The Sacsayhuaman (also Saksaywaman or Saqsawaman, meaning 'Royal Eagle') fortress-temple complex lies at the northern edge of the former Inca capital Cuzco. Constructed during the reign of Pachacuti (1438-1471 CE) and his successors, its massive, well-built walls remain today as a testimony not only to Inca power but also the skills of Inca architects and their approach of blending their monumental structures harmoniously into the natural landscape. The Sacsayhuaman is still used today for reenactments of Inca-inspired ceremonies.

Construction

The fortress was the largest structure built by the Incas. It was constructed on an elevated rocky promontory facing the northern marshy ground outside the Inca capital of Cuzco. Pottery finds indicate that the site had previously been occupied by Inca residents. Begun in the reign of the great Inca empire builder Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, or perhaps his son Thupa Inca Yupanqui in the mid-15th century CE, the design was credited to four architects: Huallpa Rimachi, Maricanchi, Acahuana, and Calla Cunchui. The first structures were made using only mud and clay. Subsequent rulers then replaced these with magnificent stonework which employed huge finely-cut polygonal blocks, many over 4 metres in height and weighing over 100 tons. To complete such a massive project 20,000 labourers were drafted in under the well-established Inca system of extracting both goods and labour from peoples they conquered. Working in a system of rotation 6,000 were given quarrying duties while the other 4,000 dug trenches and laid the foundations. The walls of the fortress were built in vertical sections, probably, each section being the responsibility of one ethnic labour group.

The Incas were master stonemasons. Huge blocks were quarried and shaped using nothing more than harder stones and bronze tools. Marks on the stone blocks indicate that they were mostly pounded into shape rather than cut. Blocks were moved using ropes, logs, poles, levers, and earthen ramps (telltale marks can still be seen on some blocks), and some stones still have nodes protruding from them or indentations which were used to help workers grip the stone. That rocks were roughly hewn in the quarries and then worked on again at their final destination is clearly indicated by unfinished examples left at quarries and on various routes to building sites. The fine cutting and setting of the blocks on site was so precise that mortar was not necessary. Finally, a finished surface was provided using grinding stones and sand.

Experimental archaeology has demonstrated that it was much quicker than scholars had previously thought to prepare and dress the stones used by the Incas. Even so, it would have taken many months to produce a single wall. The Incas also ensured that their blocks interlocked and the walls were sloped to maximise their resistance to earthquake damage. Time has proved their efficiency as 500 years of earthquakes have done remarkably little damage to Inca structures left in their complete state and the Sacsayhuaman is no exception.

Design

If the theory that all of Cuzco was laid out to form a puma shape when seen from above is correct, then Sacsayhuaman was its head. The fortress has three distinct terraces which recede backwards on each other. The walls, each reaching a height of 18 metres, are laid out in a zigzag fashion stretching over 540 metres so that each wall has up to 40 segments, which allowed the defenders to catch attackers in a crossfire; a result helped also by the general curvature of the entire fortress facade. In addition, Inca architects very often sought to harmoniously blend their structures into the surrounding natural landscape and the outline of the Sacsayhuaman was similarly built to mimic the contours of the mountain range which towers behind it. This is particularly evident when the sun creates deep triangular shadows between the zigzag terraces in exactly the same way that it does on the mountain range with its peaks and valleys.

In another defensive consideration, there is only one small doorway on each terrace which gave access to the interior buildings and towers on the hillside behind. Eyewitness Spanish accounts describe a large circular four or five-storey tower centrally placed within the fortress and its foundations (along with those for two others) can be seen today. To the rear of the complex, in an area known as the Suchuna (slide), there were more terraces, patios, outbuildings, and a system of water supply including cisterns and aqueducts. Finally, there is an area of stepped terracing cut into the side of the Rodadero Hill, which is thought to have been a religious shrine, perhaps dedicated to the earth goddess Pachamama, or a viewing platform for the Inca ruler to watch ceremonies from or a place for astronomical observations.

Function

On completion, the fortress was said to have had a capacity for at least 1,000 warriors, but it was rarely needed as the Incas did not suffer invasions from enemy states. Probably, for this reason, Sacsayhuaman was designed as much more than a fortress. The complex included temples, notably one to the sun god Inti, and was used as a location for Inca ceremonies. The Sacsayhuaman was also a major Inca storage depot where arms, armour, foodstuffs, valuable textiles, ceramics, metal tools, and precious metals were kept.

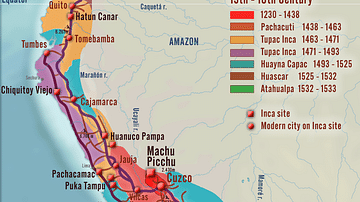

The Sacsayhuaman did operate as a fortress during the Spanish conquest of Peru from 1532 CE. The Spaniards, led by Francisco Pizarro, conquered Cuzco shortly after killing the Inca ruler Atahualpa in 1533 CE but then faced an organised and sustained siege from a large Inca army. Pizarro sent his brother Juan to attack the Sacsayhuaman using cavalry and then climb the walls with ladders. The offensive was successful, even if Juan died in the process, and the occupation of the fortress allowed the Spanish to resist the siege.

Later Use

Following the collapse of the empire after the European invasion, most of the stones of the Sacsayhuaman were reused elsewhere in the colonial buildings of Cuzco. The ruins were covered in earth by the Spanish to prevent their use by rebel Inca forces and the site was not rediscovered until its excavation in 1934 CE. Today the ruins of the fortress are the location for the annual Inca reenactment festival the Inti Raymi, held on the winter solstice.