman military to directly engage the enemy. However, over many centuries and across three continents, the Romans had demonstrated that a well-trained, well-disciplined military, if fully exploited by gifted commanders, could reap vast rewards and it would not be until a millennium after its fall that warfare would return to the scale and professionalism that Rome had brought to the field of combat.