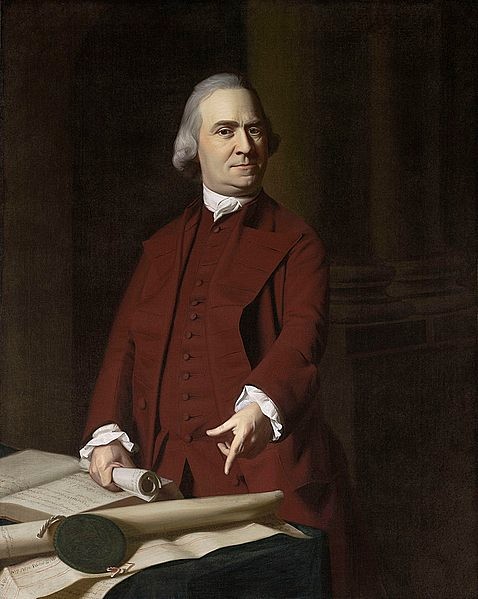

Samuel Adams (1722-1803) was a prominent Patriot leader in the American Revolution (1765-1789), and a Founding Father of the United States. He was one of the most vocal opponents of 'taxation without representation', was a founding member of the Sons of Liberty, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and the fourth Governor of Massachusetts (served 1793-1797).

Adams was a lifelong resident of Boston, Massachusetts, who, prior to the Revolution, had failed at every career he tried. It was not until the Stamp Act crisis of 1765 that he found his political voice, writing anti-British essays in colonial newspapers; the "simplicity, purity, and harmony" of his prose quickly elevated him to one of the most influential Patriot leaders in the New England colonies (Schiff, 72). He worked tirelessly in the defense of colonial rights, keeping the revolutionary flame alive even when others would not. A radical and early supporter of independence, he helped unify the Thirteen Colonies by setting up a system of committees of correspondence in 1772, played a leading role in the leadup to the Boston Tea Party, and helped draft the Articles of Confederation and Massachusetts Constitution.

His propensity to resort to propaganda, as well as his association with the Sons of Liberty, has turned him into a controversial figure, with his critics accusing him of instigating mob violence to achieve his ends; he was a "Machiavelli of chaos", according to his rival Thomas Hutchinson (Schiff, 7). Other contemporaries praised his zeal and political shrewdness, with Thomas Jefferson calling him "truly the Man of the Revolution" (Boatner, 8). Whichever was the case, Adams was certainly steadfast in his principles, stemming from his Calvinist upbringing, which led him to eschew financial gain in favor of maintaining virtue. His shadow loomed large over the revolutionary era, and he played a major role in prodding his fellow Americans onto the path toward nationhood.

Early Life

Samuel Adams was born on 27 September 1722 in Boston, the largest city in the British colony of Massachusetts Bay. He was one of twelve children born to Samuel Adams Sr. and Mary Fifield Adams, of whom only three would live past infancy. The elder Samuel Adams wore many hats; he was a deacon at the Old South Congregational Church, he was a local politician who served in an informal, populist organization called the Boston Caucus, and he operated a malthouse that had been in the Adams family for generations, providing Boston with much of the malt it used to brew its beer. The Adamses were by no means rich, but owned a sizable chunk of property and a modest home on Boston's modern-day Purchase Street.

The younger Samuel Adams attended Boston Latin School before enrolling in Harvard College in 1736 at the age of 13. He graduated four years later after an unremarkable academic career; the most noteworthy thing about his undergraduate education was that he was once fined by the school for "drinking prohibited Liquors" (Middlekauff, 165). After graduation, he tried his hand at several careers but failed at every one. He was first apprenticed to a merchant but was sent home after showing little aptitude for the trade. He next borrowed £1,000 from his father to start his own business but gave up after he lost the money. He even toyed with the idea of becoming a minister but quickly gave up on that as well. As he bounced between prospects, he found steady work at the malthouse, eventually becoming a partner in the family business.

