Saint Gregory the Illuminator or Enlightener (previously known as Grigor Lusavorich, c. 239 - c. 330 CE) was the first bishop of the Armenian church, and he is widely credited with converting king Tiridates the Great to Christianity, formally establishing the Armenian Church, and spreading that religion throughout his country. Saint Gregory is the patron saint of Armenia.

Early Life

The life of Saint Gregory was first recounted in a biography dating to c. 460 CE and the more or less contemporary History of the Armenians by Agathangelos. The saint's original name was Grigor Lusavorich, and he was born in Cappadocia between 239 to 257 CE (dates disputed due to conflicting sources). He was the son of Anak Partev the Parthian, who, being in the pay of the rival Sasanian Empire in Persia (224-651 CE), infamously murdered the Armenian king Khosrov of Kadj. The Lusavorich family was both wealthy and influential but they were all wiped out by the revenging relatives of Khosrov. Fortunately for Gregory, he, the sole survivor of the purge, was whisked away by his nanny to the safety of Cappadoccia.

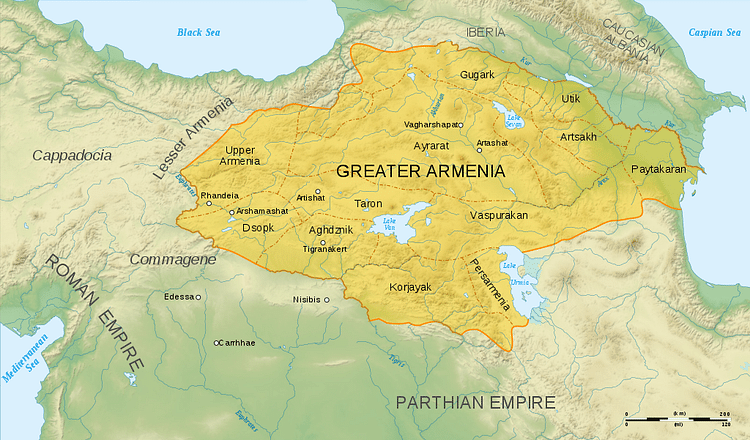

Gregory was raised as a Christian and attended a Greek Christian school. On returning to Armenia, Gregory gained a position as a palace functionary at the court of the Armenian king at Vagharshapat. There he made a stance against the pagan religion of the period and refused to participate in its rites. The reigning monarch was Tiridates IV (Trdat III or IV), or Tiridates the Great as he would become known (r. c. 298 to c. 330 CE), and he had the troublesome Gregory imprisoned, tortured, and thrown into the terrible Khor Virap prison at Artashat. Known as the “pit of oblivion”, nobody ever returned from Khor Virap.

Conversion of Tiridates the Great

After a 13-year ordeal down in the pit, Gregory was given a miraculous lifeline by, of all people, Tiridates' sister Khosrovidukht. She had had a vision that the only person who could save the king from his terrible illness (lycanthropy), the symptoms of which were to behave like a wild boar, was Gregory. This was especially ironic as the illness had only come on following the king's orders to murder a group of Christian nuns who had fled persecution in Rome. Accordingly, Gregory was freed from Khor Virap and, naturally, besides trying to cure the king, he made his best efforts to convert him to Christianity.

Tradition (and the Armenian Apostolic Church) records that Tiridates was cured and converted to his new faith in 301 CE by Saint Gregory. However, modern historians prefer the more secure date of around 314 CE following Roman emperor Constantine I's Edict of Milan in 313 CE which legalised Christianity in the Roman Empire. It seems probable that Christianity actually entered Armenia by two separate but more or less contemporary routes, thus explaining the conflicting accounts in ancient historical records. Saint Gregory represented the transmission via Greek culture in the capital while in the provinces a greater influence came from Syria, especially via the Armenian communities in the cities of Mtsbin and Edessa in Mesopotamia. Thus, the spread of the religion was much slower, more organic and haphazard than ancient sources present.

