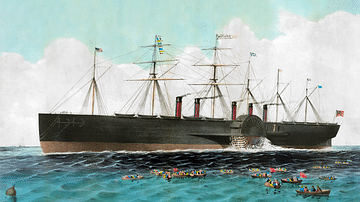

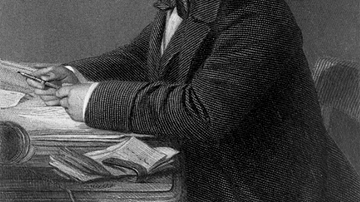

The SS Great Britain was a steam-powered ship designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) which sailed on its maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York in May 1845. It was the largest passenger ship in the world at the time and showed that giant metal steamships were faster and more energy-efficient than smaller wooden vessels.

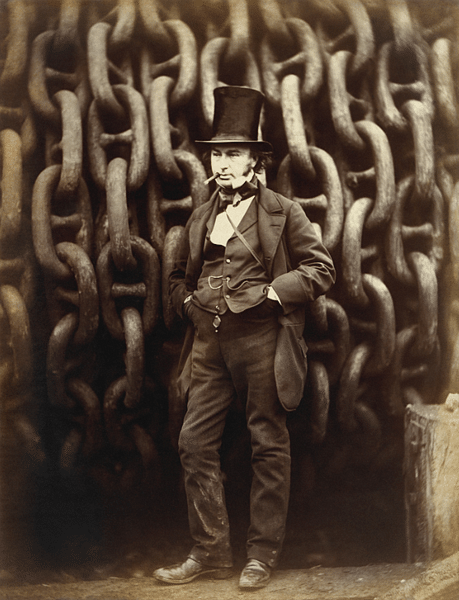

Brunel & Steamships

One of the problems of the early ships powered by steam engines was that they required a prodigious amount of coal and freshwater to run. With massive holds full of fuel, there was not a lot of space left for passengers, and so most of these early steamships were limited to rivers or close shore work. The British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel had the idea that massively increasing the scale of ships would solve the problem of space and a transatlantic passenger and freight service could be profitably run. The steamships would reach their destination port faster than sailing hips not because of their speed per hour necessarily but because they did not need to tack against a headwind and could take the straightest possible route.

Brunel was already a successful rail magnate, but in 1835, he formed the Great Western Steamship Company. Brunel's first giant steamship, the SS Great Western (SS denotes it as a steamship), was completed in 1838, but this vessel was made of wood. Great Western came second to SS Sirius, built by the Transatlantic Steamship Company, in the April 1838 'race' to become the first steamship to cross the Atlantic. Sirius technically won the race (if it had ever been such) by just one day, but it had started four days earlier than Great Western and had been obliged to start burning cargo when it ran out of fuel. Great Western, in contrast, had overcome the delay of a fire in the engine room on its first day out at sea, had not needed to stop for fuel in Cork, and had arrived in the United States after 17 days with over 200 tons of coal to spare.

Great Western could carry 128 passengers in luxurious style, plus a crew of 60. The return journey from New York to Bristol took just 14 days, double the speed that most sailing ships could manage (Sirius took 18 days for the same voyage back). It was obvious that Brunel had unlocked the key to faster ships. SS Great Western made 67 more crossings of the Atlantic and managed a top speed of 11 knots, although this was still just a little over half the speed of the fastest sailing ships, the tea clippers, in optimal conditions. Now Brunel had proven that steam could work, he was determined to build an even more modern transatlantic steamship, this time with an iron hull. The profits from Great Western would be ploughed right back into the production of an entirely new type of ship, bigger, faster, and more efficient than ever seen before.

Bigger is Better

Brunel was about to blow out of the water the widely-held view that a big iron ship would need so much fuel to push it through the water that it could never hope to cover long distances. Brunel, an instinctive mathematician, knew that he need not worry about the weight of the ship or its displacement in the water. The crucial consideration was how much water a ship had to push against as it moved forward. As long as the ship design was water-dynamic, the energy source (steam or sail) and material (wood or iron) were all but irrelevant (a metal hull is, in fact, around 70% lighter than a wooden one). Surface area was the key, not the volume of the ship. Indeed, the bigger the volume, the better in terms of the energy efficiency ratio compared to the overall weight. In mathematical terms, when considering the design of a ship and increasing the scale of the vessel, the volume increases as a cube while the surface area only increases as a square. In practical terms, a giant metal ship powered by giant heavy steam engines, thanks to its size, would have plenty of space for coal and passengers. It was this idea that Brunel showed to the world, and so he revolutionised shipbuilding thereafter.

Great Britain's Design

The initial design for SS Great Britain had the iron ship powered by two giant paddle wheels. These wheels needed massive metal drive shafts around 76 cm (30 in) in diameter, which led to Brunel asking James Nasmyth, his machine tools supplier, to come up with a solution on how to forge them. Consequently, Nasmyth invented the steam hammer in 1839, a steam-driven machine that pressed a huge weight to forge and bend metal for heavy industry.

The steam hammer was a great success but, as it happened, Brunel changed his mind and decided to look for a more innovative power source for his new ship than paddle wheels. Inspired by the SS Archimedes and its innovative use of a propellor, Brunel designed a propellor-driven engine for Great Britain. A propellor is under the water at the stern of the vessel and so, unlike paddle wheels, not affected by waves or the roll of the ship. A propellor also makes the ship easier to steer. Brunel designed a six-bladed propellor before changing it to a more efficient four-bladed one; remarkably, a modern propellor is only 5% more efficient than Brunel's design. Great Britain's giant propellor measured 4.7 metres (15 ft 6 in) across.

