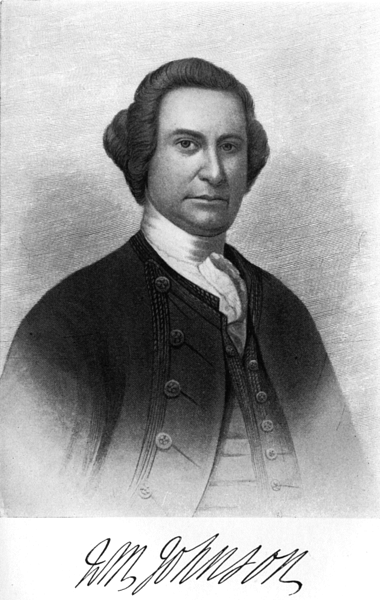

Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet (l. c.1715-1774) was a British military officer, diplomat, and Superintendent of Indian Affairs. He was instrumental in aligning the Native Americans of New York with the British during the French and Indian War and served as a Major-General with distinction.

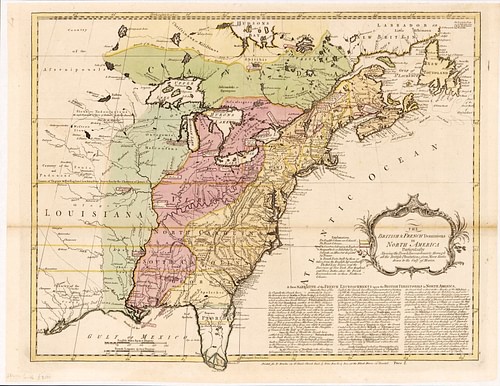

After first emigrating to the Mohawk River Valley from Ireland in 1738, Johnson quickly formed ties with the Iroquois Confederacy, immersing himself in their language and culture. As the British and French Empires clashed over the dominance of North America, Johnson was tasked with winning the neutral Iroquois over to the British cause, invoking the old Anglo-Iroquois diplomatic relationship known as the Covenant Chain. He was eventually successful and led Iroquois warriors to battle in key engagements during the French and Indian War, helping to turn the tide of the war in favor of the British and to bring French control of Canada to an end.

Early Life & the Beaver Trade

William Johnson was born in County Meath, Ireland, c. 1715. His parents were both Catholics; his mother, Anne Warren, came from the English gentry whose status was denigrated by their Catholicism, whilst William's father, Christopher Johnson, was an Irishman whose family had been involved in Jacobitism, the movement that supported the restoration of the Catholic Stuarts to the British throne. These factors greatly limited the ambitious William's prospects in the British Isles, and so, when his uncle, Admiral Sir Peter Warren, offered him the opportunity to tend his 14,000-acre farm in the Mohawk Valley in the colony of New York, 22-year-old William jumped at the chance.

Johnson arrived at his uncle's land in 1738, with twelve Irish Protestant families to start clearing the land. Shortly thereafter, whilst running an errand at the British outpost of Fort Hunter, he encountered the Mohawks, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. Upon learning that Johnson oversaw his uncle's store, the Iroquois complained to him about the difficulty of having to travel all the way to Oswego on Lake Ontario whenever they wished to trade with the British. Johnson saw profit, and by 1739, he had set up his own trade post in Oquaga, deep within Iroquois territory, where he involved himself in the fur trade. A shrewd businessman, he charged the Iroquois half of what the Oswego traders did. As a result, he made enough money in the next two years to buy his own plot of land, which he called Fort Johnson.

Along with his newfound riches, Johnson also found himself becoming increasingly involved in Mohawk culture. He learned their language, something most other traders and diplomats never attempted due to its difficulty, and he met with Mohawks in their own villages. Johnson soon caught the eye of Hendrick Theyanoguin (l. c. 1691-1755), a Mohawk chieftain who needed someone to help him navigate the world of English politics. Hendrick met with Johnson, and the two parted as friends, with the Mohawks adopting Johnson as one of their own, bestowing upon him the name of "Warraghiyagey" ("he who undertakes great things").

Colonel of the Six Nations & the Covenant Chain

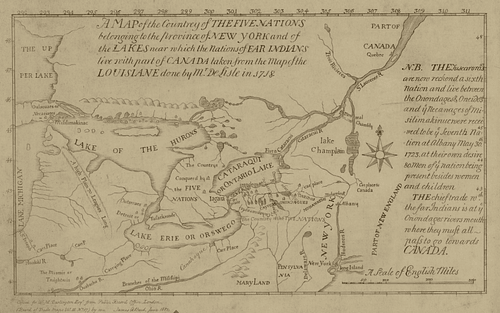

After his adoption, Johnson became the spokesman for Iroquois interests in Albany. His close relations with the Iroquois, especially the Mohawks, also interested the British, who were concerned that the Iroquois would side with the French the next time the two colonial empires clashed. There had been a history of cooperation between the British and the Iroquois, dating back to when the English first took control of the colony of New York from the Dutch in the mid-17th century. It could be argued that this relationship, known as the Covenant Chain, was borne more out of necessity than any feelings of friendship, as the Iroquois had grown reliant on the trade of European goods, including guns needed in their constant conflicts with the French-backed Algonquins.

