The SS Great Eastern was a steam-powered ship designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) which sailed on its maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York in June 1860. At the time, it was by far the largest passenger ship ever built, a record it would hold for 49 years. Great Eastern laid the first cross-Atlantic telegraph cable in 1866.

Brunel & Steamships

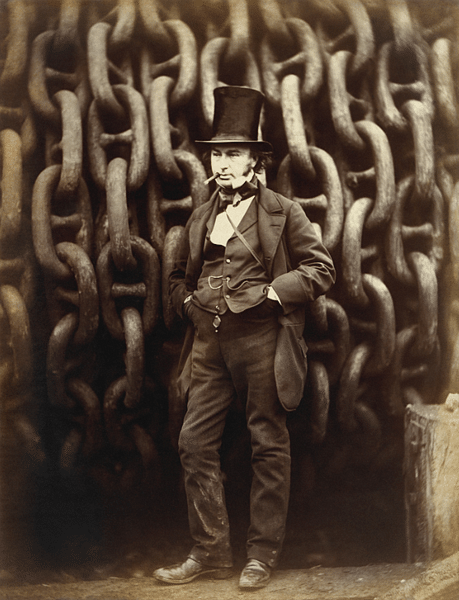

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was a British engineer known primarily as a successful rail magnate, but in 1835, he formed the Great Western Steamship Company. Brunel's first giant steamship, the SS Great Western (SS denotes it as a steamship), was completed in 1838. Made of wood and powered by giant paddle wheels, Great Western showed that large steam-powered ships could carry sufficient fuel, passengers, and cargo to make long voyages profitable. Great Western came second to SS Sirius, built by the Transatlantic Steamship Company, in the April 1838 'race' to become the first steamship to cross the Atlantic from Britain to New York. However, Brunel's ship had set off several days later than Sirius and was much more efficient in terms of fuel consumption. Brunel had proven that steam power could work for ships just as it did for trains, and he was now determined to build an even more modern transatlantic steamship, this time with an iron hull. The profits from Great Western were ploughed right back into building the SS Great Britain.

The largest passenger ship in the world at the time at 98 metres (321 ft) in length, Great Britain sailed on its maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York in May 1845. Great Britain was driven by an innovative propellor system rather than the traditional paddle wheels, although it also had six masts for sails when conditions were favourable. The ship made several crossings of the Atlantic, averaging 13-15 days per voyage. Unfortunately, the huge ship ran aground in Ireland in September 1846, but Brunel was by now ambitious for an even bigger and grander ship. Brunel's third great steamship was the SS Great Eastern.

The Great Dream

The idea of building a third iron steamship was to provide a passenger service between Europe, the Far East, and Australia. The Australian Mail Company was particularly interested in a faster means to deliver mail between Britain and Australia. Brunel had the idea that if a ship were big enough, it could carry enough fuel to sail around the world. Such a ship would not need, as was the norm, to stop at regular coaling stations like Cape Town and so could make long voyages much quicker than any rival. The problem with this idea was that the Australian Mail Company was not convinced of Brunel's scheme and ordered two smaller ships to meet its needs. Brunel forged ahead anyway, forming the Great Eastern Steam Navigation Company in 1853. At this period of construction, the ship was known as the Leviathan, to Brunel, it was his 'great babe'. It was to be a giant ship that no business had commissioned. Brunel hoped that when his 'great babe' became a reality, the customers would come knocking on his door. It was a risk as big as the ship he hoped to build. Brunel "had never before been so deeply committed to a project, financially and morally as well as intellectually and practically" (Brindle, 134).

With no dock big enough to accommodate this monster of the sea, it was built on purpose-built wooden beams driven into the shoreline. This wooden cradle consisted of 12,000 tons of timber. When or if it was ever completed, the ship would have to be launched sideways into the River Thames using massive chains operated by even bigger steam engines.

Brunel's project had been dealt a second blow when he failed to gain the lucrative British government contract to ship mail to India, China, and Australia. Investors began to feel nervous that Brunel would never finish his great ship when the constructor, John Scott Russell of Millwall went bankrupt in February 1856. Still only half-finished and with costs ballooning, Brunel had to fight off creditors who wanted to sell Great Eastern as it was. The hull was finished by the end of 1857, but the official launch was a disaster; Brunel's carefully designed braking winches, which carried chains with links each weighing 27.2 kilograms (60 lbs), span out of control, and one man was killed. Brunel had decided to add iron railings to the wooden cradle supporting the ship, and these had created too much friction with the ship's iron hull. It took an agonising two months to work out a way to safely lower the hull into the river. On 1 February 1858, the Great Eastern was finally afloat and ready for fitting out. The original budget for launching the hull had been set at £14,000, but it had, in fact, cost £120,000. The ship seemed to be a money pit with an insatiable appetite.

By the autumn of 1858, the ship was nearing completion, but another financial catastrophe occurred when the Great Eastern Steam Navigation Company went bust. With costs spiralling, Great Eastern, critics began to say, was Brunel's great folly, and, not for the first time, the engineer was accused of trying to build a dream instead of a physical reality. A new set of investors was ultimately formed and a new company was created, the Great Ship Company, which essentially bought out the defunct GESNC and so took over the ship. Construction of Great Eastern was resumed, and its paddle wheel and propellor systems were tested through July and August of 1859.

The ship was finally ready for its first sea trials with a trip to Weymouth and then Anglesey in Wales, in early September. The ship set off without problems, but on 8 September, an explosion, caused by someone carelessly leaving a stopcock closed on a heater, killed five men and blew the forward funnel off the deck. Repairs were made to the ship, but its reputation as an unlucky vessel proved more difficult to remedy. Nevertheless, with its great structural strength and emphasis on luxury fittings, the liner was a forerunner of the great transatlantic ships yet to come.

