The Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9) once again saw the British East India Company defeat the Sikh Empire in northern India. The war, which started off as a rebellion against British colonial rule, included the high-casualty Battle of Chillianwala, but the conflict was finally won by the EIC with a decisive victory at the Battle of Gujrat in February 1849.

The EIC & the Sikh Empire

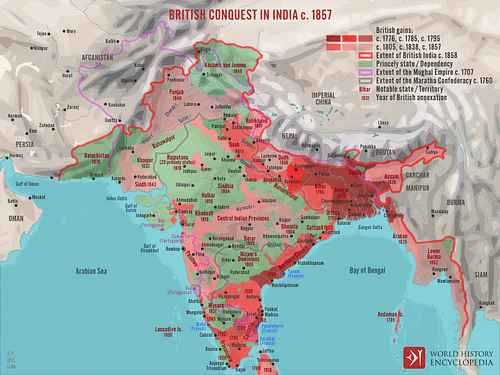

The British East India Company had been grabbing territory since its victories at the 1757 Battle of Plassey and the 1764 Battle of Buxar, which gave the British a vast and regular income in local taxes, besides other riches. The EIC kept on expanding and defeated the southern Kingdom of Mysore in the three Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799) and the Maratha Confederacy of Hindu princes in central and northern India in the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819). Next came expansion in the far northeast and more victories in the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-1815) and the three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824-1885). The next and final target of the EIC was northwest India and the Punjab, the heartland of the Sikh Empire.

The Punjab, located in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, is an area which today covers parts of Pakistan and India. The Sikh Empire had risen due to the gradual decline of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857). Sikh territories were divided between 12 misls or armies, each led by a chief who collectively formed a loose confederation. The greatest of Sikh leaders was Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), the 'Lion of Lahore'. He forged the Sikh Empire by modernising the army and conquering Multan and Kashmir (1819), Ladakh (1833), and Peshawar (1834). This expansion rang alarm bells in the offices of the East India Company, especially after their failure in the First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-42) to the north.

In 1839, the Sikhs, Afghans, and British signed a treaty to protect existing borders. Ranjit Singh died in June 1839, and political turmoil weakened the Sikh government's control over its own army. Rajit Singh's youngest son, Duleep Singh (l. 1838-1893), was selected as the new Sikh ruler in 1843, but as he was but a child, his mother, Jind Kaur (aka Rani Jindan, d. 1863), ruled as regent. Jind Kaur supported a military escapade against the British since, even if the Sikhs lost, this would cut the army down to size, perhaps ending the interference of the generals in government affairs and certainly reducing the threat of a military coup.

The EIC exploited the turmoil and conquered the Sindh province (southwest of the Punjab) in 1843. Confident that some of the Sikh misls in the east supported closer ties with the EIC, the British prepared for war in the Punjab and amassed an army of 40,000 men to the southeast of the Sikh state. In the wider world of empires, the British no longer considered the Sikh Empire a useful buffer zone in case of expansion of the Russian Empire into Afghanistan and northern India – the so-called Great Game. The Sikhs would now have to fight the seemingly unstoppable armies of the East India Company.

The First Anglo-Sikh War

The First Anglo-Sikh war broke out when a large Sikh army crossed the Sutlej River into EIC territory on 11 December 1845. Although the Sikh army was well-trained and well-equipped, particularly its artillery arm, it suffered defeats in all four major battles of the war: the Battle of Mudki on 18 December 1845, the Battle of Ferozeshah on 21-22 December, the Battle of Aliwal on 28 January 1846, and the Battle of Sobraon on 10 February. With the exception of Aliwal, all the battles resulted in a high number of casualties for both sides. While the EIC troops had been courageous and disciplined, the Sikh losses were in no small part because several of the top Sikh commanders in the field had one eye on what their positions would be should a regime change come about. Time and again, defensive tactics were used when a more aggressive use of cavalry might well have gained the Sikh army a victory. The ordinary Sikh troops and the misls felt that they had been badly let down by the generals, particularly Tej Singh (1799-1862), the Sikh commander-in-chief, and Lal Singh (d. 1866), both of whom gained prominent positions under the new British rule. Many felt they should have another crack at the British, especially given the harsh terms of the peace treaty which ended the first war.

