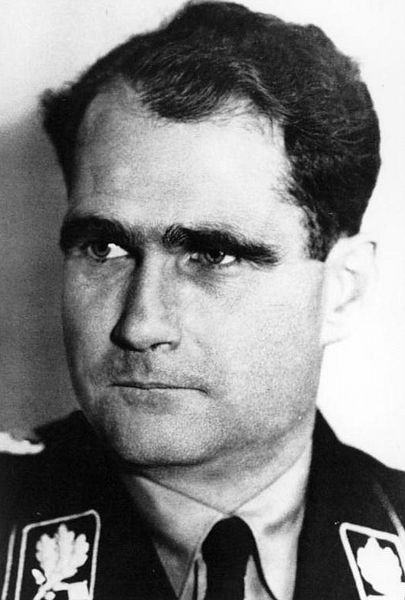

Rudolf Hess (1894-1987) was deputy leader of the German Nazi Party and a key figure in the fascist regime of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) until his bizarre decision in 1941 to fly to Scotland. Hess believed he could persuade Britain to withdraw from the Second World War (1939-45), which would allow Germany to concentrate on fighting the USSR.

Hess's diplomatic overtures were dismissed as nonsense by both the British government and Hitler. Hess had acted without Hitler's blessing, and he was shunned as a lunatic. Hess remained a prisoner, first in Britain and then, after he was found guilty at the Nuremberg Trials, in Germany. He committed suicide at the age of 93, although his physical frailty led to some speculation as to just how he had managed to hang himself in the garden of Spandau prison.

Early Life

Rudolf Richard Hess was born in Alexandria, Egypt, on 26 April 1894. Rudolf's father owned a successful export company in the port city, but he insisted his son study in Germany from the age of 14. Rudolf then worked in his father's business until the outbreak of the First World War (1914-18) when he enlisted as a volunteer. Hess joined the same regiment in the Bavarian army that Adolf Hitler served in, the 1st Bavarian Infantry Regiment. He won his commission, the rank of lieutenant, but after being twice wounded and winning the Iron Cross Second Class medal, he decided to join the German Air Force, although the war ended just a few months later.

Hess moved to Munich, where he studied history, economics, and politics at the city's university. Although he never completed his degree, Hess did come under the spell of the influential professor of geopolitics, Karl Haushofer. In post-war Germany, the politics of the Weimar Republic, as it was then called, was volatile. Hess blamed the socialist regime for Germany's economic woes, and he sought a radical change to German politics. Hess "became a member of the Freikorps Epp and participated in the liberation of Munich from communist revolutionaries in the spring of 1919" (Gellately, 62). Hess then joined the fascist National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP or Nazi Party for short), which was founded in 1920 as the German Workers' Party. Hess joined the party in the summer of 1920.

Hitler's Secretary

From 1921, Hitler was the leader of the ultra-nationalist Nazi party. Hess became Hitler's right-hand man and was directly involved in the Beer Hall Putsch (aka Munich Putsch) of November 1923. This amateurish attempt to take power by force was easily quashed by the authorities, and the leading Nazis, including Hess, were arrested, tried, and found guilty of treason. Hess received a prison term of 18 months. Hess and Hitler were imprisoned in Landsberg Prison, where they shared the same cell. Hitler used his time to write a book, Mein Kampf ('My Struggle'), which set out his thoughts on statecraft and how he would change Germany if he were its leader. Hess is credited with proofreading Hitler's text and adding the idea of Lebensraum to Hitler's vision of an all-powerful Third Reich. Lebensraum, meaning 'living space' for the German people, was not a new concept, but in post-war Germany, when times were tough with hyperinflation and high unemployment, the idea of new lands and new resources to boost the German economy appealed to many voters.

The Nazi Party was briefly banned but steadily recovered from the putsch debacle, gaining in popularity through the 1920s and early 1930s until Hitler was invited to become chancellor in 1932. From 1925 to 1932, Hess served as Hitler's private secretary, a position of significance since it allowed Hess to intercept all mail and filter exactly who met Hitler. Hess was directly involved in all Nazi policies, including racial ones such as the persecution of Jewish people, something which became institutionalised with the passing of the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. Hess also organised Hitler's speaking engagements and himself gave speeches in the Führer's place on many important occasions.

Despite his long personal history with both Hitler and the Nazi Party, by the early 1930s, Hess faced increasing competition within the higher echelons of the National Socialist movement. Hess was appointed the head of the Nazi Party's Central Political Committee in December 1932, where his brief was to increase the centralisation of the party. Hess was also made a general in the Nazi paramilitary group the SS (Schutzstaffel). Then, in April 1933, Hess was even made the deputy Führer. In December 1935, Hess was given the power to approve all Nazi official appointments. Then something changed between the Nazi leader and his most sycophantic of deputies. Hitler recognised Hess's absolute devotion to the cause, but he had also learnt that his deputy was not particularly suited, either physically or mentally, to the challenges that lay ahead as the Nazis strove to dominate Europe. Hess's unswerving loyalty had served Hitler's purpose as he rose to power, but as the 1930s entered their latter stages and war loomed on the horizon, Hess found himself increasingly on the fringes of real power. As the historian J. Dülffer notes, Hess "never achieved an importance commensurate with his title" (95).

