The Silla kingdom ruled south-eastern Korea during the Three Kingdoms period from the 1st century BCE to 7th century CE. The capital was Geumseong (Gyeongju) with a centralised government and hierarchical system of social ranks. The prosperity of Silla is evident in the magnificent gold crowns which are among the most prized art objects of ancient South-East Asia.

The Silla were in constant rivalry with their neighbours the Baekje (Paekche) and Goguryeo (Koguryo) kingdoms, as well as the contemporary Gaya (Kaya) confederation. An alliance with the Tang Dynasty of China permitted Silla to eventually conquer the whole of the Korean peninsula in 668 CE, which it then ruled for the next three centuries as the Unified Silla Kingdom.

Historical Overview

The traditional founding date of the Silla kingdom (often Ko-Silla - 'Old Silla' - to distinguish it from the later unified period) was, according to the 12th-century CE Samguk sagi ('Historical Records of the Three States'), 57 BCE, but this is unlikely to be accurate and modern historians prefer a later date when describing the Silla as a single political entity. The kingdom first developed when Jinhan tribes in south-eastern Korea formed a confederacy. The traditional founder figure is Hyeokgeose (r. 57 BCE – 4 CE) who, once he was born from a magical scarlet egg, founded his fortified capital at Saro, later to become known as Geumseong (modern Gyeongju/Kyongju).

The first leaders carried the title chachaung, meaning shaman or priest, suggesting they were selected because of their role as community shamans. The dominant clans in this early period were the Pak, Sok, and Kim. Nulchi (r. 417-458 CE) established a father-to-son inheritance of the crown, replacing the previous rotation system between the clans. During the reign of king Soji (458-500 CE) post stations were established to better link the various fortified cities of the group. The capital, Saro, gave the kingdom its first name (also known as Seorabol meaning 'Eastern Land') which was changed to Silla during the reign of king Beopheung (r. 514-540 CE) when a greater degree of centralisation was achieved.

Silla battled constantly over the centuries with the neighbouring kingdoms of Goguryeo, Baekje, and the Gaya confederation, with all four vying for greater control of the Korean peninsula and constantly switching allies. The Silla kingdom did have the advantage of protection from local mountains which isolated it to some degree from the other Korean states. Silla formed an alliance with Goguryeo to rebuff a Japanese-Baekje army in 400 CE, but when Goguryeo became more territorially ambitious in the 5th century, Baekje and Silla formed a long-lasting partnership between 433 and 553 CE.

Silla prospered in the 6th century during the reign of Jijeung (500-514 CE) with greater agricultural yields coming from the introduction of oxen-drawn ploughs and irrigation systems. The kingdom also benefitted from natural resources such as iron and gold. Silla-manufactured goods included silks, leather products, furniture, ceramics, and metal tools and weapons, all of which were supervised by dedicated government departments.

Relations with Baekje turned sour when Silla occupied parts of the lower Han river valley. In 554 CE, at the battle of Gwansan (modern Okcheon), Silla defeated a Baekje army and killed their king Song. This move gave Silla access to the western coast and the Yellow Sea, providing the possibility to forge greater links with China.

More success came in the south with the Silla attack on the Gaya ruling city-state Geumgwan Gaya (Bon-Gaya), which fell in 532 CE. By 562 CE Daegaya also fell and the Gaya confederation was wholly absorbed into the Silla kingdom. This still left two dangerous opponents in Goguryeo and Baekje, and they combined effectively to conquer Daeya-dong (modern Hapcheon), also in 562 CE. Silla would require outside help to realise its ambition of controlling all of the peninsula.

Fortunately for the Korean kingdom, China was now ruled by the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) who saw an opportunity to play these troublesome southern kingdoms against each other for their own benefit. Selecting Silla as their ally, things did not at first go well when a joint Silla-Tang army was defeated by a Goguryeo army led by the celebrated general Yang Manchun in 644 CE. Three more times Tang armies were defeated over the following decade. Then, in a few action-packed years, the whole political map changed dramatically.

A massive joint Tang and Silla army and naval force was formed for one big and decisive push. The Silla army of 50,000 was led by the general Kim Yu-sin whilst Tang emperor Gaozong sent a navy of 130,000 men, which sailed up the Geum River. With such an overwhelming force Baekje was caught in a pincer movement, the capital Sabi crushed and the kingdom wholly swept aside in 660 CE. Silla then easily quashed a brief rebel revival in 663 CE; one kingdom down, one to go.

Once again the Tangs were instrumental in Korean affairs when Pyongyang, the Goguryeo capital, was attacked by a Chinese army in 661 and again in 667 CE. The city, after a one-year siege, eventually fell, and by 668 CE the Goguryeo kingdom was made a Chinese province as was now the old Baekje territory. Silla had no intention of allowing China to keep these gains, though, and while the Tangs were preoccupied with a rising Tibet, the Silla armies battled the Chinese forces remaining in Korea. Battles at Maesosong (675 CE) and Kibolpo (676 CE) brought victory, and finally, Silla was the sole master of Korea.

Government & Social Classes

As in the other states of the period, below the royal court a central government controlled the kingdom with officials appointed to oversee the six provinces (pu). The Silla kings may have had less power than their counterparts in other kingdoms, though, as they shared government with a small council of aristocrats, the hwabaek, which decided on even the most important issues of state such as declarations of war.

