Ship Money was a tax applied by medieval monarchs to English coastal communities to pay for ships for the Royal Navy and so ward off pirates and enemies of the state. During the reign of Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649), the tax was used for other purposes and applied to other, inland communities.

Into the 17th century, the Ship Money levy was unpopular but highly successful in enriching the monarch's coffers. It effectively had become a land tax which King Charles could raise without the consent of Parliament, and so it became a legal and constitutional issue between Royalists and Parliamentarians. In this sense, the levy was one of the many causes of the English Civil Wars (1642-1651), even if it was abolished in 1641 before arms were raised.

Origins

The origins of Ship Money go back to the medieval period, where it was a form of feudal service, just as noblemen had to provide a certain number of medieval knights for the royal army, so some coastal communities were asked to provide ships. As piracy was a perennial problem, it was considered a benefit of the tax that the resulting ships could be used to clear coastal waters of this menace to all. In practice, then, whenever a monarch needed a navy – for defence or an expedition to Continental Europe – key port towns were obliged to donate ships since there was, at this time, no permanent navy. Merchants might also lease ships to the Crown. If the ports had no ships to give, or an insufficient number, then they could, instead, give a sum of money to the Crown, which was then used to build more. This money was called Ship Money.

Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509) was the first English monarch to create a drydock for the express purpose of building and maintaining a permanent navy, or at least the nucleus of one. Plymouth, on the southern coast, was the location of this drydock, the first in northern Europe. Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547) was the first monarch to maintain a permanent navy of any size, around 50 ships. The reign of Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) then saw some significant challenges, like the Spanish Armada in 1588, which required an expansion of investment in the navy and England's naval facilities (a second base was built at Woolwich, for example). More ships were needed for the raid on Cadiz in 1596. Elizabeth also loaned out royal ships to her privateers who sailed them around the world on their treasure-hunting trips. All of these activities required cash, of course, and the Ship Money tax was one means to provide it. To get more returns, Elizabeth insisted not only that ports provide ships and cash but also the counties in which these ports were located should contribute. This was not a popular move with rural communities, and many refused to pay, but the situation of the war with Spain meant the queen could do little to impose the tax and so risk the goodwill of her subjects. For this reason, Ship Money was not a great source of revenue in this period.

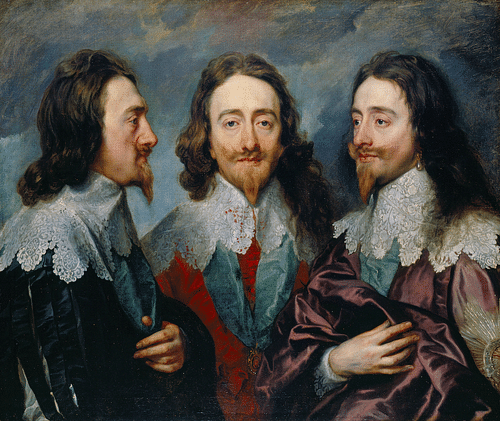

Misuse by Charles I

Charles I, the second Stuart king after his father James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE), broke the convention that had been established during the Tudors that a monarch called a parliament when it wanted to raise finances, for example, to fund a war or a large building project. The MPs would then decide on a budget and how to raise the money, usually through various taxes and duties. Parliament had raised various objections to Charles' approach to government in such documents as the Petition of Right of 1628, and so the king decided to do without it.

As part of his strategy to raise taxes and duties outside of Parliament, Charles issued a writ and applied the Ship Money levy in 1627. Encouraged by its success, he widened the application of Ship Money during that period of his reign known as the 'Personal Rule' when no parliaments were called (1629-1640). From October 1634, Ship Money was again levied and then applied to all English and Welsh counties. The money was to be provided by a county or town on a quota system. The local authorities, headed by the county sheriff, then extracted the tax based on a person's earned income and their income from land (although a ship or service could still be offered instead). People were given five months to pay up to the local justices made responsible for its collection. Unlike in previous periods when the tax was applied when specific naval needs developed, Charles applied the Ship Money levy every year. The king also pointed out that the whole kingdom benefitted from having a powerful naval force, not just the coastal communities.