Causes: The Treaty of Lahore

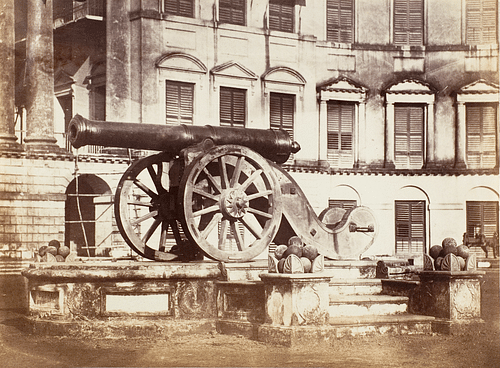

Under the terms of the Treaty of Lahore, signed on 9 March, the Punjab became a 'sponsored state', and parts of the Sikh Empire – territories south of the Sutlej river – came under direct EIC rule. Daleep Singh remained nominally the official Sikh Maharaja but under the watchful gaze of a British resident and a Council of Regency, which included the two EIC-sympathetic generals Tej Singh and Ranjodh Singh. The Sikh army was permanently reduced, all its cannons were confiscated, and it could no longer recruit foreign mercenaries. The EIC received a massive indemnity payment; they also took over Jammu and Kashmir (as part payment of the indemnity). Given these harsh terms, those militant Sikhs who wanted to restart the war argued that they had little to lose and much to gain if they could defeat the EIC. The militarists gained sympathy not only from thousands of former soldiers who had lost their jobs with the disbandment of the Sikh army but also from those members of society who had lost their positions under the new British regime. There were also many who resented the steady erosion of traditional religious and cultural practices. Another sore point was the exile of Jind Kaur in August 1847, who was separated from her son and kept in the fortress of Sheikhapur. The rebels became increasingly organised and chose as their figurehead Mul Raj, the former governor of the fortified city of Multan.

The Second War

The Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9) began in April 1848 and was largely fought in the south and west of what had once been the Sikh Empire. The Second Anglo-Sikh War involved the following key battles:

- Siege of Multan - April 1848 to 22 January 1849

- Battle of Ramnagar - 22 November 1848

- Battle of Sadulapur - 3 December 1848

- Battle of Chillianwala - 13 January 1849

- Battle of Gujrat - 21 February 1849

The spark that set off the second war was the murder in April of two British officers at Multan (aka Mooltan) by two deserter soldiers of the garrison. The EIC victims were a Lieutenant William Anderson and no less a figure than the Resident Patrick Vans Agnew. The city was then taken over by rebels. The EIC sent a force to retake Multan in May-June, but, only 5,000 men strong, it was too small to be effective. This initial reaction did at least contain the revolt and prevent it from spreading to other forts and cities. Then a larger EIC army was sent to besiege Multan in August-September, but its significant Sikh contingent joined the rebel cause, and the remaining core was obliged to withdraw. This debacle only encouraged more Sikhs to join the rebellion. The wider EIC response was to prudently wait until the unbearable heat of summer (deadlier to a British soldier than a Sikh bullet) was over and to meanwhile take control of several forts in the Punjab, but this only escalated the level of local resistance to British rule. The rebellion was now spreading across the Punjab.

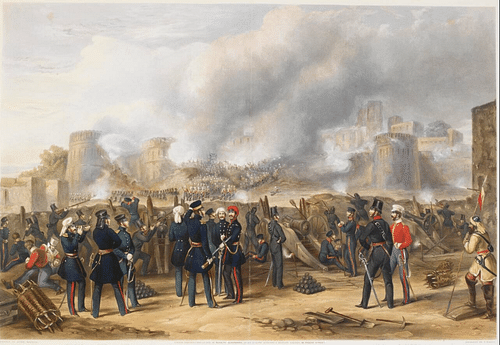

The Storming of Multan

In September and October, the EIC assembled two large armies to be sent to the Punjab to regain control there. One army was sent to recapture Multan and the other to the trouble-spot north of Lahore. Once again, the EIC found itself embroiled in a messy war of occupation. Multan, in particular, proved a tough old nut to crack with its formidable fortifications:

... a hexagonal wall 40 to 70 feet high ... A ditch 25 feet deep and 40 feet wide is at the front side of the wall besides which is a glacis ...Within the fort, and on a considerable elevation stands the citadel, in itself of very great strength. The ramparts bristle with eighty pieces of ordnance. (Holmes, 375)

Through December, Multan was steadily encircled, and the EIC positioned its big guns to blast the fortress, as here described by John Clark Kennedy:

Such a curious sight! First came the escort and the twenty-four pounders each drawn by twenty magnificent bullocks with an elephant behind each one. This put down its head and gave the gun a shove whenever they got to a steep place.

(Holmes, 381-2)

After the artillery had its say, first destroying the enemy cannons and then concentrating on pounding the city's walls, the infantry pressed to gain entry into the fortified city. In an attack on 4 January, the EIC army broke into the city but was then required to fight street by street until it came to the city's inner fortress, where 3,000 Sikh soldiers prepared to fight to the death. The fortress was finally taken on 22 January. There followed a brutal round of reprisals and looting, which involved the murder of women and children.