This was the political landscape William Johnson stepped into in 1746 when he was appointed Colonel of the Six Nations, his task being to revive the Covenant Chain to prepare the Six Nations to do battle against the French at the outbreak of King George's War (1744-1748). This would be a harder task than it would seem. Unsurprisingly, many Iroquois distrusted the British, with some even preferring an alliance with the French. With French Jesuits at work in the upper Seneca and Onondaga nations, these nations began to spearhead the Francophile faction within the Iroquois Confederacy, with the Onondagas going so far as to allow the French to build the strong Fort Niagara within their territory.

The Mohawks remained the most Anglophile of the Six Nations, and when Johnson summoned Iroquois warriors to Fort Johnson to prepare for war, it was mostly Mohawk warriors who arrived, at the urging of his friend Chief Hendrick. Johnson sent raiding parties against French settlements, paying bounties for scalps, but he was never able to mount a larger campaign during the war, even after being given command of the colonial militias at Albany. By the time news of peace reached the Americas in July 1748, many Mohawks under Johnson's command had died from a smallpox outbreak or as casualties in the raiding parties. Facing so much destruction and death while never actually seeing the great empires do much damage to one another, some Iroquois came to the belief that the wars between Britain and France were lies, nothing but a conspiracy by the colonial powers to lessen Iroquois influence, destroy the Confederacy, and kill its people.

Mending the Chain: the French & Indian War

As Johnson was attempting to repair his reputation with the Iroquois in the early 1750s, the French and Indian War (1754-1763) was ramping up. In 1755, as part of a concerted campaign against the French, Johnson was given the rank of major general and instructed to capture the French fort at Crown Point, west of Lake Champlain. Alongside a contingent of 1500 colonial troops, Johnson and Chief Hendrick were able to muster a band of 200 Mohawks to aid in the campaign. By 8 September, Johnson's ragtag army had made it to the southern end of Lake George, where they engaged a superior army of French regulars and native allies.

The Battle of Lake George resulted in one of the first British victories of the war, a breath of fresh air in a campaign season that was otherwise filled with defeats. The French commander, Baron Dieskau, was captured and Johnson was hailed as a hero, receiving a baronetcy for his actions. However, this victory came at a cost: Johnson himself was wounded in the hip, and his friend and ally, Chief Hendrick, was killed.

Although the battle was hardly a decisive one, it did underscore to Johnson the value of having native allies, especially when up against a foe who relied on them; one of the key aspects that led to Johnson's victory was the reluctance of France's allies to join the battle, for fear of killing their Mohawk kinsmen. When the Mohawks went home after the battle, explaining they had a custom of returning home after a conflict where they sustained any significant loss, Johnson knew he had to repair the Covenant Chain in full.

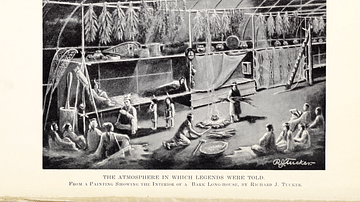

In 1756, Johnson was made Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the north, a powerful position that allowed him to bypass colonial authority by reporting directly to London. As superintendent, Johnson focused mostly on the goal of repairing British relations with the Iroquois as well as officially drawing them into the war. Over the next three years, he would spend many months over council fires with the Iroquois, trading wampum belts and trying to convince the sachems of the sincerity of British intentions. Records of most of these meetings can be found in the Documents Relative to the Colonial History of New York.

On 3 June, Johnson attended the first of these fires at Onondaga, where the Six Nations convened, accompanied by a contingent of Mohawks to remind the Iroquois that he was one of them. Around the fire, he passed two belts of wampum, the first meant as a gesture of friendship on behalf of the British, the second serving as an appeal to "dispel the dark clouds so that they may see the Sun clearly", a metaphorical plea for the Iroquois to make the right choice of ally (Brodhead, Vol. 7, 134). After Johnson's belts had been passed around, the gathered sachems explained that they had previously been given white belts of friendship by the Governor of New France, who asked the Iroquois to "come speedily to Montreal" in order to discuss matters that would be "for the welfare of the Six Nations." (Brodhead, 137). The French sent the belts with a warning that the Iroquois would be bringing about their own ruin should they allow the English to encroach on their lands.

Many Iroquois sachems had reason to take the French offer seriously; the memory of the destruction seen during King William's War (1688-1697) was still fresh, and many remembered how the English had done nothing but "sit still and smoked [their] pipes" while Iroquois people were being killed (Broadhead, 263). The Iroquois, especially the French-leaning Upper Nations, did not want to fight the French without assurance that the British would not abandon them, explaining that they no longer had a sufficient warrior population to defend themselves alone.

