Serket (also known as Serqet, Selkis, and Selket) is an Egyptian goddess of protection associated with the scorpion. She was worshipped widely in Lower Egypt as a great Mother Goddess in the Predynastic Period (c. 6000- c. 3150 BCE) and so is among the older deities of Egypt.

She is associated with healing, magic, and protection, and her name means "She Who Causes the Throat to Breathe". Her symbols are the scorpion, the Ankh, and the Was Sceptre, all of which convey her benevolent aspects. In the Predynastic Period, she was the protector of the Kings as evidenced by archaeological finds linking her by the name Serqet to the Scorpion Kings, defeated at some point around the reign of Narmer (r. c. 3150 BCE). During that period she was already closely associated with protection and her worship had grown from the Delta Region of Lower Egypt to the cities of Upper Egypt.

By the time of the First Dynasty (c. 3150-2890 BCE) she was associated with the god Nun (also known as Nu), the Father of the Gods. Nun was the watery abyss from which the primordial hill (the ben-ben) rose on which Atum (Ra) stood at the dawn of creation. It is unclear what role she played, if any, in the creation of the world, but evidence suggests she may have been the wife of Atum, the first son of Nun, or even the wife of Nun himself. Later, she is represented as one of the deities aboard the barge of the sun god Ra, who watch out for the serpent Apophis as the boat sails through the night sky.

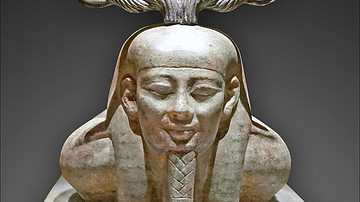

She is the goddess of venomous creatures, most notably the scorpion, and is depicted as a beautiful woman, arms outstretched in a gesture of protection, with a scorpion on her head. The scorpion is purposefully shown without a stinger or claws to represent Serket's role as protector against venomous stings. Serket was eventually absorbed into the Cult of Horus where she became closely associated with death and the souls of the deceased. She was then known as "Lady of the Beautiful Tent" which referred to the tent of the embalmers. She is best known for her golden statue and the alabaster canopic jar from the Tomb of Tutankhamun.

Early Role in Religion

There are no mythological tales extant of Serket's origin as there are for most of the other Egyptian gods. She is referenced as being present at the creation of the world but no mention is made of her role. She was seen as a mother goddess in the prehistoric period of Egypt and was already associated with the scorpion which "was a symbol of motherhood in many areas of the Near East" (Wilkinson, 234). She is depicted as nursing the kings of Egypt in the Pyramid Texts, which date to the Old Kingdom (2613-2181 BCE), and one of the protective spells from those texts - known as PT 1375 - reads, "My mother is Isis, my nurse is Nephthys...Neith is behind me, and Serket is before me" (Wilkingson, 233). These four goddesses would later be represented famously in Tutankhamun's tomb on the canopic chest and as gold statues protecting the gilded shrine.

There is no evidence of temples to Serket in any region of Egypt suggesting to some scholars that she either never had any or, more likely, that she was absorbed into the figures of other deities such as Hathor or Neith, who are equally ancient. Neith was the patron goddess of the Delta city of Zau (later known as Sais). Like Hathor, Neith was originally a fierce goddess associated with destruction who later came to be related to weaving and then to wisdom (just as Hathor was originally a blood-thirsty destroyer who became a benevolent protectress). It is possible that Serket followed this same pattern first arising as a mother goddess with a slightly swollen womb and then coming to be associated with scorpions and venom because scorpion bites were so often fatal to Egyptian children. Scholar Geraldine Pinch writes:

Scorpion stings were a common hazard in Ancient Egypt. The female scorpion is larger than the male and has a greater supply of poison. Representations of Selket always show the tail raised in the stinging position. Scorpion stings cause a burning pain and shortness of breath and can be fatal to young children and the elderly. (189)

Her name, "She Who Causes the Throat to Breathe" comes directly from her association with the scorpion. Amulets were carried with her name on them to protect people from scorpion bites or to help them breathe if they were bitten.

