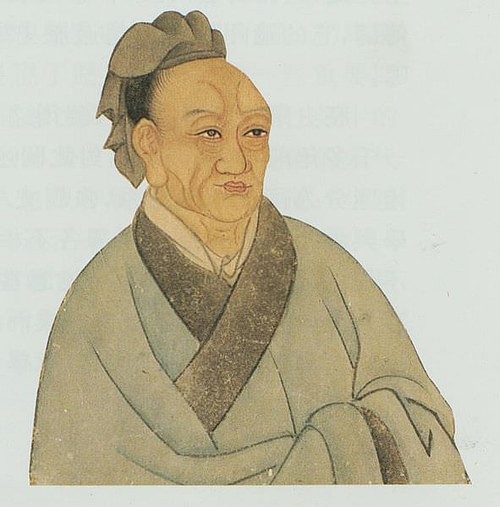

Sima Qian (l. 145/135-86 BCE) was a court scribe, astrologer, and historian of the Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE) of ancient China, famous for his historical work Records of the Grand Historian for which he is remembered as the Father of Chinese History.

He lived and wrote during the reign of the emperor Wu Ti (also given as Wu, Wu Di, and Wu the Great, r. 141-87 BCE). He was the son of Sima Tan (l. c. 165-110 BCE), who had also been court astrologer and historian. The term 'historian' at this time did not have the same meaning it does today. A court historian in China at this time was expected to immortalize his emperor's reign and dynasty, often including elements of myth and fable. Sima Tan conceived of a new use for history – recording and preserving the past of the entire nation factually – and inspired this same vision in his son.

Sima Tan started work on what he saw as a great project but only completed a small part of it before he died. Sima Qian took up his father's work and finished the monumental work Records of the Grand Historian c. 94 BCE, enduring great personal suffering to do so. Records of the Grand Historian changed the way history in China was written as well as how it was understood.

It originally existed in two copies – one in the imperial archives and the other in Sima Qian's house – and sections of it may have been published shortly after it was completed. The house copy was published, presumably in full, by Sima Qian's grandson, Yang Yun, during the reign of Emperor Xuan (74-48 BCE) who encouraged literacy and the arts.

It is unclear how the work was initially received but it was known and used by the historians Ban Biao (l. 3-54 CE) and his son Ban Gu (l. 32-92 CE) in their work Hanshu (the Book of Han). Any later work of Chinese history has followed this same paradigm in drawing on Sima Qian's work as the model for historical writing. The Records established Sima Qian's reputation, posthumously, as the preeminent historian of China, just as he knew it would, and even with modernist criticism, the work and its author continue to be admired.

Early Life & Troubles

Sima Qian was born in either 145 or 135 BCE in the Shaanxi Province to well-off, but not upper-class, family. His father was the court astrologer who held the title “grand historian” but whose primary function was divination based on observation of the yearly calendar and writing accounts of the emperor's deeds, court life, and affairs of state. Sima was devoted to his father and acquired his same interests in scholarship. He was no doubt well-educated and most likely pursued his intellectual interests outside of class.

At what point Sima Tan first told his son of the grand project is unclear. According to Sima Qian's own account, it was only when his father was dying that he was asked to complete the work. It could have been earlier, however, because, in 126 BCE, he embarked on a tour of historical sites throughout China which could have simply been encouraged by his own interests or could have been in preparation for joining his father on writing the history. He is said to have visited many sites of historical and cultural significance, including Confucius' hometown of Qufu in the state of Lu where, as a Confucian, Sima Qian reports being moved deeply upon seeing the master's personal items and clothing still preserved.

He had returned home, married, and had at least one daughter (and possibly two sons), by c. 122 BCE when he accepted a position as attendant to Emperor Wu Ti. This position also involved travel as he followed the emperor to various parts of the realm on inspections and in performing rituals. Sima Qian was called home in 110 BCE when his father fell ill and was not expected to recover. Sima Qian claims, as noted, that it was at this point, as his father lay dying, that he was asked to complete the histories.

Sima Qian continued in his position as attendant for three years before he was promoted to his father's old post c. 107 BCE. He seems to have lived a comfortable life, working on the Records in his spare time, and was clearly valued by the emperor who, in 104 BCE, appointed him to the committee on reforming the calendar, a position of honor. He is also said to have composed poetry, prose works, and rhapsodies during this time and later of which only one has survived.

He continued in the emperor's good graces until 99 BCE when he made the mistake of defending a friend, the general Li Ling (d. 74 BCE), against the charge of treason. Li Ling had been sent north to fight the Xiongnu, the fierce tribe who lived beyond the border of the Great Wall, along with the emperor Wu Ti's brother-in-law Li Guangli (d. 88 BCE), but not together; each general had their own front to face. Li Guangli was defeated on his front and Li Ling was also but on a much larger scale, losing most of his men and surrendering.

