The Salado culture is a term used by historians and archaeologists to describe a pre-Columbian Southwestern culture that flourished from c. 1200-1450 CE in the Tonto Basin of what is now the southern parts of the present-day US states of Arizona and New Mexico. Although scholarly debate continues as to the exact origins of the Salado culture, as well as how it disappeared, there is some consensus among scholars and archaeologists that the Salado culture had distinctive art, architectural traditions, and burial practices that distinguish them from their Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi), Mogollon, and Hohokam neighbors. Among the ancient cultures of the US Southwest, the Salado culture is especially noted for its stunning iconographic designs and pottery production. The US archaeologist Harold Gladwin (1883-1983 CE) was the first to analyze these cultural traits and a shared artistic style in the 1920s CE, and he referred to this indigenous culture as the "Salado." The name stems from the Salt River (Spanish: Río Salado), which flows through the valley of their cultural genesis.

Prehistory & Geography

The area in and around the Tonto Basin forms part of a large intermountain basin, which facilitated human settlement as it was rich in natural resources. The Salt River runs through eastern Arizona, slicing through the White Mountains until it intersects with the Gila River in what is now central Arizona. The land therein is surprisingly fertile, and a diverse array of flora grows in a series of interlinked microenvironments: walnut trees, sycamore, mesquite saguaro cacti, and jojoba are all found in this region. There are even pinyon and juniper bushes at higher elevations, in addition to other flowering plants that produce nuts and fruit. Wild game is thus also plentiful: deer, rabbits, and quail frequent the area.

The lands that the Salado culture came to occupy witnessed human inhabitation long before the emergence of the Salado. (Their spectacular emergence is commonly referred to as the "Salado Phenomenon" by academics.) The work of archaeologists in recent years has shown that humans have inhabited the Tonto Basin since c. 5000 BCE. Several Paleo-Indian mammoth kill sites are located in what was once considered the Salado heartland, and there are signs that indigenous peoples constructed small cliff dwellings as early as c. 3500 BCE. Permanent occupation, however, dates from c. 100-600 CE, when the peoples belonging to the Mogollon settled the eastern parts of this region and left pottery shards as evidence of their presence. The Hohokam moved into the Tonto Basin from around what is now the vicinity of the modern city of Phoenix, Arizona between c. 600-750 CE. The Hohokam constructed their ubiquitous pit-houses, built complex irrigation canals, and cultivated maize, squash, beans, and cotton. Despite the presence of pottery remains that attests to the fact that the Hohokam occupied the Tonto Basin for at least 300 years, archaeologists and historians are divided on whether or not the Hohokam people eventually left the region to return to the Phoenix Basin sometime around 1150 CE.

Many archaeological remains and artifacts belonging to the Mogollon and Hohokam were destroyed due to the construction of the Theodore Roosevelt Lake reservoir and a masonry dam in 1911 CE. (Unfortunately, the construction of this same lake destroyed innumerable archaeological remnants from the Salado culture as well.) It is generally believed that a high level of cross-cultural exchange occurred in the region between the Mogollon and Hohokam people before the arrival of any newcomers.

Formation of the Salado Culture

The 12th and 13th centuries CE were pivotal in the formation and subsequent cultural development of the indigenous peoples of the ancient Southwest. Environmental data shows that years of drought were followed by years of torrential rains and flooding across the region of what is present-day Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. Deprivation caused by environmental stresses combined with social chaos and political disorder likely prompted the migration of many peoples, but especially the Ancestral Puebloans, to seek fertile lands near the Little Colorado River (in Arizona), the Rio Grande (in New Mexico), and the Tonto Basin (in Arizona).

Between c. 1200-1300 CE, Ancestral Puebloan peoples (and probably some Mogollon peoples as well) entered the Tonto Basin, encountering other Mogollon and Hohokam communities. Here, the three cultures intermixed socially and intermarried, adopting or adapting new cultural practices in turn based on utility and necessity. Archaeologists have debated the genesis of the Salado culture since the 1920s CE. Some explained and theorized the emergence of the Salado culture as a mixture of Mogollon and Hohokam populations, Hohokam and Ancestral Puebloan populations, or even as a subset of the Hohokam cultural tradition. In the last couple of decades, archaeologists have come to view the rise of the Salado culture in ways similar to the perspective first proposed by Harold Gladwin. It is probable that the Salado culture is truly the end result of an amalgamation of the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Ancestral Puebloan cultures and their respective populations - a veritable cultural melting pot in the ancient Southwest. The development of the Salado culture can be best understood then as the result of migration and localized cultural evolution in situ.