Serket & the Osiris Myth

The Osiris Myth was the most popular story in ancient Egypt, gaining adherents steadily until, by the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE), it significantly informed the values of Egyptian culture. The Osiris Myth tells the story of the god Osiris and his sister-wife Isis who reign over the early paradise of the world. Their brother Set becomes jealous of Osiris and traps him in an ornate casket, killing him, and then hurls the box into the Nile.

Isis retrieves her husband's body and brings him back to Egypt, hiding him in the swamps of the Delta region. She asks her sister Nephthys to stand guard while she goes to gather herbs to return him to life but, while she is gone, Set finds Nephthys and tricks her into revealing where Osiris' body is hidden. He hacks the body to pieces and scatters them across Egypt and into the Nile, and when Isis returns, she only finds the weeping Nephthys who tells her what has happened.

Isis and Nephthys seek out and find all the body parts, and Isis is able to revive her husband. His penis has been eaten by a fish, however, and so he is incomplete and cannot remain as lord on the earth. Prior to his descent to the underworld, Isis turns herself into a falcon and flies around his body, gathering his seed into her own, and becomes pregnant with a son, Horus. Osiris then leaves to assume his new role as Judge of the Dead and Isis is left alone to hide herself and her newborn son from Set.

Serket is sometimes included in the story at this point in her role as protector of the innocent. Isis has a difficult labor and gives birth to Horus in the swamps of the Delta. Serket presides over the birth keeping venomous scorpions and snakes away from the new mother and child. This part of the story would later be cited in Serket's role as protector of women in childbirth and of mothers and children. After Horus' birth, Isis had to continue to hide in the marshes from Set and only went out at night for food. At these times, Serket guarded the baby and sent her scorpions with Isis as her bodyguard.

Serket & the Seven Scorpions

One of the most popular stories concerning Isis is known as Isis and the Seven Scorpions. It relates how, when Horus was an infant and Isis was hiding him in the swamp lands, Serket had seven scorpions keep her company. When Isis went out to beg for food in the nearby towns, three of them - Petet, Tjetet, and Matet - would go before her to make sure the way was safe and Set was not waiting in ambush, two were on either side of her - Mesetet and Mesetetef - and two brought up the rear - Tefen and Befen, who were the most fierce - in case Set chose to attack from behind.

Whenever she left the swamp, Isis would conceal her glory so she looked like a poor, older woman asking for alms. One night, as she and her bodyguard entered the town, a very rich noblewoman looked down on them from her window and quickly slammed her door and locked it. Serket, though watching over Horus in the swamp, could see all that her scorpions saw, and she was angered at this affront to Isis. She decided the woman would pay for the insult and sent a message to Tefen that he should take care of the situation. The other six scorpions all surrendered their poison to Tefen who drew it up into his stinger and waited for the right moment. In the meantime, a poor peasant woman had seen the noblewoman refuse hospitality and, even though she had little, offered Isis and her scorpions a place under her roof for the night and a simple meal.

While Isis was eating with the young woman, Tefen snuck out of the house and crept beneath the door of the home of the noblewoman, where he stung her young son. The boy fell down in a stupor, and the noblewoman grabbed him up and tried to revive him but could not. She ran into the streets, crying for help, and Isis heard her. Even though the woman had refused her food and a place for the night, Isis forgave her. She did not want the boy to pay for his mother's insult. Isis took the child in her arms and called each of the scorpions by their secret name, thereby dominating them and neutralizing their power, and recited spells of great magic. The poison evaporated, leaving the child's body, and he revived. The noblewoman was so grateful and so ashamed of her earlier behavior, she offered all her wealth to Isis and the peasant woman. Serket, back in the swamp with Horus, regretted having sent the scorpion to attack the innocent boy and vowed to protect all children in the future.

Transformation of Serket

In the same way that the Osiris Myth changed the god Set from a protector hero-god into a villain, it changed Serket's role. Although she continued to be seen as a protectress, her earlier attributes as mother goddess were assumed by Isis while Serket became associated with death and the afterlife. In the story of the seven scorpions, Serket is often omitted entirely, and the focus of the story is on the forgiveness of Isis and the proper way people should treat each other. After the Osiris Myth had taken precedence in Egypt, Serket's role was marginalized on the earthly plane but amplified in the afterlife.

