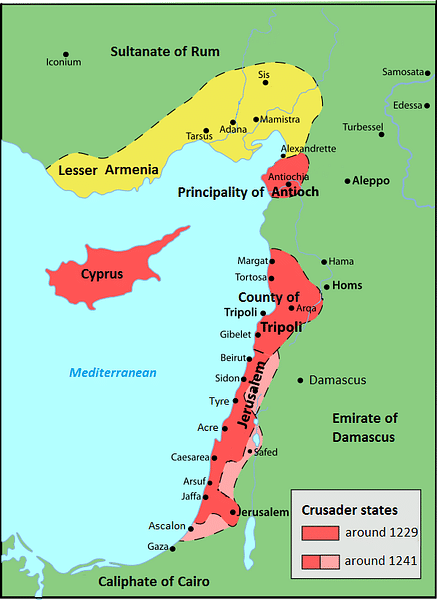

The Sixth Crusade (1228-1229 CE), which for many historians was merely the delayed final chapter of the unsuccessful Fifth Crusade (1217-1221 CE), finally saw the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (r. 1220-1250 CE) arrive with his army in the Holy Land, as he had long vowed to do. Jerusalem had been out of Christian hands since 1187 CE but was finally won back from Muslim control thanks to Frederick's skills at diplomacy rather than any actual fighting. In February 1229 CE a treaty was agreed with the Sultan of Egypt and Syria, al-Kamil (r. 1218-1238 CE), to hand over the Holy City to Christian rule. Thus, the Sixth Crusade managed to achieve by peaceful means what four bloody previous Crusades had failed to do.

Prologue: The Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade was called by Pope Innocent III (r. 1198-1216 CE) in 1215 CE. Capturing Jerusalem for Christendom was again the objective but the method this time changed to attacking what was seen as the weaker underbelly of the Ayyubid dynasty (1174-1250 CE): Egypt rather than the Holy City directly. The Crusader army, although eventually conquering Damietta on the Nile in November 1219 CE, was beset by leadership squabbles and a lack of sufficient men, equipment and suitable ships to deal with the local geography. Consequently, the westerners were defeated by an army led by al-Kamil, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria, on the banks of the Nile in August 1221 CE. The Crusaders, forced to give up Damietta, returned home, once again with very little to show for their efforts. There were bitter recriminations afterwards, especially against Frederick II Hohenstaufen, king of Germany and Sicily, for not turning up to the show at all when his army could well have tipped the balance in the favour of the Crusaders. One consequence of the Fifth Crusade was that the decision by the west to attack Egypt did highlight to the Ayyubids their own vulnerability in the southern Mediterranean.

Frederick II

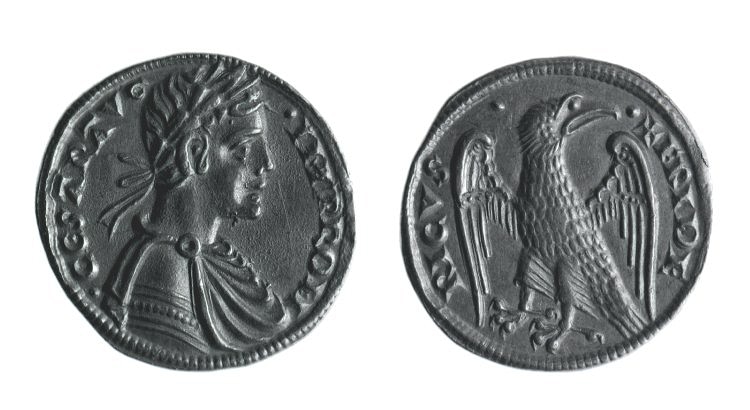

Although Frederick II had done nothing in the Fifth Crusade except overshadow it by his absence, he would eventually become one of the great figures of the Middle Ages, as the historian T. Asbridge here colourfully summarises:

In the thirteenth century he was lauded by supporters as stupor mundi (the wonder of the world), but condemned by his enemies as 'the beast of the apocalypse'; today historians continue to debate whether he was a tyrannical despot or a visionary genius, the first practitioner of Renaissance kingship. A paunchy, balding figure with bad eyesight, physically Frederick was rather unprepossessing. But by the 1220s, he was the Christian world's most powerful ruler. (563)

At the time of the Sixth Crusade, then, Frederick was still negotiating the early rocky patches of his long road to greatness. Frederick had not left Europe during the Fifth Crusade, despite his promise to do so, because he had found himself in a power struggle with the Papacy over his right to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor. First Pope Innocent III, and then his successor Honorius III (r. 1216-1227 CE), had been concerned at Frederick's control of both central Europe and Sicily, effectively encircling the Papal States in Italy. Honorius pushed for Frederick to fulfill his original crusader vows and take back Jerusalem for Christendom; the distraction might also prove advantageous to the Papacy and allow them some breathing space in Italy.

Frederick was finally made Holy Roman Emperor in 1220 CE and he acquired a more personal connection to the Middle East when, in November 1225 CE, he married Isabella II, the heiress to the throne of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The emperor would, after all, travel to the Levant and take the Kingdom of Jerusalem, throne and all, for himself. Assembling a large Crusader army, Frederick's departure, long-since scheduled for 15 August 1227 CE, was delayed once again, this time by illness (possibly cholera). The new pope, Gregory IX (r. 1227-1241 CE) ran out of patience and excommunicated the dithering would-be Crusader in September 1227 CE as the papacy had earlier vowed to do if the emperor's promises were not honoured. It was not a good start to the Crusade. Still, those leaders of the Crusade who had already made it to the Middle East took the opportunity of the delay to put their men to good use and get on with some building work, refortifying such key strongpoints as Jaffa, Caesarea, and even a brand new headquarters castle for the Teutonic Knights at Montfort.

