Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE, also known as Senwosret III, Sesostris III) was the 5th king of the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE). His reign is often considered the height of the Middle Kingdom which was the Golden Age in Egypt's history in so far as art, literature, architecture, science, and other cultural aspects reached an unprecedented level of refinement, the economy flourished, and military and trade expeditions filled the nation's treasury.

In Senusret III the people found the epitome of the ideal warrior-king who embodied the Egyptian cultural value of ma'at as expressed in a balanced and harmonious state and whose reign was characterized by military skill, decisive action, and efficient administration. At the head of his army, he was considered invincible; he led his troops by example and always from the front. His campaigns into Nubia expanded Egypt's boundaries, and the fortifications he built along the border fostered lucrative trade.

Although he defeated them numerous times in battle, the Nubians so respected him that he was venerated in their land as a god. He also led expeditions into Palestine and Syria and afterwards increased trade relations with those regions who respected him equally. The Egyptians conferred upon him the rare honor of deifying him while he still lived and his cult operated at the same level, and received the same recognition, as any of the great gods of Egypt.

Considering the immense honor and respect paid to him while he lived, it is little wonder that Senusret III is considered the most likely inspiration for the legendary figure of Sesostris made famous by Herodotus' account in his Histories (II.102-110). Sesostris, according to Herodotus and others, was a great Egyptian king who conquered and colonized Europe and, according to Diodorus Siculus, dominated the known world of his day. Scholars in the present day have identified this figure with a number of Egyptian kings such as Senusret I, Senusret II, Ramesses II, and Thutmose III, but Senusret III is always included in the list with distinction as the probable source of the legend.

He is also associated with the nameless pharaoh from the biblical book of Genesis, chapters 39-47, in which Joseph is sold into servitude in Egypt and wins his freedom through his ability to interpret dreams accurately. The pharaoh in these chapters elevates Joseph to a position of power second only to his own and entrusts to him the salvation of Egypt from famine.

However this association came to be made, it has no bearing on the historical Senusret III or actual Egyptian history. There is no widespread famine recorded during Senusret III's reign nor any indication he had a foreigner as vizier. Further, the motif used in the biblical narrative of seven years of plenty followed by seven lean years was common in Egyptian narratives and most likely taken from them by the Hebrew scribe who wrote the story of Joseph.

Name, Family, & Rise to Power

Senusret was the king's birth name and means 'Man of the Goddess Wosret'. Wosret was the goddess of Thebes whose name meant 'powerful', and she was honored by a number of Middle Kingdom monarchs who hailed from her city (such as Senusret I and Senusret II). Senusret III's throne name was Kha-khau-ra ('Appearing Like the Souls of Ra'). Usually a monarch put aside his birth name when he came to the throne, but Senusret departed from this tradition and ruled under his own name.

His father was the king Senusret II (c. 1897-1878 BCE) and his mother the queen Kenemet-nefer-hedjet-weret (usually given as Kenemetneferhedjet-weret and meaning 'united with the white crown-great one', a reference to the white crown of Upper Egypt). He was raised at the court of Thebes and would have been educated with his eventual succession to the throne in mind. When he was not in school, he would have engaged in athletic training with an emphasis on physical prowess and military skill.

His father, Senusret II, forged especially strong relations with the nomarchs (district governors) who were often quite powerful and had their own militias. The position of the nomarch was hereditary, initiated during the Old Kingdom of Egypt, and these governors had gained in power centuries before as the government of the Old Kingdom declined and then collapsed c. 2181 BCE. During the era known as the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 BCE) these nomarchs were more powerful than the central government and commanded the same respect previously accorded the kings of the Old Kingdom.

When the Middle Kingdom began, Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) of the 11th Dynasty defeated the kings of Herakleopolis and then punished the districts (nomes) which had remained loyal to them and resisted him. He unified Egypt with a strong central government located at Thebes. The kings who directly succeeded him maintained his policies, but Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE), who founded the 12th Dynasty, moved the capital of Egypt from Thebes to Iti-tawi in Lower Egypt, south of the old capital of Memphis, possibly in an effort to distance himself from the previous dynasty which had united the country by force and suppressed the power of the nomarchs.

Amenemhat I encouraged the nomarchs to develop their regions and allowed them significant autonomy in governing. His policies were followed by his successors and expanded upon by Senusret II. This policy allowed for significant developments in regional styles in the arts and innovations in other areas but posed a potential threat to the crown should any given nomarch become strong enough to challenge the government. By the time of Senusret II's death, the power and wealth of the nomarchs was at the same strength it had been before Mentuhotep II and rivaled the crown's. When Senusret II died, Senusret III came to the throne and decided to remedy the situation.

