The Sand Creek Massacre (29 November 1864) was a slaughter of citizens of the Arapaho and Cheyenne nations at the hands of the Third Colorado Cavalry of US Volunteers under the command of Colonel John Chivington, resulting in casualties estimated at over 150 in the Native American encampment, which was in compliance with the policies of US officials.

Black Kettle (l. c. 1803-1868), chief of the Southern Cheyenne, had consistently sought peace with the White settlers since signing the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. He rejected the call to war of others – including Chief Tall Bull of the Dog Soldiers and Roman Nose (Cheyenne Warrior) – and continued to trust in the assurances of the representatives of the US government that the Cheyenne would be left in peace. These representatives were under the impression that Black Kettle spoke for all the Cheyenne in signing the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 or the Treaty of Fort Wise in 1861, but he had no control over other chiefs like Tall Bull (l. 1830-1869) or Roman Nose (l. c. 1830-1868), who continued to resist the encroachment of Euro-Americans on their lands.

Hostilities escalated in June 1864 with the Hungate Massacre, in which the killing of a White family was attributed to Cheyenne warriors. John Evans (l. 1814-1897), then governor of Colorado, sent word to the Native communities that any who were friendly toward the United States should seek safety near Fort Lyon, and all others would be considered hostiles. Black Kettle – along with other chiefs including White Antelope (l. c. 1789-1864), Little Wolf (l. c. 1820-1904), and Chief Niwot (Left Hand) of the Southern Arapaho (l. c. 1825-1864) accepted the invitation and moved their people to Big Sandy Creek, about 40 miles (65 km) northwest of Fort Lyon.

On the morning of 29 November 1864, Colonel John Chivington (l. 1821-1894) led the Third Colorado Cavalry in a surprise attack on the encampment – even though Black Kettle, as instructed, was flying the American flag and the white flag above his lodge – slaughtering over 150 innocent people, mostly young children, women, and the elderly. Afterwards, Chivington claimed this engagement was a great military victory against an armed alliance of Cheyenne and Arapaho until reports of survivors – like the Cheyenne-Anglo interpreter George Bent (l. c. 1843-1918) – and soldiers like Captain Silas Soule (l. 1838-1865) – contradicted him.

The ensuing investigation established the conflict as a massacre of innocents with only a small armed force of Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors in the camp killed defending themselves and their families. Still, the event was designated a "battle" by the press of the time and is often still referred to as such in the present day. In 2007, the area of the massacre was declared a National Historic Site, and, in 2014, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper gave an apology to the descendants of those murdered at Sand Creek; but the policies that made that massacre possible have never been acknowledged, and the US government has never offered a similar apology.

Background

The California Gold Rush of 1848 sent scores of miners and their families through the lands of the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Sioux, and others, disrupting their lives, scattering – and killing – the buffalo (the primary food source of the Plains Indians), and destroying the prairie with their wagons and cattle. Clashes between the Natives and settlers led to the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, establishing territories for Native American nations in the region which, according to this treaty, the United States had no claim to.

Black Kettle, and other chiefs, signed the treaty trusting in the word of the US delegates that they would not be bothered any further. The treaty was never honored by the White settlers or their government, however, and was completely discarded in 1858 during the Pike's Peak Gold Rush. When the Natives again fought to defend their lands, another treaty was offered – the Treaty of Fort Wise of 1861 – which the US government and its citizens paid no more attention to than the one they had presented to the people of the Plains in 1851. The Dog Soldiers – one of the military societies of the Cheyenne – responded to the invasion with armed resistance under their leader Tall Bull while Roman Nose led his own band in defense of Cheyenne lands in what came to be known as the Colorado War (1864-1865).

Although Black Kettle – and other 'peace chiefs' – rejected the course taken by Tall Bull and Roman Nose, they could do nothing to stop them. The Cheyenne had a representational government, the Council of Forty-Four, which made decisions for the whole nation, but the chief of each band was free to accept or reject their conclusions. The council had nothing to say regarding declarations of war which were the responsibility of individual chiefs of military societies. Black Kettle's signature on a treaty did not in any way bind Tall Bull to recognize it.

Hungate Massacre, Evans & Chivington

The Treaty of Fort Wise of 1861, rather than secure the lands of the Plains Indians from further encroachment, only restricted them to narrow tracts where they were expected to practice agriculture as defined by the US government, and, in return, they would be given adequate supplies and provisions. The promised goods never arrived, and the Natives began taking food, livestock, and whatever else they needed from surrounding settlements. Sometimes these goods were stolen quietly in the night, but other times by raiding parties such as those led by Tall Bull, Roman Nose, and other war chiefs.