After problems with the construction of Great Britain's giant engines by Francis Humphreys (who was rather underfunded for the project), Brunel designed new ones himself. These were two steam-powered behemoths, the largest ever built at the time. The engines gave a combined power of 1,600 hp, which was transferred to the propellor shaft via four massive chains.

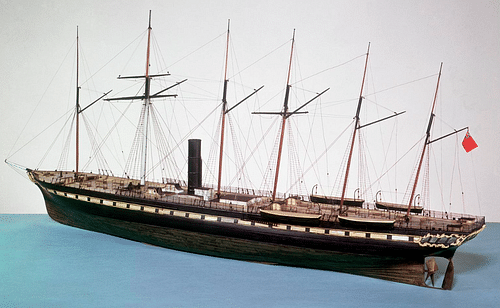

Great Britain was by no means the first metal ship, but it had an innovative double-skin hull, with the iron plates slightly overlapping for extra strength. It had a metal deck, two longitudinal bulkheads, and a series of watertight compartments running the length of what was, at that point in time, the longest ship ever built. Its length was 98 metres (321 ft), and its width was 15.5 metres (51 ft) at the widest point. The ship could still use wind power to save on fuel when required thanks to its six masts.

The hull of Great Britain was officially launched at Bristol on 19 July 1843, Albert, Prince Consort (l. 1819-1861) doing the honours with a bottle of champagne. Unfortunately, and rather embarrassingly for everyone involved, the ship was too big to get out of Bristol's floating docks. Parts of the lock system had to be dismantled so that the ship could reach the open sea and sail to London to be fitted out.

The ship then underwent sea trials before taking up its new home at Liverpool from where it would regularly cross the Atlantic to New York. SS Great Britain was the largest passenger ship in the world. The ship had a displacement of 3,675 tons, 50% more than Great Western. It had a crew of 130, and there was room for 252 passengers staying in first- or second-class cabins. The ship left Liverpool on its maiden voyage in July 1845 and took only 14 days and 21 hours to reach New York, over two days quicker than Great Western's maiden voyage. There were a few design alterations such as increasing the keel to make the ship more stable in high seas. The return voyage to England took 15 days. On a second crossing, this time in more favourable weather conditions, Great Britain made New York in 13 days and averaged a speed of 13 knots. The ship seemed to have a very bright future.

Running Aground & Later Uses

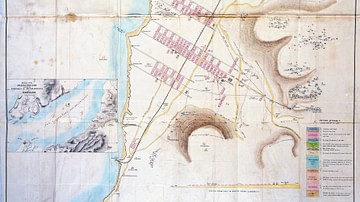

The fifth Atlantic crossing of the liner proved disastrous. In September 1846, Great Britain ran aground in Dundrum Bay on the northeast coast of Ireland after the captain used a faulty chart and perhaps suffered from a faulty compass. All passengers and crew were safely taken off the stricken giant. While engineers pondered how to get the great mass of iron off the beach, a wooden structure was built to protect the ship from the sea. This wall of timber was twice destroyed by storms, and Brunel was obliged to visit in person and design a wooden protective covering for the exposed rear of the ship. Eleven months later, Great Britain's damaged hull was finally repaired, the tons of accumulated sand were removed from inside, and the ship was refloated at the tremendous cost of £34,000 (over $3 million today).

Having never recouped the great costs to build the ship and with the delays caused by the design changes meaning they lost the lucrative government contract to ship post to the USA to the Cunard line, the Great Western Steamship Company decided to cut its losses and put Great Britain up for auction. There were no interested buyers at the reserve price of £40,000. In the end, the ship was sold to Gibbs, Bright & Company in December 1851 for around £18,000, one-seventh of the cost to build the ship.

Completely refitted, the ship took one more trip to New York and then was used as a passenger liner sailing regularly from Liverpool to Melbourne, Australia. During the Crimean War (1853-6), Great Britain saw service as a troop carrier but survived the experience to resume its successful passenger route to Australia. Still in service in 1870, the ship's glamorous past was but a memory, and it was used to transport coal from Wales to San Francisco. The grand old ship was converted to cheaper sail by Antony Gibbs & Son in 1882 and made its last fateful voyage in 1886 when it was wrecked off the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic. Remaining above the waterline, Great Britain had a long and ignominious end as a coal bunker and wool store for the next 50 years. Except that was not quite the end. In 1936, the ship had been scuttled, but it was resurrected in 1970, towed back to England on a giant barge, and restored as a tourist attraction in its original home of Bristol. Today the ship is managed by the SS Great Britain Trust.

Legacy

The SS Great Britain, although massively over budget in construction, had shown the way forward in ship design for the great passenger liners of the future. Brunel went on to build the massive SS Great Eastern, the new record holder for the largest ship in the world at 211 metres (692 ft) long, more than double that of Great Britain. It was completed in 1858 and could carry 4,000 passengers. Steamships could now cross the Atlantic faster than ever before, often in just ten days.

Soon, ambitious new routes to India, Australia, and the Americas were established with fewer refuelling stops or none at all. The world seemed to be shrinking. The quicker and cheaper access steamships gave to new resources and consumer markets worldwide certainly drove on the industry to produce ever more goods, which, in turn, led to the production of yet more steam-powered ships like the giants of the 20th century such as RMS Titanic.

As one historian noted, there was a cultural legacy, too, to these great ships ploughing the oceans:

Steamships also meant that – even after gaining its independence – the United States kept in touch with the mother country. it is arguable that it is because of steam that we can talk about 'Western culture' at all. (Dugan, 97)