The Silla kingdom was unusual in that amongst the long line of male sovereigns two Queens ruled – Seondeok (r. 632-647 CE) and Jindeok (r. c. 647-654 CE). The former gained the throne because her father, king Jinpyeong (r. 579-632 CE) had no male heir. Her reign was distinguished by the increased integration of Buddhism as the state religion. Jindeok followed in her cousin's footsteps and helped Silla dominate the Korean peninsula. There would be a third queen – Jinseong (r. 887-898 CE), who ruled in the Unified Silla Period.

The majority of the king or queen's subjects were farmers who worked their own land but who were also required to provide labour for government projects such as the construction of fortifications and, in time of war, to fight in the Silla army. An aristocracy dominated administrative and religious positions with their wealth coming from trade and landed estates worked by slaves (largely drawn from prisoners of war and criminals). Aristocratic youths were trained in the Hwarang or 'Flower Boys' system, which, despite its Buddhist teachings, emphasised martial prowess and heroism.

In 520 CE, king Beophung introduced the bone rank system (Golpum or Kolpum). This was a classification of social ranks based on birth, which permitted holders of a certain status to apply for specific levels of jobs within the government administration and determined how much tax they would pay. There were originally three levels: 'sacred bone' (seonggol), 'true bone' (jingol), and 'head rank' (tupum). The latter was the largest and further divided into six levels. The bone rank system was all-pervasive and even dictated such seemingly trivial matters as what types of clothes one could wear, the size of one's house, and the means of transport one was permitted to use. The system was extremely rigid with next to no movement possible between levels, a fact which may have accounted for the social stagnation of the Silla kingdom which eventually contributed to its downfall.

Relations with China

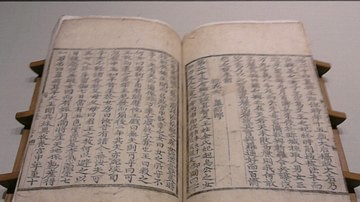

In the 4th century CE, Silla maintained diplomatic relations with China, paying regular tribute to the regional powerhouse. From the 6th century CE Silla rulers adopted the Chinese title wang (king) – which replaced the maripkan or 'elevation' title of previous Silla kings, the Chinese writing system, Confucianism during the Han period, and Buddhism, which became the official state religion in 535 CE, even if traditional shamanistic practices continued too. When Taoism became more popular during the Tang period, so too it became more widespread in the Silla kingdom.

The two states were long-time trading partners with China exporting silk, tea, books, and silver goods while Silla sent in return gold, horses, ginseng, hides, ornamental manufactured goods such as tables, and slaves. The reigns of Queen Seondeok and king Taejong Muyol in the mid-7th century CE saw an even closer relationship with Tang China with Tang court customs followed at Kumsong, students sent to China for study, and most significantly of all, massive military aid being sent to help Silla quash their rival kingdoms.

Silla Art

The most celebrated works of Silla craftsmen are, undoubtedly, the gold and gilt-bronze crowns excavated from several royal tombs, which justify the capital being named Geumseong or 'city of gold'. Made of sheet-gold and decorated with granulation and crescent-shaped pendants of jade (magatama), they have tall upright antlers and trees, which indicate a link with shamanism. There are not only crowns, though, but jewellery, belts, shoes, girdles, and cups made of thin sheet-gold, intricately carved, and embellished with gold wiring, granulation, long pendants, and pieces of jade.

Stone and gilt-bronze sculptures were produced, especially of the Buddha, bodhisattvas, and the future Buddha, Maitreya. A gilt-bronze statue of the latter type from c. 600 CE is one of the outstanding pieces of ancient Korean sculpture. The statue presents a contemplative figure with a delicately poised hand, crossed leg and flowing robe; it is currently on display in the National Museum of Korea, Seoul.

Silla pottery of the Three Kingdoms period was mostly grey stoneware with incised, applied, and pierced decoration. Two forms predominate: the long-necked jar (changgyong ho) and round, lidded cup with a wide foot base known as kobae (but used for food, not liquids). Other shapes include horned cups, cups with wheels attached, one-handled cups, large bulbous jars, lamps, and bell cups which have small pieces of clay inside a hollow lower section so that they rattle when lifted. Pottery stands (kurut pachim), used to support large bowls, were also made which have intricate pierced designs. Perhaps the most impressive pottery objects are the ewers in the form of armoured horse-riders.

Silla Architecture

Typical Silla tombs of the Three Kingdoms period are composed of a wooden chamber set in an earth pit which was then covered with a large pile of stones and a mound of earth. To make the tomb waterproof, layers of clay were applied between the stones. Many tombs contain multiple burials, sometimes as many as ten individuals. The lack of an entrance has meant that many more Silla tombs have survived intact in respect to the other two kingdoms and so provided treasures from golden crowns to jade jewellery. The largest such tomb, actually composed of two mounds and containing a king and queen, is the Hwangnam Taechong tomb. Dating to the 5-7th century CE, the tomb measures 80 x 120 m, and its mounds are 22 and 23 m high.

Notable surviving structures at Gyeongju include the mid-7th century CE Cheomseongdae observatory. Nine metres tall, it acted like a sundial but also has a south-facing window which captures the sun's rays on the interior floor on each equinox. It is the oldest surviving observatory in East Asia.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.