The 1857-8 Sepoy Mutiny (aka Sepoy Rebellion, Indian Mutiny, The Uprising or First Indian War of Independence) was a failed rebellion against the rule of the British East India Company (EIC) in India. Initially a mutiny of the Indian soldiers (sepoys) in the EIC army, the movement spread to become a wider rebellion involving a broad spectrum of the Indian population in certain regions.

The rebellion was ultimately quashed, but the victor was also its immediate victim as the British state dissolved the EIC and took over governance of its possessions in India. The grievances that caused the rebellion and the acts of violence perpetrated by both sides would colour Anglo-Indian relations for the next century and beyond.

Naming the Mutiny

The very name of the traumatic events of 1857-8 has changed over time as colonial historians have moved aside for more neutral ones, who have in turn been challenged by writers with a nationalist agenda, and this on both sides. That the events involved far more than merely disaffected soldiers of the EIC and so drifted from a mutiny to a wider rebellion is clear. A significant part of India's population in key areas was directly involved, and in this sense, it was a true popular rebellion or uprising. On the other hand, many Indians remained loyal to the status quo or, as was the case with several princely states, they remained neutral.

Most historians agree that the events of 1857-8 can not be described as a truly "national movement for independence" for the very good reason there was no single Indian nation at that time. Neither was there any real coordination between the various groups of protestors who all had different aims, even if many can be broadly described as being anti-colonial. On the other hand, the people involved did come from all walks of life, and so, in this sense, the uprising did have a 'national' character. If anything, the debate over what exactly to call the events of 1857-8 is indicative of the complex tensions in India both before, during, and long after they had subsided. As the historian I. Barrow summarises: "What the rebellion was (and what it subsequently meant) is one of the great debates of South Asian and British imperial history" (116).

Sepoys in the EIC Army

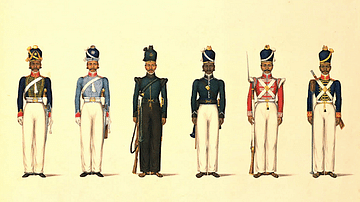

Although the East India Company was established as a trading company, from the mid-18th century, it employed its own army to protect its interests and to expand its territorial possessions. From 1765, only Britishers could hold officer rank in the EIC armed forces, but the rank-and-file majority was made up of Indian soldiers. These latter troops were first known as peons and then sepoys – a corruption of the Persian term sipahi. Sepoys far outnumbered European soldiers. The average ratio of Indian troops to British in EIC armies in the 19th century was around 7:1. Many Indians joined the EIC for better pay than was possible elsewhere and as a chance to improve their status in traditional Indian society. Dependency on such a large number of Indian soldiers was a risk for the Company, but one it had to take given the difficulties in recruiting British soldiers and enticing men of experience to defect from the regular British Army. The sepoys were well-trained and well-equipped, and they helped the EIC expand its control across India, especially following the four Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799) and the two Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845-1849). At the time of the Sepoy Mutiny, the EIC employed around 45,000 British soldiers and over 230,000 sepoys.

Causes of the Rebellion

The main causes of the Sepoy Mutiny may be summarised as:

- Sepoys were unhappy with the pay inequality compared to British soldiers.

- Sepoys were suspicious that rifle cartridges used animal fats they could not touch as part of their religious beliefs.

- The sepoys' unwillingness to serve abroad.

- Indian princes had lost their states or had to pay high protection fees to the EIC.

- An overtaxed population

- Concerns that traditional Indian cultural practices were under threat.

- Concerns for traditional Indian manufacturing industries facing unfair competition from EIC imports.

- British snobbery and institutional racism.

The sepoys had several grievances, which they felt, despite peaceful protest, were not being addressed by the EIC. There had been several small-scale uprisings since 1806, but these had been ruthlessly quashed. The sepoys were not happy that they received much lower pay compared to British EIC soldiers. Neither had sepoy wages been raised for over 50 years, meaning that in real terms their pay had lost half of its value since 1800. Indian soldiers were not happy either with the obligation to serve outside India, which would require Hindus to perform costly rites of purification, or the institutional racism that prevented them from ever becoming officers. The final straw was the introduction of greased cartridges for compulsory Enfield rifles. The animal fat grease of pig or cow offended Hindu and Muslim beliefs since the cartridges had to be prepared by mouth (as it happened the grease came from neither of these taboo animals). The cartridge rumour fueled others, such as that sepoy flour was being mixed with cow and pig bones or that their salt was being deliberately contaminated with pig and cow's blood (the salt did have a red tinge, but this came from the sacking used to transport it). In short, the segregation of men from officers and a lack of communication between the two groups was building a powder keg of mutual suspicion.