Hess had been elected to the Reichstag (the German parliament) and was appointed a minister of state or Reichsminister, but Hitler effectively sidelined parliament completely by passing the Enabling Act of 1933. Hess did make something of a niche for himself in foreign affairs, notably orchestrating groups of Nazis in Austria to create problems for the government in preparation for the Anschluss (union) with Germany in 1938. A year later, Hitler appointed Hess his official successor after Hermann Göring (1893-1946). When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, Hess continued to focus on foreign policy, believing he could make contact with the British government through intermediaries and pull off a major diplomatic coup.

Personality

Hess was famously loyal to Hitler, but his withdrawn character won him few true friends in the Nazi movement. He also seemed intellectually adrift or, as the historian W. L. Shirer more bluntly put it, he was "a muddled man" (835) and "had never escaped from mental adolescence" (837). Hess's interests are described by Hitler's chief architect and armaments minister Albert Speer (1905-1981) in the following terms: "Hess occupied himself with problems of homeopathic medicine, loved chamber music, and had screwy but interesting acquaintances" (Speer, 83). Hess's many eccentricities ranged from a firm belief in astrology to the necessity of waving a divining rod under his bed each night before getting into it. Hess had a fragile state of health and ate specially prepared vegetarian meals for most of his life, a habit which put off Hitler and led to Hess not being invited to Nazi dinners with the Führer. Hess's mental health was also a continuing concern. Speer notes that Hess was "too sensitive, too receptive, [and] too unstable" (Speer, 252). Eccentric or downright odd, Hess's record of erratic behaviour still did not prepare Hitler or anyone else for one of the most bizarre events of WWII.

Flight to Scotland

Hess flew to Scotland on 10 May 1941 in an attempt to negotiate a complete turnaround in Britain and Germany's foreign policy. Hess wanted peace between Britain and Germany. He naively thought that the British government would simply forgive and forget what had so far passed in WWII, such events as the Dunkirk evacuation, the Battle of Britain, the London Blitz, and the North Africa Campaign. Hitler's plans to attack the USSR in Operation Barbarossa meant that Germany could well find itself fighting on two fronts if the Allied Western powers finally landed troops on the Continent. However, it is not clear that Hess was fully aware of the timing of Barbarossa, due to start one month after his flight to Scotland. Nevertheless, part of Hess's plan to make his peace proposals even more attractive to Britain was to emphasise that if Germany were permitted to concentrate on its battle against the USSR, then communism, the common enemy, would be defeated.

Finding himself estranged from the centre of Nazi power, Hess may have had a much more personal motivation which explains his literal flight of fancy: "…it is possible that he had a desperate desire to re-establish himself in Hitler's eyes" (Dear, 415). This view was endorsed by Speer, who wrote in his memoirs: "Hess was probably trying, after so many years of being kept in the background, to win prestige and some success" (Speer, 252). Hitler himself told Speer that his meetings with Hess were tiresome and that "he always comes to me with unpleasant matters and won't leave off" (ibid).

Hess flew from Augsburg in Bavaria to Scotland in a two-seater Messerschmitt 110; he landed via parachute. Hess had chosen his landing spot carefully as it was close to the home of the former Duke of Hamilton, now Lord Stewart, a man who had certain sympathies with Germany and who was, perhaps, in a position to arrange a meeting between Hess and King George VI (r. 1936-52). The Nazi parachutist landed safely and asked a farmer to take him to Lord Stewart. Hess would not reveal his identity until he had spoken to Lord Stewart personally. When finally meeting Lord Stewart, Hess revealed his identity and explained his purpose, stating he was "on a mission of humanity and that the Fuehrer did not want to defeat England and wished to stop the fighting" (Shirer, 835). Hess emphasised that, in any case, Germany was sure to win the war. Hess' attitude was very much that he, such a distinguished Nazi, was granting Britain a great favour by appearing out of nowhere to offer the olive branch of peace.

More official interviews followed, supervised by the diplomat Ivone Kirkpatrick, former First Secretary of the British Embassy in Berlin. Hess elaborated on his peace plan. He proposed that Britain allow Germany to do as it wished in Europe and, in return, Germany would allow Britain to do as it wished in the territories of its own empire. Hess also insisted that negotiations for such a peace treaty could only be conducted if the entire British government were changed and the prime minister, Winston Churchill (1874-1965), was not involved. This last demand was made since he considered the present government was entirely to blame for the war. Hess was now flying solo in the realms of absolute fantasy.

