Scipio Africanus Major (l. 236-183 BCE) received his epithet due to his military victories in Africa which won the Second Punic War for Rome against Carthage. He is also known as Scipio the Elder. He was born Publius Cornelius Scipio in 236 BCE. His family was of Etruscan descent and of the Patrician upper class.

His father, also Publius Cornelius Scipio, was a Roman consul and, in 218 BCE, brought his son along with him on campaign to face the great Carthaginian general Hannibal in northern Italy. Although ancient writers have reported that, in his later years, Scipio wrote an autobiography and many other works, these have been lost and all that we know of his life are the details of his military victories and his actions as a statesman.

Hannibal's Victories

At the Battle of the Ticinus River, Hannibal's troops so out-maneuvered the Roman forces that his father was surrounded. His son rode into the battle, shaming the Roman troops who were hesitating, and rescued his father. At the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE, a disastrous defeat for the Romans, Scipio experienced first-hand the brilliance of Hannibal's tactics as the Carthaginian army surrounded and decimated over 44,000 Roman troops.

Believing that Hannibal could not be defeated by traditional arts of war, Scipio's father thought it the best strategy to cut off Hannibal's supply line from Spain. He therefore took his son and joined with his brother, Gnaeus Scipio, who was fighting Hannibal's brother, Hasdrubal Barca (l. c. 244-207 BCE), at the border of the Spanish territories of Rome and Carthage. Both Scipio's father and Gnaeus were killed in action at the Battles of Baetis Valley (also known as The Battle of the Upper Baetis) and Scipio returned to Rome.

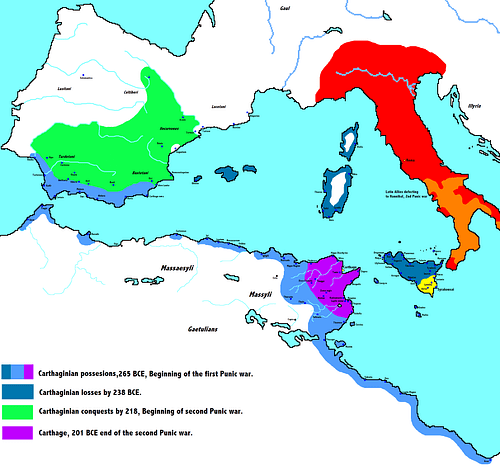

The Second Punic War

The Carthaginians under Hasdrubal now held Spain without contest and the Roman senate could not tolerate such a situation. Hannibal had started the Second Punic War through his attack on the city of Saguntum, a Roman ally, situated south of the Ebro River in Spain, and now it seemed his brother was free to do as he pleased throughout the region while Hannibal crossed the Alps to invade Italy.

The senate needed a general of considerable ability to send against Hasdrubal but no one wanted the job as the campaign seemed to be a death sentence. Though only twenty-four years old, thought too young to command, Scipio volunteered for the position and left Rome with 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry to meet Hasdrubal's forces numbering over 40,000 strong.

Scipio landed in Spain at the mouth of the Ebro River and immediately took action. He marched toward Carthago Nova and lay siege to the city which was thought impregnable owing to the strong fortifications and also the natural defense of a lagoon (or marsh) which prevented attack from one whole side of the city's walls.

Through intelligence reports picked up during his march, Scipio learned that the lagoon was subject to a significant drop in level owing to the ebb of the tide. This traditional view of the taking of Carthago Nova has been challenged, notably by the scholar Benedict J. Lowe, who claims it is far more likely the "lagoon" was a salt marsh utilized by Carthago Nova for harvesting salt from the sea.

This marsh's water level would have been adjusted by sluices which let water into and out of the marsh and so Scipio, far from relying on the whims of the tide, simply drained the marsh to allow his troops to cross it. He would have counted on the defenders of the city being distracted by his assault on the front gate and also neglecting to guard the walls overlooking the marsh in the belief that no attack could come from that direction. Scipio sent a column of 500 soldiers through the shallow water who breached the walls and took the city.

The Roman historian Livy tells the story that, presented with a beautiful woman as a war prize by his troops, Scipio graciously refused her and sent her back to her fiancé along with the ransom money which her family had paid for her release. He would continue to maintain this practice of clemency and graciousness throughout his campaigns, portraying himself and Rome as liberators instead of conquerors.