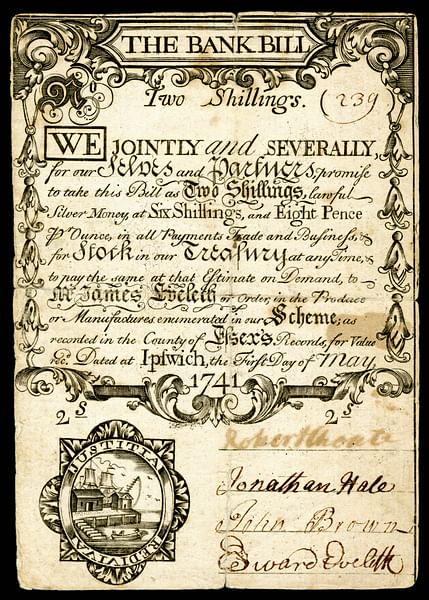

Land Bank

As the son struggled to make his way in the world, the father was attempting to alleviate the financial hardships of the community. By 1739, there was a lack of hard currency circulating in Massachusetts, prompting Deacon Adams and other members of the Boston Caucus to establish the Land Bank; this bank gave out paper money to borrowers, who mortgaged their property as security. While the Land Bank was popular among poor farmers, whose buying power was greatly increased, it was criticized by the colony's elite, who viewed it as an inflation scheme. The aristocrats complained to Parliament, who ordered the Land Bank shut down in 1741. Deacon Adams and his partners were deemed liable for the paper money already in circulation and were ordered to pay it back. This sent the deacon spiraling into ruinous debt.

In 1748, Samuel Adams inherited both his father's estate and debt. He was quick to challenge the debt, arguing that his father had been allotted a larger portion than other partners. The Massachusetts Legislature refused to listen and authorized Adams' creditors to seize his entire estate to satisfy the debt. Adams objected, arguing that the government had no right to take his property, especially since it was worth more than the supposed debt. He continued petitioning the courts while simultaneously chasing the sheriff and potential buyers off his property. Adams succeeded in dragging the proceedings on long enough for his creditors to lose interest and drop their claims. The incident disillusioned Adams with the government; he believed that Parliament had exercised arbitrary power by closing the Land Bank and that Massachusetts' colonial government had violated his rights by attempting to take his property.

Marriages

In 1756, Adams was elected to the post of tax collector. He proved inept at this job as well, often failing to collect taxes. While this made him popular among the city's taxpayers, he was personally liable for the missing funds and, by 1765, owed £8,000 in back taxes, although this debt was ultimately forgiven once he had become a popular political figure. Despite his perpetually bad finances, he still managed to get married in October 1749 to Elizabeth Checkley, a pastor's daughter. The marriage was a happy one, with Samuel writing that Elizabeth was "as sincere a friend as she was a faithful wife" (Schiff, 53). The couple had six children, only two of whom would live to adulthood: Samuel (b. 1751) and Hannah (b. 1756). In 1757, Elizabeth died while giving birth to a stillborn baby. The distraught Adams waited seven years to remarry, an unusually long period of grief in those days. He finally remarried in 1764 to Elizabeth Wells, or 'Betsy'. His second marriage lasted until his death, although it produced no additional children.

Opposition to Parliament

Around the time of Adams' remarriage, Parliament had decided to implement a series of direct taxes on the Thirteen Colonies, to help pay off the debt incurred by the British Empire during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). These included the Sugar Act (1764), which enforced a tax on the molasses trade, and the more egregious Stamp Act (1765), which placed a tax on all paper documents including newspapers, legal contracts, calendars, and playing cards. The colonists were taken aback by these sudden taxes; previously, Parliament had followed an informal policy of salutary neglect, allowing the colonies to govern and tax themselves. By implementing these direct taxes, Parliament was also tightening its authority over the colonies.

As subjects of the British king, the colonists considered themselves Britons, and therefore felt entitled to the so-called 'rights of Englishmen'; as guaranteed in legal documents such as the English Bill of Rights of 1689, as well as their own colonial charters, these included the rights to representative government as well as self-taxation. Since no American colonists were represented in Parliament, many wondered whether Parliament's attempt to tax them violated these rights. Adams, for one, argued that it did. With memories of the Land Bank fiasco certainly on his mind, he wrote in 1764 that 'taxation without representation' was not only unconstitutional but also dangerous to American liberties:

For if our trade may be taxed, why not our lands? Why not the produce of our lands and everything we possess or make use of? This we apprehend annihilates our Charter Right to govern and tax ourselves – it strikes at our British Privileges, which as we have never forfeited them, we hold in common with our fellow subjects who are natives of Britain: if taxes are laid upon us in any shape without our having a legal representation where they are laid, are we not reduced from the character of free subjects to the miserable state of tributary slaves?