Social Reforms

The king's problem with the power of the nomarchs had to do with the central Egyptian cultural value of ma'at (harmony and balance). The king was supposed to maintain ma'at in a unified land, and this could not be accomplished if certain districts were powerful enough to do as they pleased if they chose to. Senusret III redistricted the country to decrease the number of nomes, and of course, this reduced the number of nomarchs.

He divided the country into three large districts – Lower Egypt, Upper Egypt and south past Elephantine (modern day Aswan), and Egyptian-held northern Nubia – and these were governed by a council, appointed by the king, who reported to the king's vizier. This policy disenfranchised most of the nomarchs but, interestingly, there is no evidence of resistance to it, nor is there any indication that the king was resented for a move which should have significantly affected the standard of living of a number of formerly powerful families. Inscriptions on the tombs of these nomarchs at Beni Hassan repeatedly give evidence that these people continued to be employed by the state and took pride in their positions and their king.

This policy resulted in a much stronger and more secure central government. The militias of the different nomes were disbanded and absorbed into the standing army of the king and the removal of the nomarchs facilitated greater wealth for the crown. Senusret III's redistricting also had the unforeseen effect of creating a segment of the population which had not existed previously: the middle class.

Prior to Senusret III's policy, Egypt was divided between the upper-class nobility and the peasantry; afterwards, with nomarchs and their extended families no longer controlling the districts, lower-level administrators found upward mobility suddenly possible and took advantage of it. More people were now working at higher-paying jobs as administrators and bureaucrats, which enriched the individual nomes and provided a greater amount of disposable income. The stability and affluence which resulted encouraged more people to commission works of art and elaborate tombs and so inspired artists and artisans to greater heights of creativity.

Art & Culture

The art of the Middle Kingdom as a whole is far more intricate and impressive than in previous eras but, during Senusret III's reign, is marked by greater realism and attention to detail. Ancient Egyptian art was functional, not simply aesthetic. The concept of 'art for art's sake' would have been unimaginable for an ancient Egyptian artist. Every work, no matter the size, was made for a specific practical purpose: statues served the spirit of the person or god depicted, temples and monuments did the same, paintings and reliefs related important historical or religious narratives, combs, boxes, jars, brushes, amulets, swords, armor, all were designed with a purpose in mind; but they still had to be aesthetically pleasing.

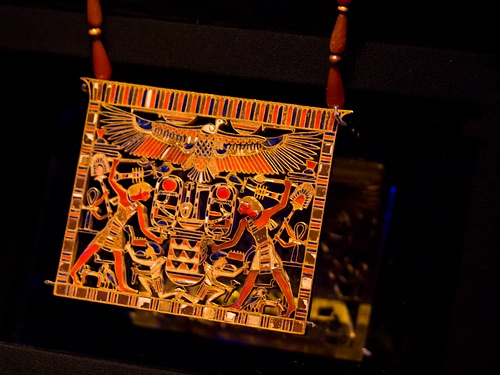

An example of this on a small scale is a pectoral (a brooch worn suspended on the chest) of Meretseger (also given as Mereret), one of Senusret III's lesser wives. The piece depicts Senusret III's victories over the Nubians and Libyans in symbolic form: Senusret III appears as a griffon destroying the enemies of Egypt while the goddess Nekhbet, in the form a vulture, hovers over his royal cartouche in the center. The pectoral is made of gold with detailed work in cornelian and lapis lazuli. On one level, it is a simple depiction of Senusret III's accomplishments, but on a more significant level, it would have served as a protective amulet, with the Nubian and Libyan figures representing threats of any kind and Senusret III-as-griffon neutralizing those threats.

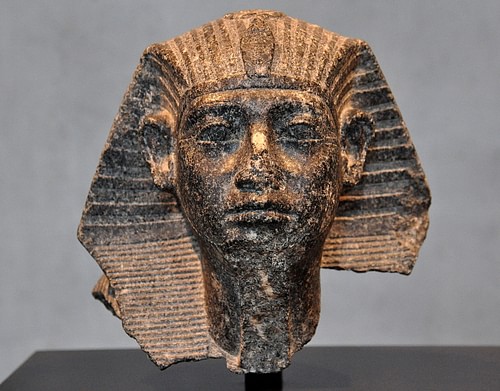

The best-known works from his reign are his own statues. Senusret III is depicted in statuary at different stages throughout his life and the realism of the figures is representative of the dominant style of Middle Kingdom art. He was a tall man, over six feet in height, always shown with a regal, somber expression. Egyptian statuary, on the whole, avoids expressive depictions because the works were made to represent the totality of the individual, not that person at any given time. Emotional states were recognized to be fleeting, and so one would not want an eternal representation of one's self smiling, frowning, jubilant, or in mourning. Senusret III's statues, however, depict the king as he would have looked at different times in his life, from his youthful confidence (the statue wears the trace of a smile) to the most famous work showing the aged king weathered by the affairs of state.