However precisely it happened, and which part is legend and which part fact, Armenia did become a Christian state, and it was a momentous moment in the country's history as the historian R. G. Hovannisian here explains:

The conversion of Armenia to Christianity was probably the most crucial step in its history. It turned Armenia sharply away from its Iranian past and stamped it for centuries with an intrinsic character as clear to the native population as to those outside its borders, who identified Armenia almost at once as the first state to adopt Christianity. (81)

The Spread of Christianity

Gregory was made the first bishop (katholikos) in Armenia's history in Caesarea in Cappadocia, again c. 314 CE, and he set about formally establishing the Christian Church as soon as he returned to the kingdom of Armenia. To get the ball rolling Tiridates gave Saint Gregory up to 15 provinces worth of territory to establish the Armenian Church. The old pagan temples were torn down, Zoroastrian sites were converted to Christian ones, and the whole nation was obliged to embrace the new faith. Churches and monasteries sprang up everywhere, including at the Khor Virap, Gregory's home for so long, which was eventually converted into a monastery. The Armenian aristocracy quickly followed the royal family's example and many noble families converted to Christianity.

Armenia had long been fought over by Rome and Persia as it stood between those two great empires of the period. Although the adoption of Christianity shifted Armenia closer to Roman religious culture, one consequence of the move was that the persecution of the religion by Persia helped to create a more fiercely independent state. The Sassanid Empire had been trying to impose Zoroastrianism on its neighbours and Christianity was a means to resist Persian political and cultural imperialism. Rome, on the other hand, saw the value in permitting the spread of Christianity as a means to maintain Armenia's independence from Persia.

Tiridates the Great may also have adopted Christianity for internal political reasons - the end of the pagan religion (with its heady mix of Greek, Persian, Semitic, and local gods) was a fine excuse to confiscate the old temple treasuries which were jealously guarded by a hereditary class of priests. Further, a monotheistic religion with the monarch as God's representative on earth might well instil greater loyalties from his nobles and people in general. As it turned out, the Armenian Church became an independent institution with noble families providing its key figures and monasteries able to achieve self-sufficiency through their own landed estates.

Education & Warfare

Saint Gregory used two principal methods to spread Christianity in Armenia: education and military power. Schools were established in which children of the existing pagan priestly class were prepared for the Christian priesthood. Meanwhile, military units were dispatched to destroy pagan temple sites and confiscate their vast riches, which were then used to fund Christian building projects. Naturally, many temple sites, along with several rich and semi-independent feudal principalities, resisted the new policy and these were put to the sword. Gregory oversaw mass baptisms in the Euphrates River; bishops were then appointed from the noble clans (nakharars) and lower priests from the class of knights (azats) to guide the ever-growing flock of faithful.

Gregory established his new headquarters at Ashtishat. The most important ancient temple site in Armenia, Ashtishat was a symbol of the new order and chosen by Gregory as a result of a vision in which he realised that Jesus Christ had descended to earth at that very spot. There a monastery was built, the Surb Karapet with its shrine to Saint John the Baptist. The monastery would remain an important site of Christian pilgrimage for 16 centuries until its destruction in 1915 CE.

Retirement & Successors

Later in life Gregory retired to the seclusion of the cave of Mane in northwestern Armenia where he lived as an ascetic. Gregory died there of old age sometime between 325 and 330 CE. The former bishop's remains were buried at Tordan on the Euphrates River in the western province of Daranaghik, although later his bones would become prized relics in various churches across the country.

The descendants of Gregory carried on his work, notably his younger son Aristakes, who, known for his asceticism, was the next bishop (the office was hereditary) and who attended the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325 CE. When Aristakes died in 333 CE, Gregory's other son Vrtanes became bishop, a role which passed to his son Husik I c. 341 CE. There would be several more descendants after that, many of whom were made saints, as their founding father Gregory had been. Saint Gregory had many monuments built in his honour but perhaps the most celebrated was the cathedral at Ani built by the great architect Trdat for King Gagik (r. 1001-1010 CE).

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.