Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554 CE) was an Italian Renaissance architect, painter, and scholar. His most successful building design is the classically-inspired Château d'Ancy-le-Franc in France. Serlio's lifetime of scholarship came together in his Seven Books on Architecture, a hugely influential theoretical and practical work. In it, Serlio categorised ancient classical buildings, canonised the five classical orders, pioneered the profuse use of illustrations in such books, and greatly influenced architects across Europe, especially regarding doorways and giving ideas that could easily be copied by any good stonemason.

Early Life

Sebastiano Serlio was born in Bologna, Italy, on 6 September 1475 CE. His father trained him as a painter, and he showed a particular interest in perspective. Not a great deal is known about Serlio's personal life except that he married and had several children. In 1514 CE he moved to Rome, where he became the assistant of the Sienese architect and painter Baldassare Tommaso Peruzzi (1481-1536 CE), who was actually younger than Serlio. Peruzzi worked on many projects, including the new St. Peter's Basilica in 1520 CE, and he owned a large collection of architectural drawings that his assistant would later make excellent use of. Serlio and Peruzzi left Rome in 1527 CE and visited Venice together. It was in this period that Serlio began writing his great series of treatises on architecture that he would work on for the rest of his life.

Move to France

In 1541 CE Serlio left Italy for France, where he worked for the king, Francis I of France (r. 1515-1547 CE) on the design and construction of the Palace of Fontainebleau. Not a great deal of the palace can be securely attributed to Serlio except a monumental doorway, the Grand Ferrara. Serlio had built a chateau near Fontainebleau for the Cardinal of Ferrara, but it has not survived complete.

A more lasting and impressive contribution to French architecture is Serlio's Château d'Ancy-le-Franc in the Yonne department of north-central France. Serlio worked on the chateau from 1544 to 1546 CE. It was then completed according to Serlio's original plans but without his direct involvement. The chateau was built for Comte Antoine de Clermont-Tonnerre, and the architect conceived it as a non-functional fortress fit for a modern prince. The four wings and four massive square towers enclose an internal courtyard. A classical touch is the pilasters on either side of the many windows, although they are not as regularly spaced as is usual in Italian buildings. In keeping with the cooler climate with respect to Italy, the roofing has the traditional steep slopes seen in buildings of northern France. His best-surviving work as an architect, the chateau shows Serlio's use of harmonious decorative restraint, use of shadow effects, and a blending of local and classical tradition.

Seven Books on Architecture

Serlio's great contribution to Renaissance literature on the arts is his Tutte l'opera d'architettura, et prosepetiva, or Complete Works on Architecture & Perspective. This work consisted of six volumes, which were published (not in order) between 1537 and 1551 CE. After Serlio's death, a seventh volume was published in 1575 CE. The complete work, often called Seven Books on Architecture, not only covered the surviving buildings from antiquity and contemporary architectural theory but, unlike most other works on the subject, it also included practical advice for architects based on models.

The Seven Books on Architecture covers the following topics:

- Book I - geometry

- Book II - perspective

- Book III - antiquities

- Book IV - the five classical orders

- Book V - churches (described by Serlio as temples)

- Book VI - gateways and domestic architecture

- Book VII - a consideration of common design problems

An eighth book was added to the list in the 20th century CE following the discovery of a manuscript now in Munich. This last volume covers the description of a military camp by the 2nd-century BCE Greek writer Polybius.

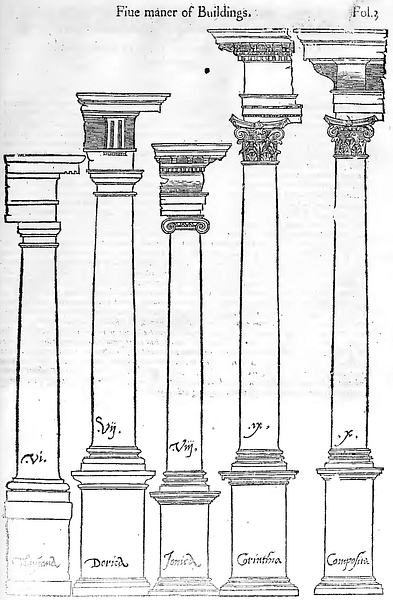

Another new feature for such a work was the inclusion of a great many detailed and accurate woodcut printed illustrations, drawn by himself, Peruzzi, and Donato Bramante (c. 1444-1514 CE). Indeed, the book is much more a series of illustrations connected by text than a prose work with a sprinkling of pictures.

In his work, Serlio famously formalised the classification of the five architectural orders, the fifth having first been identified c. 1450 CE by the architect and scholar Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472 CE). These orders are: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and the fifth, Composite (a mix of Ionic and Corinthian elements), then best seen, according to Serlio, in the top storey of the Colosseum in Rome. The canonisation of the orders made them into a sort of architectural grammar that subsequent architects have used and reacted to ever since. Their importance to Serlio is indicated by their illustration at the very beginning of his book, a decision copied by almost every other architectural scholar for the next two centuries.

Hugely popular and influential, Serlio's magnum opus did not meet approval in all quarters. The architect Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo once lamented that Serlio's work was read by so many people that he had consequently produced "more hack architects than he had hairs in his beard" (Hale, 298). This was no doubt a result of Serlio's effectiveness as an author since using the books, a patron with time, money, and a useful stonemason could reproduce just about any building style they wished. The consequence of this dissemination of ideas did often result in hybrid buildings which oddly mixed classical elements of architecture with those traditionally used in that particular geographical area, especially in England and France.

Death & Legacy

Serlio died in Fontainebleau, France, in 1554 CE. His book on architecture continued to be popular long after his death and was of particular interest to architects of the Neo-Classical style. The 50 illustrations of highly decorative doorways in the penultimate volume of his book were especially popular with Mannerist architects, particularly in Northern Europe. Indeed, Serlio's Seven Books was translated into English in 1611 CE, as well as several other European languages, including German, Spanish, Dutch, and Flemish. In this way, Serlio's ideas and reputation as the foremost cataloguer of architecture past and modern spread across Europe. In short, as the architectural historian J. Summerson put it, Serlio's collective works became the bible for all subsequent Renaissance architects:

The Italians used them, the French owed nearly everything to Serlio and his books, the Germans and Flemings based their own books on his, the Elizabethans cribbed from him and Sir Christopher Wren was still finding Serlio invaluable when he built the Sheldonian at Oxford in 1663. (11)

Serlio proved influential in more minor and less obvious areas such as the use of perspective in model and painted scenery for theatre stages. Using a single vanishing point, the scenery treated the audience to a far more realistic background, for example, a street rising away from the actors who stood before it. The architect's work even enjoyed a revival in other continents after Spaniards took his book and copied elements of it in the buildings they erected in Mexico and Peru while Jesuit missionaries did the same in India and other parts of Asia.