Captain Samuel Bellamy, aka 'Black Sam' Bellamy (d. 1717), was a British pirate active during the Golden Age of Piracy (1690-1730). Bellamy’s final ship Whydah was wrecked off Cape Cod in a storm, and the pirate captain drowned along with almost all of his crew. The wreck was rediscovered in 1984, and many artefacts from it have since been rescued which collectively give a fascinating insight into both the plunder and equipment of an 18th-century pirate ship.

Early Career

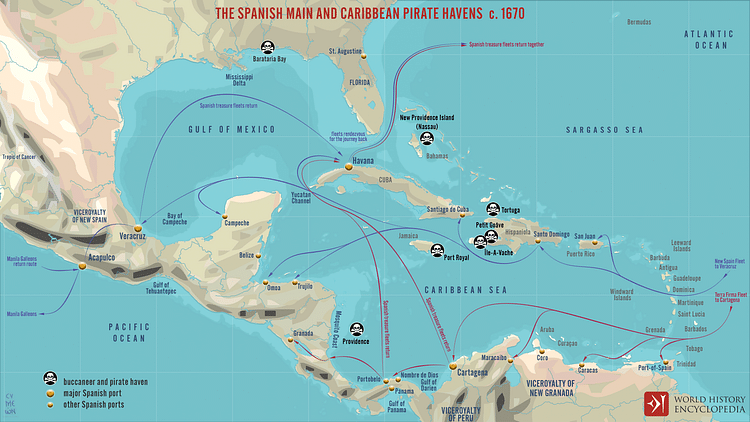

Few details of Samuel Bellamy’s early years are known. He was British and began his life of piracy as a crew member of Captain Benjamin Hornigold, active in the Caribbean and North Atlantic from 1716 to 1717. Bellamy was given a captured eight-gun sloop by Hornigold, the Mary Anne, and so his career as a pirate captain began around 1716. Hornigold decided to seek a royal pardon from the governor of the Bahamas, Woodes Rogers (1679-1732), and he subsequently turned pirate-hunter with some success. Hornigold died in a shipwreck off the coast of Mexico in 1719. Bellamy, meanwhile, continued to sail under the black flag, and he was voted by Hornigold’s crew to be their new pirate leader. Bellamy’s partner in crime was fellow captain, Olivier La Bouche, a Frenchman. Bellamy’s quartermaster was Paul Williams, who was later given command of a captured sloop.

The pirate group took many prizes near the Virgin Islands which included both French and British ships, the latter being a target Hornigold, at least according to legend, had refused to contemplate. Early in 1717, Bellamy’s and La Bouche’s ships were separated in a storm. La Bouche decided to change hunting grounds and prowled the coast of West Africa and then the Indian Ocean, but his ultimate fate is uncertain. Bellamy, meanwhile, roamed the waters between Haiti and Cuba in his 14-gun sloop Sultana.

The Wreck of the Whydah

In March 1717, Bellamy and Williams worked their ships in tandem to capture the slave ship Whydah in the Bahamas on its way back to England from Jamaica. The ship (spelt Whidaw in some sources) was named after the slave port in West Africa. It was a three-masted, 300-ton vessel built in London c. 1716. When Bellamy sailed across its bows, the Whydah was loaded with a very valuable cargo of gold, ivory, indigo, sugar, and rum. It was no easy catch and took Bellamy three days of pursuit to take it. The pirate took over the Whydah for his own flagship, adding more cannons to bring its heavy armament up to an impressive 28. Perhaps four more ships were plundered, and Bellamy added to his pirate fleet by taking one of these and promoting to its captain a man called Montgomery. Two more prizes were taken as the fleet headed north to Rhode Island. Bellamy obliged many captives to join his pirate crew, but only if they were not married men according to testimony from his crew at their trial.