Emperor Wu Ti condemned Li Ling as a traitor because Li had promised him a resounding victory, had refused practical measures such as reinforcements to protect a supply line, and had wound up not only disappointing the emperor and losing almost 5,000 soldiers in battle but also surrendering and allowing himself to be taken prisoner. When Sima Qian defended Li Ling, the emperor took it as an insult to Li Guangli, who was also defeated but not referenced in Sima Qian's defense of Li Ling, and an insult to himself that a court astrologer should contradict the Chinese emperor's decree.

Emperor Wu ordered Sima Qian arrested and sentenced to death unless he could pay a large fine to have the sentence commuted. Sima did not have the money and so had to choose between execution or castration and three years in prison. The honorable decision, according to the understanding of the time, would have been death, which would have saved face and maintained his family's social standing, but Sima chose castration and imprisonment because he had not yet completed the Records.

He chose humiliation, dishonor, castration, and three years in prison in order to finish the work because he believed in its importance. He had noted, in his travels and his reading of the histories, that those who tried to do good often led painful and difficult lives and were thought of poorly while those who clearly did whatever they wanted and indulged every self-interest at other people's expense lived well. He understood that written history could reward the good, and punish the evil, by providing an account of their lives and deeds which would last as long as people could read.

Further, the stories of the past dynasties, of the philosophers and statesmen, of the common people of the farms and fields, might be manipulated by someone else who wrote their histories instead of being treated impartially and factually as he had been doing thus far. He decided to live, even though he would have to suffer, and this decision changed how history would be understood and written ever afterwards in China.

Histories Before the Records

In order to understand the importance of Sima Qian's work, one must understand the progression of history up until the time he wrote and what constituted “history”. The Han Dynasty succeeded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) which had emerged triumphant from the era of chaos known as the Warring States Period (c. 481-221 BCE) and the earlier Spring and Autumn Period (c. 772-476 BCE) which saw the steady decline of the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE). The Zhou had succeeded the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046) BCE which were the first to develop a system of writing.

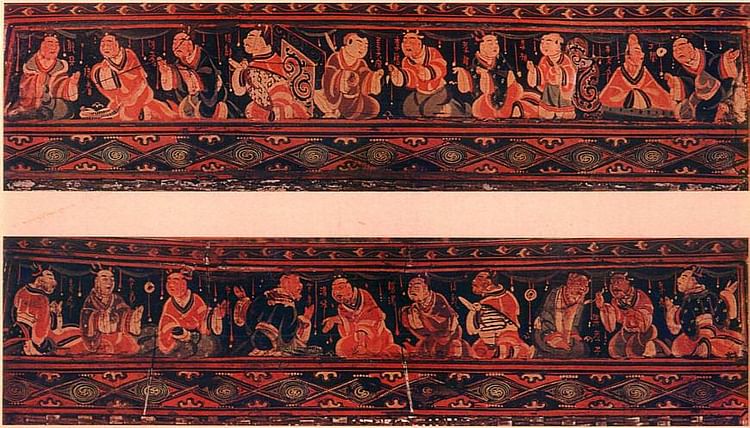

Prior to Sima Qian's work, histories were restricted to the story of the dynasty, the ruling house, the monarch, or the state. During the Shang Dynasty, evidence of these types of accounts was found on oracle bones; during the Zhou, they were written and bound as bamboo books.

The foundational works of Chinese culture are known as The Four Books and Five Classics:

- The Book of Rites

- The Doctrine of the Mean

- The Analects of Confucius

- The Works of Mencius

- The I-Ching

- The Classics of Poetry

- The Classics of Rites

- The Classics of History

- The Spring and Autumn Annals

During the Han Dynasty, all of these were believed to have been either written or edited by Confucius based on the claims made by the Confucian scholar Mencius (Mang-Tze, l. 372-289 BCE). Modern-day scholars largely reject Confucius' role in most of these works (except, of course, those clearly attributed to him), but this is a very recent shift in interpretation; the claim Confucius authored or edited all these works was accepted until the 20th century CE.

Many if not all of these works were informed by the era known as the Hundred Schools of Thought (or Contention of the Hundred Schools of Thought) of the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period when the decline of the Zhou Dynasty encouraged scholars and philosophers, previously working for the state, to found their own schools of thought, either officially or unofficially.

The designation Hundred Schools of Thought should be understood figuratively to mean there were many which contended with each other for adherents and acceptance. There were fourteen which later writers (Sima Qian among them) considered important enough to remember and these were:

- Confucianism

- Taoism

- Legalism

- Mohism

- School of Names

- Yin-Yang School

- School of Minor Talks

- School of Diplomacy

- Agriculturalism

- Syncretism

- Yangism (Hedonism)

- Relativism

- School of the Military

- School of Medicine

The Qin Dynasty based its policies on Legalism and condemned all these other schools, ordering their books to be burned and their advocates executed. Confucian and other works only survived, for the most part, because people hid them from authorities at considerable risk to their lives and those of their families. Prior to the Qin's censorship, though, most of these schools had already been either stamped out or absorbed by the three which would go on to inform Chinese culture – Confucianism, Taoism, and Legalism – and the central concept of one school, the School of Names, was adopted by Confucianism.