On 11 June 1864, the Hungate family – Nathan and Ellen and their two young daughters Laura and Florence – were massacred and their home burnt in one of these raids. Their mutilated bodies were brought into Denver from the ranch where Nathan worked, sparking public outrage and calls for revenge. Governor Evans had earlier given Colonel John Chivington – then commanding the 1st Regiment of Colorado Volunteers – the freedom to kill any Cheyenne or Arapaho he saw in retaliation for raids in the area and, after the Hungate Massacre, this policy was continued without regard for whether those killed had anything to do with the Hungate incident. In fact, it was never determined who had killed the family, and it was never even established that the murders were the work of the Arapaho or Cheyenne.

As both Evans and Chivington had political aspirations that hinged on securing Colorado territory from "Indian attacks", they could not have cared less who had killed the Hungate family as long as they could blame it on Natives – easy enough to do since the Dog Soldiers and others were routinely raiding White settlements and homesteads – and so their policy of indiscriminate murder of Native Americans not only went unchallenged but was applauded. It should be noted, however, that if the treaties of 1851 and 1861 had been honored by the US government and White settlers, there would have been no need for the Dog Soldiers – or any others – to have launched raids in the first place.

In keeping with his policy already issued, however, Evans promised safety to any Native American bands that surrendered peacefully and sought refuge at Fort Lyon – then under the command of Major Edward W. Wynkoop (l. 1836-1891) who was sympathetic to the Native American cause. In September 1864, Black Kettle led his Southern Cheyenne, and Chief Niwot his Arapaho, to Fort Lyon where they were soon after told to move their camps to Big Sandy Creek, about 40 miles (65 km) northwest of the fort. In November, Major Wynkoop was reassigned to Fort Riley, Kansas, and was replaced at Fort Lyon by Major Scott Anthony who shared none of Wynkoop's sensibilities toward the Arapaho and Cheyenne and approved of the policies of Evans and Chivington in killing any Native they happened upon.

When Anthony announced the plan to attack the encampment at Sand Creek, Lt. James Connor, Lt. Joseph Cramer, and Captain Silas Soule objected on the grounds that these were innocents who were in full compliance with Evans' policy. Chivington is said to have threatened Soule's life if he did not comply, but Anthony took another approach, assuring Soule, Cramer, and Connor that Chivington was leading his men against hostiles – presumably near the encampment – not against the people of Black Kettle or Chief Niwot.

Sand Creek Massacre

On the morning of 29 November 1864, Chivington arrived at the Sand Creek encampment and gave the order to fire. Captain Soule and Lt. Cramer refused and had their men stand down from their positions. No other soldiers are on record as objecting to the massacre. Scholar Ari Kelman gives Soule's account of the massacre, sent afterwards in a letter to Major Wynkoop:

Soule later recalled, "we arrived at Black Kettle's and Left Hand's camp at day light." After Chivington's men opened fire without warning, a soldier from the 1st Colorado and an interpreter trading in the camp "ran out with white flags," signaling that the Indians were peaceful. The troops paid no attention." "Hundreds of women and children were coming towards us," Soule remembered, "getting on their knees for mercy." Major Anthony responded by shouting, "Kill the sons of bitches." A horrified Soule related in his letter to Wynkoop that he had "refused to fire." Instead, after taking his company across the creek, away from the melee, Soule watched, appalled, as artillery barraged the Native people: "Batteries were firing into them, and you can form some idea of the slaughter." "When the Indians found that there was no hope for them, they went for the creek and buried themselves in sand and got under the banks." Here, Soule offered a different view of the fortifications that Chivington often cited as definitive proof that he had attacked a village overflowing with hostile Indians itching for a fight. [Soule further added], "There was no organization among our troops, they were a perfect mob."

(23)

According to a letter from Lt. Cramer to Wynkoop, "Black Kettle said, when he saw us coming, that he was glad, for it was Major Wynkoop coming to make peace" (Vasicek, 2). The American flag and white flag of truce were both flying, and Black Kettle told his people to stand in a circle beneath them to show they were peaceful, but Chivington's troops had already started firing and would not stop. Robert Bent, brother of George Bent, had been captured by Chivington and forced to guide the troops to the camp. He later reported:

I saw the American flag waving and heard Black Kettle tell the Indians to stand around the flag, and there they were huddled – men, women, and children. I also saw a white flag raised. These flags were in so conspicuous a position that they must have been seen. When the troops fired, the Indians ran, some of the men into their lodges, probably to get their arms…I think there were 600 Indians in all. I think there were 35 braves and some old men, about 60 in all…the rest of the men were away from camp, hunting.

(Vasicek, 2)

The massacre went on for seven hours – White Antelope and Chief Niwot were both killed – and many of the soldiers returned the next morning to finish off any survivors. Those who had managed to hide during the slaughter – including Black Kettle and his wife, Chief Morning Star, and Charles, Julia, and George Bent – had gone up the creek to find safety with other bands. George Bent reported:

Everyone was crying, even the warriors and the women and children…Nearly everyone present had lost some relations or friends, and many of them in their grief were gashing themselves with their knives until the blood flowed in streams.