Battle of Chillianwala

On 13 January 1849, an EIC army of 14,000 men was led by the commander-in-chief Lieutenant-General Sir Hugh Gough (1779-1869) to face a Sikh army commanded by Sher Singh Attariwalla. Gough was a crusty old veteran who led from the front; he had gained victory in the First Anglo-Sikh War and personally led the armies at the bloody battles of Ferozeshah and Sobraon. Gough had won a narrow victory at the Battle of Ramnagar in this second war – essentially a confrontation of cavalry – but his reputation for throwing men at well-built defences meant that his own officers struggled to remain loyal to his command decisions. Gough showed no signs of improvement at Chillianwala, and once again, he ordered infantry charges in the face of a brutal Sikh artillery barrage and even fiercer musket fire. The 24th Regiment lost half its numbers, an appalling loss for the warfare of this period. Elsewhere on the battlefield, the EIC troops had more success, but the Sikhs, as usual, fought tenaciously, and as the sun set there was still no sign of a clear victor. Sher Singh requested a negotiated conclusion to the battle but was refused; he then ordered a withdrawal of his troops to fight another day. Having lost one-quarter of his men, Gough did not risk a pursuit.

Chillianwala was such a catastrophe in lives lost that General Gough came in for severe criticism back in Britain. As a result, the directors of the East India Company replaced Gough as commander-in-chief of the Indian army with Sir Charles Napier. However, by the time Napier arrived in the subcontinent, the next battle, still with Gough in charge, had already taken place and victory won.

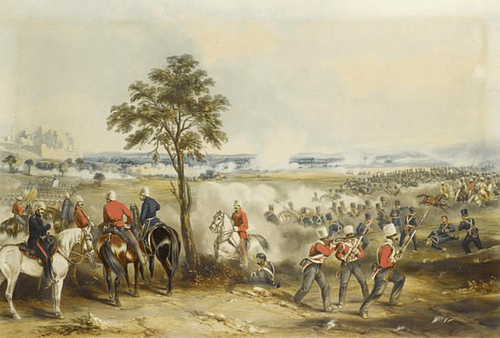

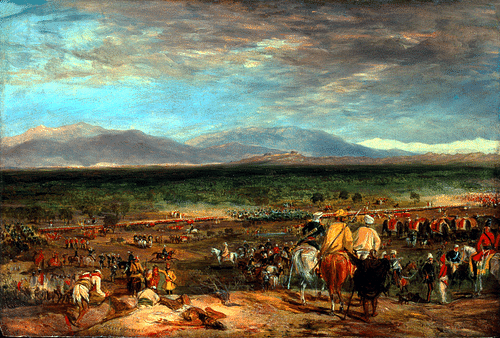

Battle of Gujrat

The two sides clashed again by the banks of the Chenab river near Gujrat (aka Gujarat or Goojerat) on 21 February 1849. Gough again commanded the EIC army and Sher Singh the Sikhs. Gough had the advantage of a large reinforcement arriving from the completed campaign against Multan so that he now commanded a very impressive 23,000 men.

Gujrat became known as 'the battle of the guns', as Gough finally changed his tactics from favouring infantry charges with fixed bayonets to better using his superiority in artillery, about 100 cannons to the Sikhs' 50. For two hours, the EIC cannons blasted away at Sher Singh's army, which was entrenched in excellent defensive fortifications. The Sikh gunners made the mistake of firing too early before the enemy was within range. The EIC infantry and light cavalry was then sent in and did not suffer the heavy losses typically seen in these two Sikh Wars. The EIC cavalry then mopped up the retreating Sikh infantry in a textbook combination use of artillery, cavalry, and infantry. As in most of the battles in this war and its predecessors, the Sikhs had paid dearly for a defensive strategy instead of attacking the enemy using their own cavalry. The courage of the Sikh commanders may have been in question but not the ordinary Sikh soldiers, as here described by private John Ryder:

We took every gun we came up to, but their artillery fought desperately; they stood and defended their guns to the last. They threw their arms round them, kissed them, and died. Others would spit at us, when the bayonet was through their bodies.

(Holmes, 343)

Gough's army then continued to round up Sikh rebel soldiers at Rawalpindi and Peshawar through March. The remaining Sikh forces elsewhere in the Punjab were obliged to hand over their weapons. As in the first war, the EIC had won the battles and the war, but only just, and at a high cost in men and material.

Aftermath

The British annexed the whole Punjab in March 1849, it was made a province of British India, and colonial administrators took over, notably John (1811-79) and Henry Lawrence (1806-57). Kashmir had already been given (at a price) to the Raja of Jammu for his support in the war, a territorial separation that would have lasting consequences. Duleep Singh was exiled to England where he was joined by his mother.

The British had gained another 15,000 square miles of empire, and so, either under direct control or through subsidiary alliances, they now possessed the whole of India. The two Anglo-Sikh Wars had been the bloodiest and most expensive the Company had ever undertaken. A handsome compensation was the acquisition of the Koh-i-Noor diamond. The massive stone was owned by Duleep Singh and was handed over in the terms of the peace treaty to the possession of Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901). There was another more valuable compensation for the costs of the wars, as, impressed by their martial abilities, the British recruited large numbers of Sikhs into their armies thereafter. After the Sepoy Mutiny of 1858 against British rule, the Sikhs were considered one of the most reliable groups to recruit soldiers from. By the First World War (1914-18), some 700,000 troops in the Indian Army came from the Punjab.