Johnson responded with a warning that the Iroquois be wary of trusting the "crafty and insidious" French. He shamed the leaders of the Upper Nations for considering taking up the Canadian governor's invitation, reminding them that they would be disgracing their ancestors by siding with the French, who had so long been their enemies, imploring them not to meet again with such a "deceitful and perfidious Nation" (Broadhead, 140). To ease their fears, Johnson promised that forts would be constructed within Iroquoia, which would be garrisoned by British soldiers if the Iroquois could not supply enough of their own men. Johnson told them that this would be done even at great expense to "the King, your Father." To assuage fears that the British were indeed encroaching on their lands, Johnson promised that the forts would be "destroyed or given up as soon as the difference between [the British] and the French is decided" (Broadhead, 148).

The council of 1756 seemed to appeal to the Mohawks, Oneidas, and Tuscarora, who were already leaning Anglophile. However, the Seneca, Onondaga, and Cayuga Upper Nations were less convinced, especially after Fort Oswego fell to the French in August. These nations restated their desire to remain neutral. At a meeting at Fort Johnson in 1757, Johnson called this "base and foolish conduct," reminding them again of the Covenant Chain, and the mutual agreement of protection that went with it. "Have not the French hurt us?" Johnson asked. "Are they not daily killing us and taking our people away?" He asked them to respect the vows of their ancestors, saying, "Brethren, our end of the chain is bright and strong…but it seems to me that your end is grown very rusty, and without great care, is in danger of being eaten thro'" (Broadhead, 261).

The next year, 1758, Johnson had a chance to see where his hard work negotiating had gotten him. British General James Abercrombie was planning an attack on Fort Carillon and ordered Johnson to gather all the warriors he could and join the attack. Johnson summoned all six nations to Fort Johnson, where he issued one final call to arms:

Brethren, This is the day of Trial, and I shall now see what Indians are my Friends, for such will go with me…remember, Brethren, we were successful Together 3 years ago & I hope I shall now lead you to conquest and Glory. (Flick, 938).

Johnson ended his speech with a war dance, and sachems from all six nations joined him. Gathering 450 Iroquois warriors, Johnson marched to take part in Abercrombie's massive expedition.

The Battle of Fort Carillon ended up being a disaster for the British, but Johnson found his luck with the Iroquois changing. The construction of Fort Stanwix within Iroquois territory seemed to confirm to them the protection he had been promising all along. The witnessing of the attack on Fort Carillon, although a British defeat, did go to convince some of the more cynical Iroquois that the British were indeed committed to fighting the French, and battles elsewhere that year convinced them that a British victory was possible. Finally, the issue of trade also convinced many sachems to trust the British, simply for the fact that they had no choice. Because of the war, trade with Canada was becoming increasingly difficult, leaving the Iroquois, who at this point depended on European goods, no choice but to deal with the British.

These factors resulted in the Six Nations finally throwing their support behind Johnson and the British. In 1759, Johnson led 1,000 Iroquois warriors as part of the expedition to capture Fort Niagara. This was nearly the entirety of Six Nations' fighting strength, as well as the largest native American force assembled under a British flag. When the British commanding general was killed, Johnson took command of the entire expedition and captured the fort. This was a great victory for the British, as it not only drove the French from the Great Lakes Region but also deprived France of its ability to supply its forts and outposts in the Ohio River Valley, effectively cutting French colonial possessions in two. More than that, it was a personal victory for Johnson, who finally united the Six Nations behind their old friendship with the English.

Later Years & Legacy

After his stunning victory at Fort Niagara, Johnson took part in the capture of Montreal in 1760, using his talents to negotiate with the former allies of the French. Upon returning home, he was given 80,000 acres of land by the Mohawks, making him one of the largest landowners in the British colonies with a combined land holding of 170,000 acres. It was on this land that he built the town of Johnstown and constructed Johnson Hall. He remained involved in Native American affairs, helping to negotiate an end to Pontiac's War in 1766, as well as the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, which confirmed the boundary between Native American lands and lands belonging to the thirteen colonies.

By 1759, Johnson, who was notorious for his affairs that resulted in numerous illegitimate children, entered a common-law relationship with Molly Brant, a Mohawk woman who was the older sister of future Mohawk leader Joseph Brant. She lived with him for the rest of his life at Johnson Hall, and the couple had eight children together, further strengthening his Mohawk ties.

On 11 July 1774, Johnson suffered a stroke and died the same day. During the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), his properties were seized by the government of New York due to his family being loyalists. Johnson's legacy is the peaceful co-existence that persisted for a time between the British and Iroquois worlds. A British subject by birth and a Mohawk by adoption, the Mohawk Baronet did his best to restore the faith between his two peoples, while also helping to deal a decisive blow to French ambitions in America.