(Vasicek, 4)

Chivington and Anthony, meanwhile, had led their troops back to Fort Lyon where Chivington quickly sent word of his great victory to his superior, General Samuel Curtis, proudly noting how "at daylight this morning we attacked a Cheyenne village of 130 lodges, from 900 to 1,000 warriors strong" (Kelman, 9). He then drafted similar letters which were quickly sent to the editors of the newspapers in Denver, characterizing the massacre as a "battle" in which his gallant soldiers had overcome heavily armed Cheyenne and Arapaho who had fortified their camp against the US government that had so kindly offered them safety.

This is the version of the event that was then reported by other newspapers across the country in December 1864 and would later be defended once the truth of what happened at Sand Creek began to come out by the end of that month. This is also the version of the event that colors interpretations of it today which continue to refer to it as a "battle" when it was not.

Aftermath & Investigation

Before the end of December 1864, there was already enough evidence to counter Chivington's account of the "battle" of Sand Creek, and there was already a pushback by Chivington's supporters against the allegations of a "massacre" even before President Lincoln, Congress, and the War Department concluded in January 1865 that these allegations were serious enough to warrant a formal investigation. Chivington supporters denied the claims of a massacre and defended the event as a "battle", however, helping to establish that definition of the event. A piece from the Rocky Mountain News in Denver from 30 December 1864 reads:

The affair at Fort Lyon, Colorado, in which Colonel Chivington destroyed a large Indian village, and all its inhabitants, is to be made the subject of congressional investigation. Letters received from high officials in Colorado say that the Indians were killed after surrendering, and that a large proportion of them were women and children.

Indignation was loudly and unequivocally expressed, and some less considerate of the boys were very persistent in their inquiries as to who those "high officials" were, with a mild intimation that they had half a mind to "go for them." This talk about "friendly Indians" and a "surrendered" village will do to "tell to marines," but to us out here it is all bosh.(Sand Creek Massacre Editorials)

The formal investigation went ahead, however, and it was concluded, based on eyewitness accounts of men like Silas Soule, that the conflict at Sand Creek had been a massacre of mostly unarmed Natives. Chivington resigned from the military, and he and Evans abandoned their political goals (Evans was removed from office), but no one was ever prosecuted for the Sand Creek Massacre. Silas Soule, who testified against Chivington, was murdered in Denver on 23 April 1865 by Chivington's supporters. He is remembered by the Cheyenne and Arapaho today as a hero.

The massacre broke the Cheyenne leadership as eight of the Council of Forty-Four had been killed but, of equal significance, it seemed clear to many Cheyenne that their leadership had been wrong to trust the US officials and war chiefs like Tall Bull and Roman Nose had been right. Black Kettle lost prestige to Tall Bull but still continued to seek peace with the US government and its citizens. None of the Cheyenne and Arapaho raiders were present at Sand Creek the morning of the massacre, and Tall Bull and Roman Nose continued on as they had before until Roman Nose was killed at the Battle of Beecher Island in September 1868 and Tall Bull at the Battle of Summit Springs in July 1869.

Conclusion

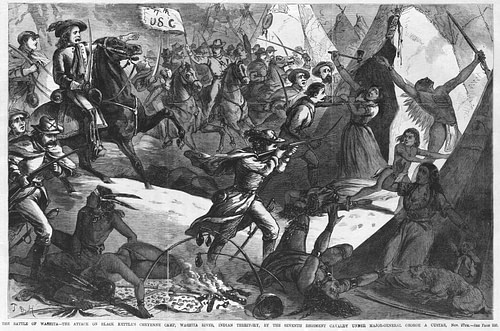

By the time of Tall Bull's death, Black Kettle and his wife, along with 60-150 others, had been murdered by troops under Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876) at the Washita Massacre on 27 November 1868 – also designated a "battle" by US authorities – and Cheyenne resistance to US policies of expansion was broken. Later efforts by the Northern Cheyenne chiefs Morning Star (Dull Knife, l. c. 1810-1883) and Little Wolf were crushed in 1878. The Cheyenne people survived, however, and remain a proud Native American Nation today.

The dead of the Sand Creek Massacre continue to be honored by their descendants as, every November, they join in the Sand Creek Spiritual Healing Run/Walk – a 173-mile (278 km) event in which participants follow the route taken by the US troops after the massacre from the site to Denver. As Kelman notes, "The Sand Creek Massacre is not an event relegated to the past, but is a very real part of the Cheyenne people's contemporary identity" (130), and the event is commemorated in the same way people remember and observe 9/11.