It is not clear what Hitler's involvement with the plan was prior to Hess's flight. The Nazi leader may have been aware of it since an adjutant of Hess's later claimed he had heard Hitler and Hess talking about the scheme. It may, however, have been discounted by Hitler as simply a wild idea that was only to be hypothetically considered. Certainly, when Hitler found out that Hess was on his way to Britain, he was furious. The Führer was seriously worried, too: "Who will believe me when I say that Hess did not fly there in my name, that the whole thing is not some sort of intrigue behind the backs of my allies?" (Speer, 251). Weather reports suggested that Hess would have difficulty reaching his destination, which led Hitler to wish hopefully: "If only he would drown in the North Sea! Then he would vanish without a trace, and we could work out some harmless explanation at our leisure" (ibid).

Hess had left a letter for Hitler in which he acknowledged the unlikely prospects for success and which stated that Hitler should distance himself completely from the scheme and claim that Hess was insane if all came to nothing. This is exactly what Hitler did, releasing an announcement to the German people via radio that Hess was mad and acting entirely on his own initiative. The statement was perhaps not far from the truth for even those officials who came into direct contact with Hess in Britain thought he displayed symptoms of being highly unstable. Hitler described Hess as a traitor and insisted he would be executed if he ever returned to Germany. Hess was rarely ever mentioned again in party circles.

Likewise, Churchill wanted nothing to do with Hess or his peace plan. Hess was never granted an audience with any member of the British government or the monarchy. The British public, although made aware of Hess's landing in Britain, was not informed of his negotiation objectives. The affair was at least a propaganda coup, which indicated the Nazis were not as unified as had appeared from the outside. Back in Germany, Hess's position was taken over by his deputy Martin Bormann (1900-1945), a gifted schemer who had already been usurping many of Hess's duties within the party. Hess's wife Ilse (née Pröhl), who had been deserted by her husband and who became a virtual outcast despite her own dedication to Nazism, was secretly given a small allowance by Hitler's mistress Eva Braun (1912-1945).

Hess, meanwhile, was treated as a prisoner of state in a military hospital in Buchanan Castle, Scotland. The renegade Nazi was subjected to psychiatric tests, and his mental instability was further indicated by two failed attempts at suicide. Ultimately, Hess was "diagnosed as a psychopath...[but] no one ever considered Hess clinically insane" (Dear, 415). He was moved to a succession of detention areas, first to the Tower of London, then to Mytchett Place near Aldershot in Hampshire, and then to Maindiff Court at Abergavenny in Wales.

Nuremberg Trials & Death

As Hess had once been the third most powerful Nazi, he was amongst those surviving senior Nazi figures brought to justice at the Nuremberg Trials, which began in November 1945 after the end of WWII. Göring was also tried at Nuremberg but requested not to be sat in the dock next to the constantly fidgeting Hess, who displayed such bizarre behaviour as repeatedly counting on his fingers and occasionally breaking out in laughter. Göring's request was refused. During the trial, Hess first claimed he was suffering from total amnesia and could not remember anything about his past, but he later changed his tune and admitted he was faking his forgetfulness.

Hess was found guilty of conspiracy and crimes against peace, but not guilty of war crimes or crimes against humanity. Unlike the majority of defendants, Hess escaped the death sentence, probably because of consideration of his mental fragility. Instead, Hess was given a term of life imprisonment.

Hess, like other top Nazis such as Speer, was sent to Spandau Prison in Berlin. It was in Spandau that Hess confided to Speer the reason for his remarkable flight to Britain in 1941 and his belief that he had been right to sue for peace. Speer wrote:

Hess assured me in all seriousness that the idea had been inspired in him in a dream of supernatural forces. He said he had not at all intended to oppose or embarrass Hitler. "We will guarantee England her empire; in return she will give us a free hand in Europe"…"He [Hitler] would have made it up with me. I'm certain of it. And don't you believe that in 1945, when everything was going to smash, he sometimes thought: 'Hess was right after all'?"

(Speer, 252-3)

While all other Nazis at Spandau were eventually freed, the USSR, perhaps because of the belief he had intended to involve Britain in an attack on Soviet territory during WWII, refused to sanction Hess's release. Hess remained the sole prisoner at Spandau from 1966 until his death on 17 August 1987. The official records noted that Hess had committed suicide by hanging himself using a length of electric wire. This final act of defiance was committed in a shed in the prison's garden. Given Hess's frailty – he was then 93 – rumours spread that he could not have hanged himself without help. There were even rumours that he had been murdered. Following Hess's death, Spandau Prison was demolished. Hess was buried in Wunsiedel in Bavaria, but when the grave became a focus of gatherings by pro-Nazi groups, Hess's remains were exhumed, cremated, and secretly scattered.