Record-breaking Statistics

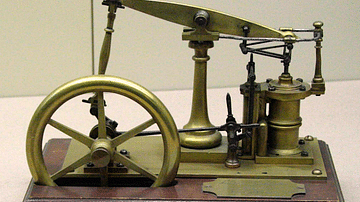

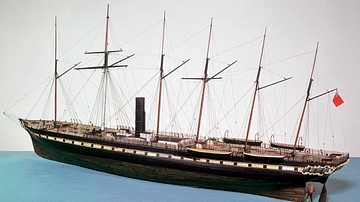

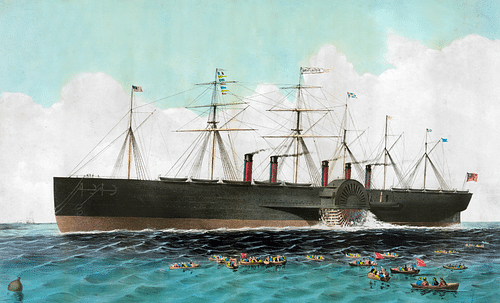

Everything about Great Eastern was record-breaking. The ship combined two paddle wheels at the sides with a propeller at the stern. The propellor gave some 60% of the overall power. The paddle wheels were 17 metres (56 ft) across and provided around 40% of the necessary power to drive the ship. One giant steam engine powered the propellor while a second drove the paddle wheels; each engine weighed 90 tons. The engines were the biggest ever built at the time and were supplied by James Watt & Co. They had massive cylinders which measured 1.88 metres (6 ft 2 in) in length. The engines gave a total of 3,150 horsepower, which was double the power of any existing ship. Combining all three sources of power, the ship also had six masts for sails when conditions were favourable. The top speed of Great Eastern was around 14 knots.

The Great Eastern was by far the largest ship in the world, more than double the size of SS Great Britain. It was 211 metres (692 ft) long and 25.3 metres (83 ft) at its widest point; just its propellor was more than 8 metres (26 ft) across. In total, over 3 million rivets were used to secure the ship's 30,000 iron plates, each plate measuring 3 x 0.8 metres (10 ft x 2 ft 9in). The ship's tonnage in sheer weight was 18,915 tons. It displaced 27,000 tons. It could carry 4,000 passengers and 418 members of crew. In addition, the ship could transport around 3,000 tons of cargo.

Great Eastern was so large that Brunel designed it with girders sandwiched between a double hull, a strengthened keel, and several watertight bulkhead compartments. There were also two longitudinal bulkheads to add even more strength and to separate the engine from the boilers as a safety measure. These features made sure Great Eastern could survive a deliberate grounding, necessary since no dry dock in the world was yet big enough to accommodate the ship when it inevitably needed repairs.

A Transatlantic Liner

Great Eastern made its maiden voyage across the Atlantic in June 1860, sailing from Liverpool to New York. Unfortunately, Brunel did not live to see the achievement of his dream, he died of a stroke the year before. Brunel's health had long been in decline, perhaps related to the stress of the Great Eastern project but more likely due to a diagnosed kidney complaint, Bright's disease.

Great Eastern was never used, as Brunel had intended, to carry passengers and freight to Asia. The ship was, instead, employed as a transatlantic liner but was a victim of its own size as smaller vessels outpaced it. The ship managed to scrape a small profit for its owners until disaster struck in September 1861 when it was hit by a storm and needed extensive repairs. In August 1862, the ill luck that Brunel's ships seemed to suffer hit again when Great Eastern ran aground off the U.S. coast. Unable to meet the heavy costs of these misadventures, the Great Ship Company was obliged to put Great Eastern up for auction in 1864. There were no takers, and the ship was later sold at a cut price of £20,000 to begin a new, less glamorous role.

Later Service

From 1865 until 1873, Great Eastern was used to lay undersea cables, including the first cross-Atlantic telegraph cable (in 1866, at the second attempt), which stretched from Ireland to Newfoundland. The ship was ideally suited to this type of work since it was very stable, could easily carry the massive rolls of cable, and was highly manoeuvrable. Great Eastern went on to lay cables from England to France and from England to India.

The ship made a brief return to passenger service when it travelled from Liverpool to New York in 1867. A famous passenger was the celebrated French novelist Jules Verne (1828-1905) who, so impressed was he with the experience, set his 1871 novel Une ville flottante ("A Floating City") on the ship.

SS Great Eastern was retired from laying cables and spent 12 years in dock at Milford Haven. The ship was bought by Edward de Mattos in 1885; he paid £25,000 for it and leased it for use as a floating but immobile palace of entertainment on the River Mersey. People paid a shilling to be ferried to the ship and enjoy its concert hall and stalls, much like the piers that could be visited in seaside resorts. The ex-liner was eventually broken up and sold for scrap in 1888, but it was such a huge mass of iron it took 200 men an expensive two years to do the job. It seemed the Great Eastern, once again a victim of its prodigious size, could never really make a profit for anyone.

Brunel had been a visionary, and Great Eastern was a giant leap forward in maritime design and function, but the vessel perhaps stretched the technological limits of the day too much. "Too big, too far ahead of her time…she was an engineering dream, a triumph of design over function, of ambition over common sense" (Brindle, 140-1). But despite all the problems, disappointments, and tragedies, Great Eastern had shown the way forward for the even bigger liners of the 20th century like the Cunard Line's RMS Lusitania (1906), the new record holder for sheer size, and then the even bigger and grander RMS Titanic (1912).