Sir Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Baron Fairfax of Cameron (1612-1671), was the first and highly successful commander of the Parliamentarian New Model Army during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). Fairfax's leadership, tactical prowess, and courage were all evident in many battles, but his greatest triumph was utterly defeating the Royalists at the Battle of Naseby in June 1645.

Early Career

Thomas Fairfax was born in Denton, North Yorkshire on 17 January 1612, his father being the military commander Ferdinando Fairfax, 2nd Baron Fairfax of Cameron. Thomas was educated at the University of Cambridge, and he gained military experience in the Netherlands fighting against the Spanish from 1629 to 1631. He then returned home and became a cavalry commander for his father's Northern Army. In this capacity, he fought for Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) in Scotland during the Bishops' Wars (1639-1640). His king was highly satisfied with his performance, and so he was knighted in 1641. Sir Thomas became the 3rd Baron Fairfax when his father died in 1648.

The First Years of the Civil War

When king Charles wrangled with Parliament over money and religious reforms, a civil war broke out in 1641. Fairfax sided with the Parliamentarians and continued to command his cavalry within the Northern army. Successes of 1643 included the capture of Leeds and Wakefield, but under the command of his father Lord Fairfax, the Parliamentarians suffered a defeat at the Battle of Adwalton Moor in Yorkshire in June of the same year. The victory, masterminded by William Cavendish, Earl of Newcastle (d. 1676), was a serious blow to the Parliamentarian cause in the north of England, but their fortunes improved with victory at Winceby in Lincolnshire in October. The next summer, Fairfax was involved in a crucial battle, again in Yorkshire, that would decide the future of the region.

Marston Moor

Fairfax led a cavalry unit at the Battle of Marston Moor near York on 2 July 1644. It was one of the largest battles of the war and likely involved over 45,000 men. The Royalists were commanded by Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria (l. 1619-1682), Charles' nephew, and he rashly decided to attack three Parliamentarian armies withdrawing from the failed siege of York, which had ended the day before. The three armies combined outnumbered Rupert's force; they were commanded by Edward Montagu, Earl of Manchester (1602-1671), Alexander Leslie, Earl of Leven (d. 1661), and Fairfax.

The Parliamentarians surprised the enemy by attacking them late in the day when they had made camp for the night, thinking that the battle would be fought on the next day. The Parliamentarian cavalry left wing led by Oliver Cromwell and Sir David Leslie performed brilliantly and routed the Royalist cavalry. Fairfax had less success with his cavalry on the right wing against Lord George Goring's horse. Cromwell's cavalry first aided the Parliamentarian infantry to get the better of the opposition in the centre of the battlefield, and then he assisted Fairfax's cavalry. The Royalists suffered a heavy defeat, and York surrendered two weeks later so that Parliament could now claim almost total control of the north of England. Fairfax continued his campaigning, but during the siege of Helmsley Castle in Yorkshire in September, he was badly wounded in the face and forever after carried a large scar along his left jaw.

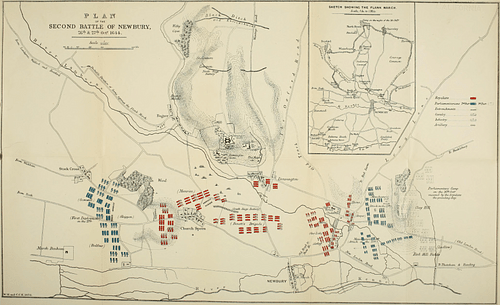

The Debacle at Newbury

Fairfax's military career was going well, but it really took off following the indecisive Second Battle of Newbury on 27 October 1644. Despite the Parliamentarians enjoying a 2:1 numerical superiority over the Royalist army led in person by Charles, they could not press their advantage, and the king retreated to fight another day. The Parliamentarian command had been slow and indecisive. Three rival commanders, all of whom refused to fully cooperate with the other two, resulted in a distinct lack of purpose on the battlefield. The guilty trio was Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex (1591-1646), the Earl of Manchester, and Sir William Waller (1597-1668).

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) and like-minded Parliamentarians longed for a much more vigorous prosecution of the war. They also wanted a more professional approach both to command and the formation and training of armies. In December 1644, Cromwell made his views clear in Parliament. In February, it was decided to replace the old system of mixed armies drawn from various counties to form, instead, a professional standing army: the New Model Army. To ensure the army was not let down by its commanders, Parliament passed the Self-Denying Ordinance, a motion which forbade any of its members from also being a military commander. This removed any commanders who were politically powerful but had no military competence. Waller, Essex, and Manchester were all casualties.

A new overall commander was needed. On 21 February, Fairfax had got the job and an impressive title to go with it: Lord General of Parliament's Forces. His second-in-command was Oliver Cromwell. Despite Fairfax himself insisting that the M.P. Cromwell be exempted from the Self-Denying Ordinance, there were some who thought Fairfax was merely Cromwell's puppet, notably the army preacher Richard Baxter who, whatever the validity of his claim, inadvertently gives an interesting character resumé of Fairfax:

This man was chosen because they [Cromwell and his Puritan fixer in Parliament Henry Vane] supposed to find him a man of no quickness of parts, of no elocution, of no suspicious plotting wit, and therefore one that Cromwell could make use of at his pleasure. And he was acceptable to sober men, because he was religious, faithful, valiant and of a grave, sober, resolved disposition, very fit for execution and neither too great nor too cunning to be commanded by the Parliament.

(Hunt, 153).

Certainly, as future events would show, Fairfax was a man of courage, integrity and principle.