(Cushing, 5)

Adams' bombastic, elegant prose struck a chord. Writing under the pseudonyms 'Vindex' and 'Candidus', he published similar essays in colonial newspapers like the Boston Gazette and quickly gained recognition among the Whigs, or Patriots, who opposed Parliament's taxes. By 1765, his influence was second only to James Otis Jr., a lawyer and member of a prominent political family. Otis and Adams started working closely with one another, and soon began attacking British policies and lambasting royal officials; in particular, they targeted Massachusetts Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson, with whom each man had a personal grudge (Adams partially blamed Hutchinson for closing the Land Bank). Their rhetoric helped paint Hutchinson as the architect of the colony's misfortunes, leading a mob to storm his house during the Stamp Act riots of August 1765. Though Adams did not partake in the riots, some have accused him of instigating them, citing his close association with the Loyal Nine, the group of political agitators that organized the mobs. The Loyal Nine was the precursor to the Sons of Liberty, of which Adams was a leading member.

Parliament repealed the Stamp Act shortly after the riots but doubled down by implementing the Townshend Acts (1767-68). Adams, in turn, intensified his attacks on Parliamentary authority and royal officials. In 1768, he and Otis drafted the Massachusetts Circular Letter, which called on all the colonies to coordinate in their opposition to the taxes; this was a major step toward the unification of the colonies. He also spearheaded a boycott of British imports and campaigned for Massachusetts merchants to sign non-importation agreements; those who did not were branded enemies of liberty, susceptible to be tarred and feathered by the rowdy Sons of Liberty, along with any other Loyalists. At the same time, Adams recruited John Hancock, Boston's wealthiest merchant, to the Patriot cause. While Adams has often been accused of manipulating Hancock in a similar manner that "the Devil is represented as seducing Eve" (Unger, 88), in truth, it was a symbiotic relationship; the popular Hancock could serve as a mouthpiece for Adams' words, while Adams could help Hancock undermine the taxes that were hurting his business.

Escalation

In 1768, British soldiers were sent to Boston to quell the discontent, providing excellent propaganda fodder for Adams. He wrote articles for the Boston Gazette, painting the soldiers as brutes who were there to oppress good Bostonians and ravish their women. This perspective heightened an already tense atmosphere, which culminated in the deaths of five Americans in the Boston Massacre of 5 March 1770. Adams wasted no time painting Boston as the victim of a vicious attack and joined with other city leaders in demanding the expulsion of British troops. Simultaneously, he realized that the soldiers who had perpetrated the massacre needed a fair trial, lest the Patriot cause lose all its credibility. For this purpose, Adams recommended that Josiah Quincy and his second cousin, John Adams, represent the soldiers at trial; all but two of the soldiers were eventually acquitted.

After the massacre and the simultaneous repeal of most of the Townshend Acts, it appeared to most Americans that the crisis was over. Many Patriot leaders removed themselves from politics, expecting things to return to the status quo. Samuel Adams was among the few to keep the revolutionary flame alive during this so-called 'quiet period'. By this point, he had eclipsed Otis and most other Patriots in his radicalism, having already come to believe that independence was necessary long before his associates reached the same conclusion. To this end, he worked to unite the colonies and, in 1772, worked with Arthur Lee of Virginia to create an intercolonial system of committees of correspondence, to better unify the colonies in their resistance. Adams worked tirelessly to keep the taxation controversy alive, leading an exasperated Governor Hutchinson to doubt "whether there is a greater incendiary [than Adams] in the King's dominion" (quoted in Boatner, 9).

Then, in May 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, which was intended to bail out the financially troubled British East India Company by granting it a monopoly on the sale of tea in the colonies. There was, however, one glaring problem; any tea sold by the company would include a Parliamentary tax. Adams was quick to fan the flames, pointing out that by purchasing the East India Company tea, the colonists would be implicitly agreeing that Parliament had the right to tax them. He succeeded in convincing many colonists that the Tea Act was a secret Parliamentary plot to enslave them. So, when three vessels carrying East India Company tea arrived in Boston Harbor, the Sons of Liberty refused to let them unload their tea; under British law, if the ships did not unload their cargo within 20 days, it was liable to be seized by customs officials and auctioned off.