The School of Names (also known as the School of Logicians or as The Logicians) was founded by the logician scholars Hui Shih (l. c. 380- c. 305 BCE) and Kung-sun Lung (b. c. 380 BCE) whose focus was the correlation between words and the objects/concepts they represented. Their school of thought concentrated on an examination of how closely the word for “desk” – as an example – correlated to an actual desk. This encouraged precision in the use of language which would become an important aspect of Confucian thought.

Sima Qian, a Confucian, drew upon the Four Books and Five Classics, which had been revived by the Han Dynasty, in his work and paid particular attention to the Spring and Autumn Annals which were said to have been composed by Confucius with special attention to the very concept developed by the School of Names: how well a word represented the reality it was supposed to convey. Accordingly, Sima Qian composed his work as precisely as possible in an attempt to express the realities of the stories he was telling as accurately as he could.

Records of the Grand Historian

The result of his efforts was his masterpiece, the Records of the Grand Historian which differed significantly from the “histories” of the past. Scholar Raymond Dawson comments:

In talking about the Chinese historical tradition, one has to be very careful to qualify this term. The development of a distinct body of literature separately recognized as history was only a very gradual process. The pre-Qin writings which we categorize as history consisted of works that had a very different aim from that of the modern historian. In remote antiquity, rulers needed to have in their entourage people who could place on record and preserve oracular responses concerning important state events and people who were expert at elucidating the links between natural phenomena and human events. (xxix)

Dawson is here describing the responsibilities of the position Sima Tan (and later Sima Qian) held which was the same as court “historians” before him: observing the calendar and various events and making a – hopefully – auspicious prediction for the emperor's coming year as well as recording what he did and other events of his reign. Sima Qian's work, as noted, differs significantly from earlier so-called historical works in providing a relatively objective account of the history of China from the time of the legendary Yellow Emperor (c. 2712-2599 BCE) to the time of his writing.

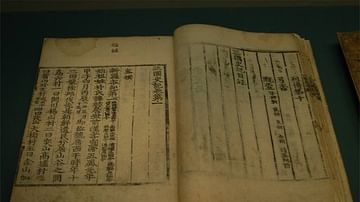

The Records is composed of 130 chapters which were originally written on bamboo slips of approximately 30 characters per slip which were then bound into thirty slips per bundle. In time, the work was reproduced on silk and finally, in the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), on paper. The work is divided into five sections:

- Basic Annals – chronicles of the past dynasties of Xia, Shang, Zhou, and Qin up through the Han to Sima Qian's time

- Chronological Tables – genealogies of ruling houses and chronology of reigns as well as major events

- Treatises – on the development of important cultural advances such as music, rituals, the calendar and divination, matters of state, other matters of interest

- Hereditary Houses – ruling houses of the Shang through Han dynasties

- Biographies – stories of individuals most often written to convey some moral or culturally relevant point.

The Records of the Grand Historian is not only a more thorough treatment of the past than what was conceived of before, however, but is considered, overall, far more accurate. In addition to drawing on the written sources mentioned, Sima Qian also interviewed older people for first-hand accounts, visited famous (and not so famous) historical sites and spoke with people there, and seems to also have had access to other sources now lost. His attention to precision in language creates detailed images and characterizations which, coupled with his mastery of narrative form, produced a work of history which reads with the progression, and sometimes suspense, of a novel.

Conclusion

Sima Qian made one handwritten copy of the Records which was deposited in the imperial library at Chang'an and kept the original at his home. After his death, the work was kept safe by his daughter, Sima Ying, who feared it would be destroyed by the emperor Zhao (r. 87-74 BCE). It was first published by her son, Yang Yun, in the reign of Emperor Xuan who was more tolerant and encouraged the arts and literary expression. It was already in use as a reference work, as noted, during the Han Dynasty and continued to find an audience following the turbulence of the Period of the Three Kingdoms (220-280 CE) which succeeded the Han and on through the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) by which time it had become a foundational classic of Chinese literature almost on par with the Four Books and Five Classics. Its reputation has only grown since and it continues to attract an audience in the present day. Dawson comments on the unique character of the work:

What makes it particularly remarkable to the modern eye is the complexity of its construction. It is not a mere narrative history [but a detailed account of the past in five cohesive sections]. The whole massive work, of 130 chapters, is meant to contain a history of the Chinese world from the beginning down to about 100 BCE, the time when it was being written. (xxi)

Writing the Records of the Grand Historian must have seemed a daunting task at first as nothing like it had ever been attempted before. Some modern-day scholars have suggested that Sima Qian simply copied earlier histories or paraphrased events in his own words, but this is what historians do on a regular basis and have for centuries. What makes Sima Qian's work significant is that it was entirely unique in Chinese history when it was published. Earlier “historians” had only needed to record the deeds and past of the royal house they served; Sima Qian extended the scope of history to the distant past.

It is easy to criticize the work now that Sima Qian's techniques have become standard, but such criticism says far more about critical scholars than the work itself. Sima Qian endured the humiliation of imprisonment, castration, and loss of social rank because he knew that the work he was engaged in was more important than his personal comfort or the transient concept of honor. He valued the preservation of his country's past above any personal considerations and, in so doing, established his legacy as the Father of Chinese history.