In keeping with tradition, Senusret III commissioned a number of impressive building projects. He added significantly to the growing Temple of Amun at Karnak, built an elaborate temple to the Theban war god Montu, renovated and expanded upon Abydos, and commissioned a pyramid complex at Dashur. He was also responsible for the construction of a number of forts in Nubia and along the southern border of Egypt, which regulated immigration, monitored, protected, and participated in trade, and served as supply depots for his military campaigns in that country.

Military Campaigns

Like the later pharaoh Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE), Senusret III is best known for his great military skill and succession of victories even though his accomplishments in other areas were more significant. He expanded the southern border of Egypt into Nubian territory and the north-east into Canaan through direct military engagement while the western border toward Libya was extended through negotiation. His campaign in Canaan was successful but he never seized on his victory to exploit it.

He led campaigns to Nubia in c. 1872, c. 1870, c. 1868, c. 1862, and c. 1860 BCE and was victorious in each except the last, which he aborted. Exactly why the last expedition was considered necessary is unclear, but Senusret III led his army toward Nubia when upon reaching the Nile crossing he found the water level lower than expected. His campaign relied on his ships being able to cross and return easily, and recognizing his army could be trapped in hostile territory if the Nile fell still lower, he turned them around and went home. Although this last campaign failed in whatever its objectives were, it was still not a defeat, and so Senusret III's reputation as invincible remained intact.

These Nubian expeditions are the victories which gave rise to the legend of the great conqueror Sesostris recorded in the works of Herodotus and others. Egyptologist David P. Silverman writes:

In late antiquity, Egyptian priests regaled Greek and Roman visitors with tales of the fabulous exploits of a pharaoh called "Sesostris". His conquests, they said, had ranged from deep inside Africa to the Near East and even into Scythia (southwestern Russia) which no later conqueror – not even Darius I of Persia or Alexander the Great – had been able to subdue. This image of "Sesostris" is manifestly an amalgam of several warrior-pharaohs in Egyptian history. However, he can ultimately be traced to the three Twelfth-Dynasty kings called Senwosret. (29)

Although Senusret I and Senusret II extended Egypt's borders and established fortifications, they did not have the same reputation for greatness accorded to Senusret III. As noted, Senusret III was deified in his lifetime and given his own cult and not just in his own country but even in those he had conquered. Although Senusret I and Senusret II engaged in Nubian campaigns, they never extended the border as far as Senusret III; this makes him the most likely historical basis for Sesostris.

His primary focus throughout his reign was on the south, and his victory stele at Semna (in Nubia) claims: "I have made my boundary further south than my fathers. I have added to what was bequeathed to me. I am a king who speaks and acts. What my heart plans is done with my arm" (Lewis, 87). His four campaigns against Nubia opened up the rich gold mines to Egypt, which contributed to the prestige of Egypt in foreign trade and commerce.

With the southern border secure, Senusret III commissioned a canal enlarged at Sehel to facilitate trade between Nubia and Egypt, which allowed merchants traveling by water to avoid the perils of the Nile rapids at the First Cataract. The canal, as well as the forts strung along the border and throughout northern Nubia, allowed for a mutually beneficial trade arrangement between the two countries, which also naturally resulted in cultural diffusion.

Conclusion

Nubians served in the Egyptian army as mercenaries, as the core of the Egyptian police force, and as guards for royal and non-royal trade expeditions. Although in official Egyptian inscriptions the Nubians, like all non-Egyptians, are regularly depicted in negative terms, in reality they were an integral aspect of Egyptian life and admired the Egyptian culture.

The clearest evidence for this is the veneration of the god Amun in Nubia and the construction of temples and buildings modeled on Egyptian architecture. The Cult of Amun in Egypt was the most powerful and wealthy throughout the country's history. From the Old Kingdom onwards, Egyptian kings struggled with this particular cult which, at times, was more powerful than the crown. One of the most interesting aspects of Senusret III's reign is his patronage of the Amun cult. Instead of tolerating or resisting their influence, he worked with them and supported their efforts at Thebes.

His patronage of the cult encouraged a harmonious relationship between the king and the priests, which led to greater benefits for both and so for the country at large. Further, the Nubian respect for Senusret III naturally led to a greater veneration for his god, which resulted in religious harmony between the two countries.

Although there were many great kings throughout Egypt's history who honored and adhered to the concept of ma'at, few exemplified that principle of divine balance as closely as Senusret III. Pharaohs of the New Kingdom of Egypt would emulate his reign, and centuries after his death he was still prayed to and worshiped as a divine representative of the best gifts the gods gave to the Egyptian people.