There were other discontents besides the sepoys. 1857 saw the collapse of the Mughal Empire, which had been crumbling for quite some time, its institutions of rule in India now all but invisible. Many of the independent Indian princely states were far from happy with the EIC, in many places the Mughals' successor. Some princes had benefitted from hiring out EIC armies to quash their own interior rebellions and to defeat their neighbours, but others were obliged to pay the EIC 'protection money' in a system not far removed from extortion.

Another serious bone of contention was the EIC's policy of taking over princely states whenever it could get away with it. Indian princes not being allowed to pass on their territories to an adopted son when they had no direct heir – the Doctrine of Lapse – was one method of acquisition, particularly after 1848 when the Marquess of Dalhousie (1812-1860) became EIC Governor-General. Even accusations of poor governance led to some princes losing their throne. The aggressive expansionist policies of the EIC led to several princely states actively joining the Sepoy Mutiny and others remaining neutral.

The ordinary people of princely states also suffered. Ever since the 1793 Bengal Permanent Settlement, the EIC had been rapaciously extracting taxes from the peoples it governed, even in times of crisis. Indians were not happy with the British justice system and police that imposed these fiscal obligations. With the removal of some princes, a whole network of employment was lost, especially for soldiers and armourers. Artisans suffered from competition from EIC-imported goods, particularly textiles made in the great northern manufacturing mills of England, and the EIC had a stranglehold on the indigo and opium business through its trade monopoly.

Lord William Bentinck (1774-1839), Governor-General of the EIC from 1828, was known for his social reforms and most notoriously for his abolition of sati (aka suttee) in 1829. Sati is the custom for a Hindu widow to sacrifice herself on the funeral pyre of their late husband. There may have been those glad to see the end of this ritual, but there were others equally concerned that other cultural practices might be next in what was considered the EIC's continued 'Westernization' of India. Educating Indians in English and preparing them for a servile life in the lower ranks of the British administration was advocated by such figures as Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859), a member of the EIC Council, who famously denigrated the value of Indian classical education. Missionaries were permitted by the EIC into India from 1833, and their presence was another assault on Indian culture. The institutional racism of the EIC and the snobbery of the British were additional, not insignificant causes of discontent.

The Rebellion Spreads

The initial spark that set off the sepoys was the punishment of one of their own, Mangal Pandey (aka Pande), in March 1857. Pandey had wounded a European EIC officer near Calcutta, and for his crime, he was executed. This was a matter of justice perhaps, but the outrage sprang from the decision to also flog Pandey's entire sepoy company. Then, on 10 May 1857, the EIC sepoys at Meerut raised arms. They protested the 10-year prison sentences handed down to 85 fellow sepoys for refusing to use greased Enfield cartridges. The mutineers killed their British officers and then went on a rampage. As one mutineer lamented: "I was a good sepoy, and would have gone anywhere for the service, but I could not forsake my religion" (James, 239). The mutineers captured nearby Delhi on 11 May, murdering European men, women, and children as well as Indians who had converted to Christianity.

The EIC leadership was unprepared for the rising, which saw the sepoys promote the retired Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah II (1775-1862) as their leader. Then the rebellion spontaneously spread across India, involving not just sepoys but landlords, merchants, and peasant farmers of both the Hindu and Muslim faiths. Bengal was where the EIC had real problems. 45 of the 74 sepoy regiments in the Bengal army rebelled. As a precaution, 24 of the remaining 29 sepoy regiments were disbanded or disarmed by the EIC. The Bengal cavalry regiments also mutinied. Fortunately for the British, in the EIC's other two main centres – Madras and Bombay (Mumbai) – the former army remained loyal, and only two regiments rebelled in the latter.