Serket became known as one of the guardian gods who stand watch over souls in the afterlife. Specifically, as Geraldine Pinch notes, she "is one of the deities who guards a bend in the river on the watery route to paradise" (189). She was invoked at funerals for her magical abilities as it was thought she could help the dead to breathe again as they were reborn from their bodies in the afterlife.

In the same way that she rewarded the justified dead with breath, she punished those who were unworthy with breathlessness. The Egyptian afterlife is depicted in a number of different ways with the most popular involving Osiris as Judge of the Dead in the Hall of Truth. If the heart of the deceased weighed more than the feather of ma'at in the scales, it was dropped on the floor and devoured by the monster Ammut; then the soul would cease to exist. In another version, however, the souls of the unjustified are punished for their misdeeds by the Forty-Two Judges who preside with Osiris and Thoth over the Hall of Truth. These souls could be turned over to deities like Serket who would unleash their wrath and torment those who had abused the gift of life.

Similarly, those on earth who preyed on the innocent or engaged in wickedness might be visited by Serket and her scorpions, who might only scare them with a mild bite, bringing shortness of breath and pain, or a stronger dose of venom leading to death. In her role as a goddess of death and the afterlife, she was also responsible for guarding the internal organs of the dead king as it was thought he would need them again once he was reborn after death. She was the protector-goddess of one of the Four Sons of Horus, Qebhesenuef, who guarded the intestines in the canopic jar. Serket was the goddess of poisons and the Egyptians associated the intestines with poison, thus she was given charge over the safety and well-being of Qebhesenuef.

Worship & Clergy

The most significant way in which the Osiris Myth transformed Serket was to attribute her earlier manifestations of power to Isis. She remained a very popular goddess, however, and should not be considered a "lesser goddess" as so many writers on Egyptian mythology refer to her. Although she did not have official temples in her honor, her priests and priestesses were highly sought after and valued greatly for one simple reason: they were doctors.

The clergy of the Cult of Serket were all physicians known as Followers of Serket. Men and women could practice medicine and perform the Rites of Serket. According to historian Margaret Bunson, the practice of medicine was "the science conducted by the priests of the Per-Ankh, the House of Life. The Egyptians termed it the "necessary art" (158)". The House of Life was not a physical location, though it could be, but was a concept of healing. The priests and priestesses of Serket carried the House of Life within them in their knowledge of how to heal. Bunson writes:

Diagnostic procedures for injuries and diseases were common and extensive in Egyptian medical practice. The physicians consulted texts and made their own observations. Each physician listed the symptoms evident in a patient and then decided whether he had the skill to treat the condition. If a priest determined that a cure was possible, he reconsidered the remedies or therapeutic regimens available and proceeeded accordingly. This required, naturally, a remarkable awareness of the functions of the human body. The physicians understood that the pulse was the "speaker of the heart" and they interpreted the condition now known as angina. They were also aware of the relationship between the nervous system and voluntary movements. (158)

Not every physician in Egypt was a Follower of Serket but a good many were. Serket, as goddess of healing and protector against poison and venomous stings, was naturally the patron of doctors, even those who were not directly involved in her cult. Spells invoking Serket for healing were widely used throughout Egypt. The scholar John F. Nunn notes this, writing:

The recto of the Chester Beatty papyrus VII, written in the reign of Ramesses II, contains a number of magical spells for protection against scorpions. Most invoke various wives of Horus whom Gardiner [the Egyptologist, in 1935] suggested might be merely appelations of Serqet who is actually named in the eighth spell:

"Someone approaches me."

"It is not I who approach you, it is Wepet-sepu, wife of Horus, who approaches you."

"You poisons, come forth to me. I am Serqet." (101)

In this spell, the physician would recite the lines as though the patient were having a dialogue with the goddess or goddesses. When 'Serket' said her final line, the poisons were supposed to leave the body of the sick person. Although she is not mentioned by name in every papyrus or inscription, her powers of healing would have been invoked no matter which aspect she was named as or what other goddesses were called upon. In her role as patron of physicians and healing goddess, she helped the people of Egypt from their birth, through their lives, and even into the afterlife.