Salado Culture & History

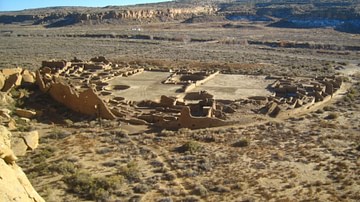

Members of the Salado culture constructed small villages or hamlets as well as shallow pit structures. They also built small, ceremonial platform mounds, irrigation canals, multi-storied pueblo made of adobe, and cliff dwellings by c. 1300 CE. One does find T-shaped doorways like those found in Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Wupatki, and Casas Grandes, which suggests strong Ancestral Puebloan and Mogollon influence in Salado architecture. Curiously though, one does not find kivas at sites associated with the Salado culture, and Salado structures were often surrounded by stone walls, which features prominently in Hohokam architectural traditions. (It is worth noting too that many Salado constructions sit on top of former Hohokam residences in the Tonto Basin.) Storage spaces were set aside for agricultural and artisan goods, and space was generally allocated by purpose.

The largest Salado towns once contained as many as 1500 people, and other settlements included impressive compounds that contained 30-100 rooms. At Tonto National Monument in Arizona, one can still see the Upper and Lower Cliff Dwelling, which encompassed over 50 rooms in two-story complexes. Originally occupied from c. 1225-1400 CE and located near what is present-day Globe, Arizona, Besh-Ba-Gowah contained a 200-room multi-storied pueblo. Besh-Ba-Gowah was one of the largest Salado settlements that archaeologists have found. The Tonto Basin may have supported up to 10,000 people during its occupation by the Salado culture although a more precise figure is difficult to estimate.

Those who belonged to the Salado cultural group grew corn, cotton, squash, and amaranth, as well as beans. They also cultivated agave and used yucca to weave sandals, mats, and baskets. The Salado cultural group traded extensively with their neighbors in the Southwest, and their pottery — commonly referred to as "Roosevelt Red Ware," "Salado Red Ware," or "Salado Polychrome" — has been found as far away as Casas Grandes, in what is now Chihuahua, Mexico, where it was highly prized. Salado pottery demonstrates a striking combination of white, black, and red colors in geometrical shapes and lines with additional compositional characteristics. Many archaeologists conclude that among the ceramic traditions of the ancient Southwest, the Salado tradition produced the most widely traded pottery.

The Salado cultural group initially buried and cremated their dead. (The Ancestral Puebloans and Mogollon buried their dead, while the Hohokam cremated theirs.) Archaeologists have unearthed the remains of many individuals who were buried in supine positions. Salado dead were laid to rest in plazas or patios; at Besh-Ba-Gowah, archaeologists have uncovered 150 skeletons from its central square. Some graves are filled with what appears to be ritual offerings, including vessels, precious stones or minerals, and even furniture. This has led some archaeologists to theorize that the placement of the dead reflected the indigenous social hierarchy of a Salado community. Little is known about religious customs or practices among the Salado cultural group, as it is difficult for researchers to differentiate religious objects from other artifacts.

Collapse of the Salado Culture

The disappearance of the Salado culture remains yet another mystery among many in the ancient Southwest. It is known that after c. 1350 CE, climatic changes adversely affected Salado settlements in Arizona and New Mexico. The area in and around the Tonto Basin became drier in the 14th century CE, but there were periods of devastating floods and famine too. It is credible that some inhabitants began to relocate to larger Salado settlements or elsewhere beginning in the late 14th century CE, and this pattern of outwards migration continued or even accelerated in the 15th century CE. Some archaeologists have speculated that many communities collapsed when irrigation fields were destroyed by floods and salinization, which hampered agricultural production at Salado farms. This is exactly what happened at Pillar Mound in Arizona, which was deserted after a torrential flood destroyed its irrigation canals. There is some evidence of intercommunal strife at Besh-Ba-Gowah, and violence may have encouraged migration en masse as well. Native American oral traditions tell us that some members of the Salado cultural group migrated north and northeast to join the Hopi and Zuni communities, some joined the pueblos along the Rio Grande in what is modern New Mexico, and others moved south towards Casas Grandes.