The New Model Army

Fairfax could call upon 24 regiments of the New Model Army as well as smaller additional forces from elsewhere. The Commander-in-Chief was assisted by the Lieutenant-General of the Horse, the Sergeant-Major-General of the Foot, and the Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance, who commanded respectively the cavalry, infantry, and artillery regiments. Below these was a not inconsequential body of staff officers. The army had good training, leadership, and funding, and a strict disciplinary code. This last point may have had only some effect on the battlefield, but it had a definite effect on the local populations through which the Model Army marched and billeted. This was a crucial factor in a civil war where looting, pillaging and worse had become an all-too-common point of suffering for ordinary folk. Fairfax was himself a disciplinarian, once marching his entire army past two hanged offenders to get his message across.

The Model Army proved itself in emphatic style at the Battle of Naseby in Northamptonshire in June 1645. The Royalists, numerically inferior, were destroyed by the well-trained and well-disciplined Parliamentarian cavalry, especially those regiments under Cromwell. The king's dreadful loss of infantry and cavalry was a catastrophic blow to his hopes of reversing the tide of the war.

The Fall of Bristol & Final Victory

In July 1645, Fairfax faced and defeated an army led by Lord Goring near Langport in Somerset. The Parliamentary army had an advantage of 10,000 v. 7,000 men, and Fairfax made it count. Next, Fairfax set his sights on Bristol, a vital Royalist stronghold and second only to London as England's most important port. The siege of Bristol in 1645 began in September with Fairfax encircling the city and capturing several of its outer defences. The commander of the Royalists was Prince Rupert, and he refused Fairfax's demand for a bloodless surrender unless the Parliamentarians agreed to not stationing a garrison in the city in the future. This demand was not accepted, and on 10 September, Fairfax gave the order to his 8,000 assault troops to attack the city. Under the onslaught, Rupert was obliged to surrender on the 11th, in the event, a sensible decision given the weight of numbers against him. However, being allowed to leave the city and rejoin King Charles, his monarch nevertheless remained wholly unimpressed and definitively dismissed Rupert from the royal army.

The New Model Army gained yet more victories at the Battle of Rowton Moor in Cheshire in September 1645, the Siege of Chester from September 1645 to February 1646, and at the Battle of Torrington in Devon, also in February. The last Royalist army defeat came at the Battle of Stow-on-the-Wold in Gloucestershire on 21 March 1646. Fairfax had clearly been an excellent choice.

The Second Civil War

The First English Civil War (1642-1646) was over, but King Charles, now in Scotland, refused to give up. With promises to promote the Presbyterian Church in England, he persuaded a Scottish army to invade in what became known as the Second English Civil War (Feb-Aug 1648). Fairfax commanded the Parliamentarian troops in Kent and Essex, where English rebels had once more taken up arms. At the Battle of Maidstone in June 1648, Fairfax defeated a Royalist army led by the Earl of Norwich. Fairfax then attacked a defiant Royalist force near Colchester and, after they retreated into the city, besieged it. General Fairfax reduced the suburbs to rubble, cut off the water supply, and refused to allow any civilians to leave, not even women and children. After enduring atrocious conditions within and reduced to eating horse meat, the city surrendered on 28 August. The army looted Colchester while Fairfax rounded up the Royalist leaders and had them shot. Meanwhile, Oliver Cromwell defeated a combined Royalist and Scottish army at the Battle of Preston in Lancashire in the same month.

The Parliamentarians had won the Second Civil War, but as long as King Charles was alive, there remained the burning question of what to do with him. Some wanted a reduced monarchy, others to scrap the institution altogether, others even to execute Charles. Some Parliamentarians wanted to disband the New Model Army now that it had served its purpose, but it marched on London in December 1648 against such a measure and to receive the back pay it was due. Fairfax supported the claims of his soldiers, but he did not condone their attacks on Parliament. Sir Thomas favoured a constitutional monarchy and did not agree with the extremists, but, in the end, they won the political battle. Charles was put on trial (which Fairfax refused to attend), found guilty of treason, and executed on 30 January 1649. The country became a republic with the title and office of the monarchy abolished (but not in Scotland). The House of Lords was also abolished, and the Anglican Church was reformed. A ruling Council of State took over as head of the government, which included 41 members, one of which was Fairfax. Scotland remained loyal to the crown, and Charles I's eldest son Charles was, by right of birth, made its king.

Distancing from Cromwell

Charles II then persuaded the Scots to invade England in a second restoration attempt, just as they had with his father two years before. Fairfax refused to lead the Parliamentarian army against Scotland. Not only did he not agree with the regicide but he had, after all, recently inherited his family title, a Scottish peerage. General Fairfax resigned his command, and so from 1650, the New Model Army was led by Cromwell. He first ruthlessly quashed a Royalist rebellion in Ireland and then won a great victory at the Battle of Dunbar in Scotland in September 1650. With the capture of Edinburgh and more victories, the so-called Third English Civil War (1650-1651) was over.

In December 1653, Cromwell was appointed head of the new republic, the Lord Protector of England. Fairfax retired from public life, although he made a brief return when he supported George Monck (1608-1670) and the Restoration of the monarchy in May 1660 when Charles II of Scotland also became Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685). Fairfax's absence from politics in the intervening decade and his support of the Restoration ensured that he escaped the unpleasant acts of vengeance that other prominent Parliamentarians suffered as the monarchy reasserted itself.

Thomas Fairfax died on 12 November 1671 in his native Yorkshire. He had served as one of the most effective commanders during one of England's most troubled periods of history. As Cromwell noted in a letter to Parliament:

The general served you with all faithfulness and honour; and the best commendation I can give him is that I dare say he attributes all to God and would rather perish than to assume to himself, which is an honest thriving way, and yet so much for bravery may be given to him in this action as to a man.

(Wanklyn, 166)