On 29 November 1773, Adams hosted a meeting of thousands of Bostonians at Old South Meeting House, where a resolution was passed urging the ships to sail away without unloading their cargo. Governor Hutchinson, however, countered this by refusing to permit the ships to leave the harbor without unloading the tea and paying the duty. On 16 December, the night before the deadline, Adams hosted another meeting, in which he learned that Hutchinson had once again refused to let the ships set sail. Adams then announced that they had done "all they could for the salvation of their country" (Schiff, 240). At those words, between 30 and 130 men quietly left the meeting, disguised themselves as Mohawk Native Americans, boarded the ships, and dumped 342 crates of tea into Boston Harbor. Adams has long been credited with giving the signal that began the Boston Tea Party, although this claim has been disputed.

Founder

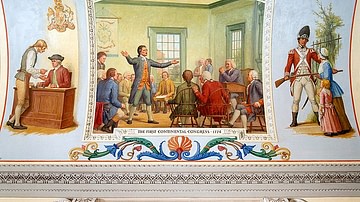

Parliament responded to the Boston Tea Party by issuing the Intolerable Acts, which closed Boston Harbor and suspended representative government in Massachusetts. In September 1774, colonial delegates met at the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where it was decided to keep the New England militias prepared for a potential conflict with British troops. Adams, his cousin John, and John Hancock were delegates at the Congress, leading the new British military governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Gage, to consider them enemies to royal authority. Fearing arrest, Adams and Hancock went into hiding in Hancock's childhood home in the town of Lexington. They were still there when, in the early morning hours of 19 April 1775, they were awoken by Paul Revere, who warned them that over 700 British regulars were on the road to Lexington, possibly to arrest them. Adams and Hancock left the town only hours before the Battles of Lexington and Concord were fought, igniting the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

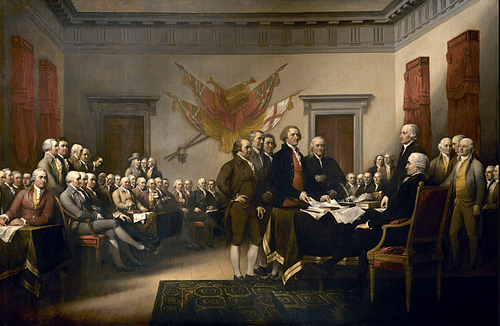

Adams and Hancock made their way to Philadelphia, where they joined the Second Continental Congress, which served as the provisional government of the rebellious colonies. Alongside John Adams, Patrick Henry, and the Lee family of Virginia, Samuel Adams led the radical wing of Congress, and helped spearhead the push for independence; after Congress' Olive Branch Petition was rejected by the king and the idea of independence was popularized by Thomas Paine, the radical Adams-Lee faction began to gather support. Finally, Congress voted for independence in July 1776, and Samuel Adams became one of the 56 men to sign the Declaration of Independence. He also helped draft the Articles of Confederation, which served as an early constitution for the United States.

Samuel Adams continued to serve in Congress, although his star power began to fade. He had a falling out with Hancock, whose ostentatious lifestyle contrasted with Adams' idea of a virtuous revolutionary; when Hancock retired from Congress in 1777, Adams voted against thanking him for his service. Despite being a skeptic of standing armies, Adams nevertheless served on the Board of War and urged Congress to pay soldiers bonuses to encourage them to re-enlist. In 1779, he helped draft the Massachusetts Constitution and resigned from Congress in 1781, shortly before the final American victory at Yorktown.

Postwar Politics

Adams returned to Massachusetts where he continued to wield some influence. He opposed letting previously banished Loyalists return to the state, fearing that their presence would undermine the fragile republic. In 1786, farmers in western Massachusetts launched an armed revolt in protest against taxes, known as Shays' Rebellion. Adams not only condemned the revolt but urged that the ringleaders be hanged; he believed that anyone who rebelled against the laws of a republic, instituted by the will of the people, should be executed. Hancock, serving as governor, disagreed and pardoned the rebels.

Although initially an opponent of the US Constitution, Adams changed his mind and was instrumental in its ratification in Massachusetts in 1788. He reconciled with Hancock and served under him as lieutenant governor in 1789; when Hancock died in 1793, Adams became governor and was elected to a full term the following year. By this point, his health had begun to fail, and he could no longer write due to tremors in his hands. He declined to seek another term and left office in 1797. Although he supported the policies of Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republican Party, he absented himself from the political spotlight. On 2 October 1803, Samuel Adams died at the age of 81, eulogized in Boston newspapers as "the Father of the American Revolution" (Schiff, 325).