Then disaster struck on 26 April 1717. That night, the Whydah ran aground in a storm off Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The ship lost its main mast and was dashed against rocks. Bellamy drowned in the storm along with almost everyone else. Just two men survived from a total crew of 146. At the same time, a second ship in the fleet ran aground, and only nine of that crew managed to clamber ashore at Orleans. For most of the survivors, their respite was but a brief one since they were soon captured and tried for piracy in October in Boston, Massachusetts. Seven of the men were hanged. Paul Williams had become separated from Bellamy during the fateful storm, but he returned to the site a few days later to salvage what he could that was of value. Williams’ search was made very difficult by the continuing bad weather and the fact the storm had spread some of the wreckage over an area of four miles (6.4 km). Bellamy’s treasure would have to wait for more modern, better-equipped treasure-seekers.

The wreck of the Whydah was rediscovered by Barry Clifford in 1984, and many recovery dives have been made on it ever since. The historian D. Cordingly records some of the items recovered from the wreck:

[Divers] brought up from the seabed an impressive quantity of coins, gold bars, and African jewelry. There are 8,397 coins of various denominations, including 8,357 Spanish silver coins and 9 Spanish gold coins, which together add up to 4,131 pieces of eight. There are 17 gold bars, 14 gold nuggets, and 6,174 bits of gold, and a quantity of gold dust. The African gold includes nearly four hundred items of Akan jewelry, mostly gold beads, pendants, and ornaments. (191)

Other artefacts, although more mundane, have given an invaluable insight into piracy and life at sea in the early 18th century. Items recovered include the ship’s bell, various types of ammunition, swivel cannons, fixed cannons, tools, and gaming pieces. A pistol was discovered still with its red silk sash attached, used by a long-gone pirate to make sure he did not lose such a valuable piece in the heat of battle and - who knows? - perhaps it even belonged to Captain Bellamy.

A General History of Pyrates

Bellamy is honoured with his own chapter in the celebrated pirate’s who’s who, A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, compiled in the 1720s. The book was credited to a Captain Charles Johnson on its title page, but this is perhaps a pseudonym of Daniel Defoe (although scholars are still debating the issue, and Charles Johnson may have been a real, if entirely unknown pirate expert). In this chapter, a speech of Bellamy’s is quoted in full, which may be entirely fictional but which has, nevertheless, become one of the most quoted of all pirate speeches. Bellamy speaks to a captain of a recently captured merchant vessel, one Captain Beer, and first explains that his crew has decided to sink Beer’s ship before justifying his life of crime:

I am sorry they won’t let you have your sloop again. for I scorn to do anyone a mischief, when it is not to my advantage; damn the sloop, we must sink her, and she might be of use to you. Though damn ye, you are a sneaking puppy, and so are all those who will submit to be governed by laws which rich men have made for their own security; for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they get by knavery; but damn ye altogether; damn them for a pack of crafty rascals, and you, who serve them, for a parcel of hen-hearted numskulls. They vilify us, the scoundrels do, where there is only this difference, they rob the poor under the cover of law, forsooth, and we plunder the rich under the protection of our own courage; had you not better make one of us, than sneak after the arses of those villains for employment?..You are a devilish conscience rascal, I am a free prince and I have as much authority to make war on the whole world, as he who has a hundred sail of ships at sea, and an army of 100,000 men in the field; and this my conscience tells me; but there is no arguing with such sniveling puppies, who allow superiors to kick them about deck at pleasure; and pin their faith upon a pimp of a parson; a squab, who neither practices nor believes what he puts upon the chuckle-headed fools he preaches to. (587)

Captain Beer was then deposited on a remote island and left to his fate. After some more pirating was conducted as far north as Newfoundland, Johnson/Defoe goes on to inform the reader that Bellamy met a particularly just end, tricked into running the Whydah aground. Bellamy was persuaded by a captive that, he knowing the treacherous part of the Americas’ eastern coast where they now found themselves, he could sail ahead in one the fleet’s ships and hang a lantern from his stern to show the other pirate ships the way. It turned out that this man was intent on revenge for his capture and so, waiting for the pirate crews to be all drunk one night, as they frequently were, he guided the fleet to a stretch of sandbanks and rocks where all were run aground. The prisoner escaped, but Bellamy, Williams, and their crews were all drowned. A handful of pirates survived from a third ship, but these were tried and hanged. Johnson/Defoe, not for the first time in one of his pirate tales, goes on to remind the reader that all these captured pirates were penitent of their crimes, fully comprehending the dire sins they had wantonly committed in the moments before they were about to meet their maker.