Battle of Baecula

At the Battle of Baecula in 208 BCE, Scipio defeated Hasdrubal's superior forces and drove him from the field using tactics he had learned from Hannibal. Hasdrubal left Spain and crossed the Alps to join his brother in Italy and end the war by taking Rome. Before he could join his forces with Hannibal's, however, was defeated by a Roman army under the brilliant command of Gaius Claudius Nero (c. 237-c.199 BCE) at the Metaurus River in 207 BCE. Hasdrubal was killed in action and his forces scattered. Spain was now a colony of Rome.

Scipio then asked the Roman senate for supplies and an army to march on Carthage itself, believing, rightly, that if Carthage were threatened then Hannibal would be recalled from Italy to defend it. The Roman senate refused the request and so Scipio raised an army himself. According to the historian Durant, “The people admired him not only because he was handsome and eloquent, intelligent and brave, but pious, courteous, and just.” Scipio then threatened the Roman senate with an appeal to the Roman people for support of his campaign and they, fearing his popularity, gave him command of Sicily. Using Sicily as his base of operations, Scipio invaded North Africa in 205 BCE. Allied with the Numidian King Masinissa, Scipio defeated Carthage's ally Syphax and took the city of Utica. As he had expected, Carthage recalled Hannibal from Italy to save the city.

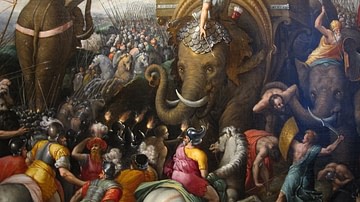

Battle of Zama

At the Battle of Zama, in 202 BCE, fifty miles south of Carthage, Scipio defeated Hannibal. It was the only battle Hannibal lost since assuming command of the Carthaginian forces but it was a pivotal loss. Scipio had long been learning from Hannibal's tactics and knew them well. When Hannibal sent his elephants charging against the Roman lines, Scipio revealed that he had formed them in columns, allowing the elephants to pass harmlessly through the alleys opened by his ranks.

Further, he had his musicians sound their horns loudly and bang on drums which so startled the elephants that many of them panicked and turned back to trample Hannibal's troops. The cavalry forces of Masinissa and Scipio's old friend and general Gaius Laelius then fell upon the Carthaginian cavalry, driving them from the field and back beyond the Carthaginian lines. Scipio then advanced his forces, broke Hannibal's front line, and, at the same time, the cavalry of Laelius and Masinissa returned to fall upon the Carthaginian rear.

Around 20,000 Carthaginian forces were killed as opposed to 1,500 Romans. Hannibal fled back to Carthage and urged surrender, thus ending the Second Punic War. In adapting Hannibal's tactics, and using his own strategies against him, Scipio changed the way Roman forces would fight from Zama onwards.

Senate Indictments & Retirement

Back in Rome, Scipio's political enemies sought to harass him through petty legal means such as accusing his brother Lucius of accepting bribes and misappropriating funds. Scipio tore up the account books as well as the indictment and, on the floor of the senate, asked why there was so much concern over so small an amount of money when he had negotiated the peace with Carthage and brought so much treasure to Rome.

Senatorial persecutions continued in further small measures against him and, in c. 185 BCE, he retired to his estate in Liternum, dying in 183 BCE (the same year in which Hannibal died). Disgusted with the Roman government's ingratitude, he left instructions that he be buried near his estate and, according to ancient writers, had `Ungrateful fatherland – You will not even have my bones' inscribed on his tomb.

Scipio Africanus is remembered, along with Alexander the Great, Hannibal, and Julius Caesar, as one of the greatest military minds of the ancient world. He never lost a single engagement while the army was under his command and behaved chivalrously toward those whom he defeated. In negotiating the peace with Carthage, he left her those holdings she had in Africa, pardoned Hannibal (which was largely the cause of his later persecutions by upper class Romans) and let the city keep ten warships to protect her trade in the Mediterranean region.

In doing so, he followed the policy which he had initiated in Spain of defeating hostile forces and then initiating healing through clemency. Scipio believed that he was favored by the gods and that he should return that favor by living an impressive life. The record of history shows that he more than succeeded in doing so and left a lasting name as a great general and an honorable man.