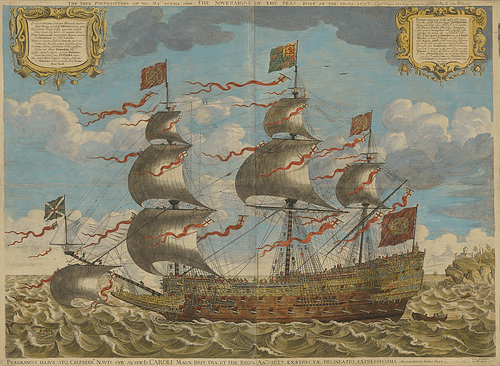

The tax was, like any other, unpopular, but for the king, at least, it was successful in that he did indeed gather significant new funds. The Crown received well over 90% of the Ship Money levies it applied in the mid-1630s, a very high success for any tax, especially in peacetime. In each of the years 1635, 1636, and 1637, Ship Money raised nearly £200,000 ($65 million or £48 million today). This figure was around one-third to one-quarter of the king's total annual income, depending on the year. Charles did use some of the Ship Money on its intended purpose: ships. The king had a fleet of 25, and one of the finest was The Sovereign of the Seas, built at a cost of £65,000 (although its great gilded stern was an unnecessary extravagance).

The Hampden Case

Some tried to avoid paying the levy, but they were usually imprisoned and brought before the courts. John Hampden was at the centre of a very particular case involving Ship Money in 1637. Hampden, an immensely rich Puritan from Buckinghamshire, not only refused to pay the tax but also wished to contest in court the very lawfulness of its application. Hampden's case rested on the tradition that only Parliament could raise taxes, and since Charles had not called one for so many years, the reinstatement of Ship Money could not be considered legal. Neither was England then at war and so it was difficult to say the nation was facing a national emergency. Charles' lawyers countered with the argument that the construction of ships took many months and so funds had to be acquired long before a war broke out. Further, naval ships were needed at all times to protect merchant shipping from pirates and the fleets of enemy states.

Perhaps pressured by the king, the Court of Exchequer ruled in his favour. It was a close call as seven judges voted for the king, with five against (although three of the latter group had spotted a legal technicality that had weakened the king's case). It may be that the judges could not bring themselves to establish a legal precedent and/or question the divine right of their king to decide what is and what is not lawful.

A court decision in 1636 had already ruled that Charles could raise taxes in a national emergency, and so this and the Hampden case together did now seem to give the monarch the green light to raise any taxes he wished for whatever purpose. As one judge had summarised, "The law is, of itself, an old and trusty servant of the King's; it is his instrument or means by which he useth to govern his people by…" (Anderson, 56). There remained the limitation that the king must state there was actually an emergency, but such an ill-defined term could easily be applied to any number of situations the king wished. Further, to question that any given situation was not an emergency was to doubt the king's integrity, an offence that bordered on treason.

In practice, the king had moved far beyond these legal technicalities and was now using the tax not only for the navy but also to pay his land army to meet incursions from the Scots. Nevertheless, the legal and constitutional question remained: what was the relationship of power between monarch and Parliament when it came to finances? Charles was adamant he had every right to impose whatever taxes he required, and he even persuaded such Church figures as William Laud (1573-1645), the Archbishop of Canterbury, to come out and speak in favour of the king's right. The royal finances and Ship Money, in particular, would very soon be one of the issues on which hinged the future of the monarchy in England.

Abolition

Despite the legal and religious backing, both political and actual resistance to the Ship Money tax grew significantly as the decade drew to a close, fuelled, undoubtedly, by the very public proceedings and consequent public interest in the Hampden case. There were even some county sheriffs refusing to levy the tax in their jurisdiction. This led to Charles reducing the demand from £200,000 to just £70,000 in 1638, but even this low figure was not met. The presentation to Parliament at the end of 1640 of the Root and Branch petition outlined 28 grievances with the king's rule, and one of these was the application of Ship Money. The almost contemporary Petition of Twelve Peers also called for the tax's abolition. For many, Ship Money had become a byword for all unpopular and illegal taxes.

By 1639, when the king needed Parliament to convene again to raise funds for his armies to better deal with the series of Scottish invasions, MPs took the opportunity to insist that Ship Money be abandoned. Consequently, the Long Parliament made Ship Money illegal in August 1641. In addition, the decision of the court in the Hampden Case was formally reversed. Unfortunately for many communities, during the long and bitter English Civil Wars that now began, they ended up paying even more taxes than they had ever paid under the Ship Money scheme.