Frederick in the Levant

Despite his problems with the Church, Frederick II was undeterred and arrived in Acre in the Middle East on 7 September 1228 CE determined to do what so many nobles before him had failed to do: take Jerusalem. He certainly had the best trained and equipped men of any previous Crusader army, almost all his warriors being paid professionals and numbering some 10,000 infantry and perhaps 2,000 knights. There remained the inconvenience of Frederick's excommunication and this had the practical result that some of the leaders of the pious military orders in the Levant, especially amongst the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller, felt that they could not be seen to be serving a figure outside the Church. The emperor got around this problem by appointing separate and (theoretically) independent commanders for these knights to follow.

The emperor's plans had also been slightly knocked out of tilt with the tragic death of Isabella during childbirth in May 1228 CE. Frederick decided to reign as regent for his newborn son Conrad, replacing his father-in-law John of Brienne, who had been regent for his daughter Isabella prior to her marriage. John, who had led the army of the failed Fifth Crusade, was not best pleased to be ousted from power and swore revenge. Frederick was not without other opposition in the kingdom of Jerusalem where many nobles resisted any changes to the political status quo. Frederick's plans to redistribute certain hereditary lands and his promotion of the Teutonic Knights military order were particular sticking points.

Jerusalem: A Negotiated Peace

Frederick and his army marched from Acre to Jaffa in early 1229 CE to pose the threat such a force had promised to do ever since the Fifth Crusade. At the same time, al-Kamil faced a dangerous coalition of rivals within the Ayyubid dynasty. In the last two years, the Sultan's own brother, al-Mu'azzam, the emir of Damascus, had joined forces with fierce Turkish mercenaries, the Khwarizmians, to threaten al-Kamil's territory in northern Iraq. Al-Mu'azzam died of dysentery in 1227 CE but the threat from his followers, especially to al-Kamil's ambitions in Damascus, which was now led by al-Kamil's rebel nephew al-Nasir Dawud, remained. Consequently, the two leaders began negotiations to avoid a war which would seriously damage both side's commercial interests in the region.

Frederick was, no doubt, helped in his diplomatic efforts by his knowledge of Arabic and a general sympathy towards the culture, the emperor having his own personal corp of Muslim bodyguards and a harem - products of his time in Sicily with its significant Arab population. Al-Kamil, on the other hand, had already offered Jerusalem as a bargaining chip during negotiations with the Fifth Crusaders and, if need be, he could always retake Jerusalem once this Crusader army had departed back to Europe. It seems that both leaders were keen to safeguard their own empires and their much more important assets elsewhere than squabble over Jerusalem. At the same time, any gains could be maximised and the concessions minimised when presenting the deal to each leader's followers.

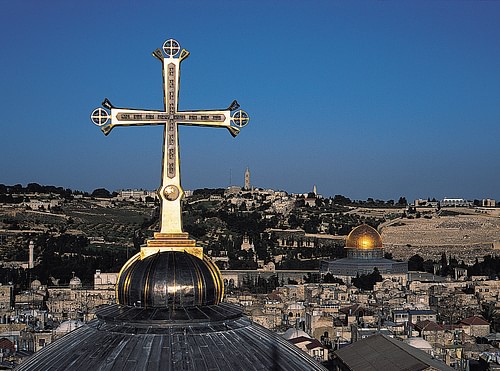

On 18 February 1229 CE the Treaty of Jaffa was signed between the two leaders which permitted Christians to reoccupy the holy places of Jerusalem, except the Temple area which remained under the control of the Muslim religious authorities. Resident Muslims were to leave the city but could visit the holy sites on pilgrimage. Under the detailed terms of the agreement, no new construction or even artistic additions were permitted at those holy sites. Neither could any fortifications be built (although it would later be disputed that this applied to Jerusalem). Included in the deal were other important sites of great significance to Christians such as Bethlehem and Nazareth. The Sultan, in return for these concessions, got a 10-year truce guarantee and the promise that Frederick would defend al-Kamil's interests against all enemies, even Christians.

Frederick then entered Jerusalem in triumph on 17 March 1229 CE and crowned himself in an impromptu ceremony in the Holy Sepulchre. However, the local nobles were aggrieved at not having been consulted during the negotiation process and the commoners were not very appreciative of this foreign monarch meddling in their affairs either. A group of disgruntled Latins in Acre even pelted the emperor with meat and offal as he left for home in May 1229 CE. Frederick was sorely needed back in Italy where Pope Gregory IX had cynically taken the opportunity of the emperor's absence to invade southern Italy with Sicily the ultimate target. Significantly, the leader of the pope's army was Frederick's own father-in-law, John of Brienne.

Aftermath

Jerusalem would remain in Christian hands until 1244 CE, although throughout Acre remained the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. With the emperor gone and his two nominated regents unpopular, the Latin nobles continued, as before, with their damaging rivalry for control of the Crusader states. Meanwhile, al-Kamil received criticism for his peace deal from Muslims far and wide, even from amongst the Ayyubid princes, but he did finally take control of Damascus. The Muslim control of the Middle East was greatly strengthened when a large Latin army was defeated at the battle of La Forbie in October 1244 CE. These events resulted in the Seventh Crusade (1248-1254 CE) and the Eight Crusade (1270 CE) which continued the strategy of attacking Muslim-held cities in North Africa and Egypt. Both campaigns were led by no less a figure than the French King Louis IX (r. 1226-1270 CE) but neither were very successful, even if Louis was later made a saint for his efforts.