The sepoy cause was then taken up by a host of Indian princes disgruntled at their poor treatment by the EIC. Queen Rani Lakshmi Bai of Jhansi (1835-1858) and Nana Saheb, claimant to the Maratha title of Peshwa, were examples of rulers who raised arms against the EIC. Some princes remained loyal to the EIC such as the Maharajas of Gwalior and Jodhpur (although some of their troops nevertheless mutinied). At the same time, the violence and widespread looting and extortion convinced many better-off Indians to remain in support of the EIC's rule rather than see their businesses fold and towns descend into total chaos. There were also those who tried to remain neutral when they could.

The rebellion continued to spread with remarkable speed, helped by agents sent out for that very purpose and new people joining it after they witnessed the rebels' success and the weakness of the British. In many cases, too, the rebels had nothing to lose. Most of northern and central India was literally up in arms, particularly in the Ganges and Narmada valleys. As the EIC mobilised loyal troops, fierce fighting broke out at Banaras, Gwalior, Jhansi, Kampur, and Lucknow. There were lesser episodes of rebellion in Assam, Rajasthan, and Punjab. To fight the rebels, the EIC now employed the regular British Army regiments, which it typically hired out, along with loyal Sikh troops and new allies such as the Gurkhas from Nepal. Delhi was retaken on 18 September 1857 after a brutal six-day battle, then Kanpur and Lucknow in March 1858.

The rebellions were ultimately quashed by the spring of 1858 for two reasons: the far superior resources of the EIC and the lack of coordination amongst the rebels in terms of command and demands. Particular groups, although not split along religious lines, each had their own grievances they wanted addressed, ranging from grand schemes like reinstating the Mughal emperor to petty acts of vengeance against a hated local tax collector. These different groups might have all agreed that they wanted the British out of India, but they could not agree on who would replace them. In the end, 40,000 British troops shipped in from Europe decided the conflict in the EIC's favour. In June 1858, Lord Canning, Governor-General of the EIC, announced that peace had been restored and that Queen Victoria promised amnesty for the rebels, a guarantee of the rights of Indian princes, and religious toleration for all.

Aftermath

Casualties were high on both sides, but far more so on the Indian side, as here summarised by Barrow:

2,600 British enlisted soldiers and 157 officers were killed. Another 8,000 died of heatstroke and disease, while 3,000 were severely injured. Indian deaths from the war and the resulting famines may have reached 800,000.

(115)

Atrocities and massacres were committed on both sides against military personnel and civilians in cities and rural areas. There are countless documented cases of unlawful imprisonment, torture, rape, execution without trial, and murder against European and Indian men, women, and children, and people of all religions. This bloodbath understandably led to much ill feeling and mutual suspicion over the next century.

In the aftermath, the EIC ruthlessly dealt with the rebellion's leaders. Bahadur Shah II was exiled to Burma, but his sons were executed. Queen Rani Lakshmi Bai was killed in battle, and another prominent rebel leader, the Maratha Tantia Tope was executed. The British, for reasons unbeknown but to themselves, blamed Muslims for the rebellion far more than Hindus, and British soldiers were often guilty of harsh treatment or worse of captives of the former religion. There were so many lootings, kangaroo courts, and hangings that even the EIC directors had to issue a resolution to its employees to show more restraint. The historian W. Dalrymple describes the thousands of revenge hangings and murders as "probably the bloodiest episode in the entire history of British colonialism" (391).

The British state, already unimpressed with the EIC's governance in India, took the final step in what had been a gradual process of regulation and control to finally take full possession of EIC territories in India on 2 August 1858. As far as Parliament was concerned, the EIC had neither the right nor the competence to wage wars in the name of the British people. The Sepoy Mutiny was taken as a warning that a commercial company with nobody to answer to but its shareholders could not and would not rule people through consent, compromise, or suitable attention to justice.

The EIC navy was disbanded, and in June 1862, the EIC's nine European regiments were taken over, although it was not until 1895 that the various surviving EIC presidency armies were finally united into a single British Indian Army. This new army had a much higher proportion of British soldiers than its predecessor.

The Mutiny did not lead the British to question what they considered their right to colonise India, it made them search for the errors they thought they had made in their colonial rule. So began what is popularly termed the British Raj (rule). On 1 June 1874, Parliament formally dissolved the East India Company. The sepoys and the Indian civilians who had joined them had seen off one oppressor only for it to be replaced by another, or rather the same but with a different mask. In 1877, Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India, and British rule continued to squeeze what resources it could from India until independence was gained in 1947, a movement that drew much inspiration from the mutiny almost a century before.