Sleipnir is the eight-legged horse ridden primarily by the god Odin in Norse mythology. He is the son of the god Loki (in the form of a mare) and the stallion Svadilfari who belonged to the jötunn that built the walls of Asgard. In Iceland, the glacial canyon Ásbyrgi is known as Sleipnir’s Footprint in the horse’s honor.

According to legend, the great horse, carrying Odin, rode through this area and one of his hooves landed amidst a forest, creating the canyon. This story is typical of tales concerning Sleipnir, which often depict him as immensely large, carrying Odin through the realms where some evidence of their passage is left behind. In other stories, he seems only slightly bigger than an average horse, only with eight legs.

Sleipnir is always depicted as incredibly swift and the "best of all horses", symbolized by his eight legs that carry a rider anywhere in the nine realms of Norse cosmology in record time. Since he was born of two supernatural entities, he is possessed of the power to move easily between realms, including the realm of the dead, leading to his name (pronounced Slayp-near), which means "the sliding one".

Although he is almost always ridden by Odin, in the story of the death of the god Baldr, he is ridden to the realm of Hel in the afterlife by Baldr’s brother Hermóðr. Sleipnir is able to easily jump the high fence around Hel and then bring Hermóðr safely back to the gods at Asgard. The great horse also features in the tale of Odin’s race with the giant Hrungnir who is killed by Thor when he threatens the Asgardians.

Sleipnir’s final ride is to carry Odin to the battlefield of Vigrid at Ragnarök, the Twilight of the Gods. In the final battle between the forces of chaos that include Loki and Sleipnir’s half-siblings Fenrir, Jörmungandr, and Hel – among others – on the side of chaos, most of the Norse gods are killed, including Odin and his faithful horse. Sleipnir is then thought to carry Odin to the afterlife in keeping with the traditional understanding of the horse a liminal being in Norse mythology.

Horses in Norse Belief

In Scandinavian culture, the stallion replaced the bull as the symbol of virility and power, but horses generally were understood as possessing supernatural abilities that placed them in communion with the gods and spirits. There was no clergy in Norse religious practice, but there was the figure of the völva (seeress), a woman who received messages from the gods, could predict the future, and presided over community rituals. The völva was highly respected, but it was recognized that horses were closer to the gods and could understand them better than any völva. Scholar H. R. Ellis Davidson comments:

The horse was an animal which could be associated with the journeying sun and it was an important religious symbol in the North from the Bronze Age onwards. A horse could carry a departed hero to the realm of the dead and is shown doing this on many of the memorial stones set up in Gotland in the Viking Age. Like Freyr’s boar, Odin’s horse traveled swiftly though the sky and down into the realm of death. In the first century AD, the sacred horses of the Germans were held to understand the will of the gods more clearly than their priests could do, according to Tacitus, so that they were used for divination. (53)

The divination took the form of harnessing a horse, or horses, to a chariot or wagon and then observing the path they took, usually between spears or other projectiles set on the ground in front of them. Although there are no stories of Sleipnir predicting the future overtly, he is thought to be quite intuitive, knowing the fastest way to reach a destination to minimize risks to his rider.

Sleipnir’s Eight Legs

Sleipnir is first mentioned by name in 10th-century Eddic poetry which was among the sources used by the Icelandic historian and mythographer Snorri Sturluson (l. 1179-1241) for the Prose Edda, a unified narrative of Norse myths written in the 13th century. The eight-legged horse as a shamanic symbol of transformation, however, predates Sleipnir’s name (at least in writing) as Gotland rune stones feature the image of Odin on the eight-legged horse arriving in the afterlife as early as the 8th century.

Sleipnir’s famous eight legs have been claimed by some modern-day writers to be a result of his magical birth which left him deformed, but scholars reject this claim noting that they were probably imagined to convey the concept of speed. Scholar Rudolf Simek, for example, points out that, "on the Gotland stones, the eight legs merely serve to give the impression of speed and the pictorial tradition paved the way for the eight-legged horse in literary tradition" (293-294). Simek also claims that the story of Sleipnir’s magical birth is most likely an invention of Sturluson who added his own imaginative touches to many of the Norse myths.

It has also been suggested that the eight legs symbolize cosmic balance and transformation, as well as suggesting stability, and while this may be true, the original intent seems simply to suggest speed. Sleipnir is later known as the ancestor of the great hero Sigurd’s horse, Grani, also known for his speed and referred to as "the best of horses", so speed was clearly central to the horse’s attributes.

Magical Birth

Sleipnir is also mentioned in the various works that make up the Poetic Edda, notably Baldrs Draumar (“Baldur’s Dreams”) when Odin rides him to the realm of Hel to ask the spirit of a witch what his son’s dreams portend. His origin story comes from the Prose Edda in the tale of the construction of the walls of Asgard and Valhalla.

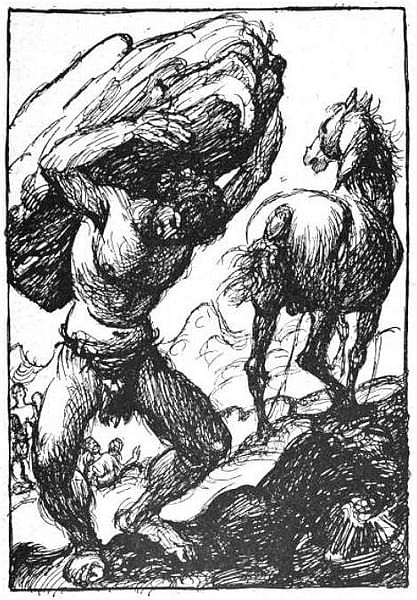

After the gods had created and ordered the Nine Realms, they set about building a protective wall around their home of Asgard and the Hall of Heroes, Valhalla. While they are discussing how best to go about this, an unnamed man appears and offers to do it for them in exchange for the goddess Freyja, the sun, and the moon. The gods are not eager to accept the proposal, but Loki, the trickster god, talks them into it. The gods place stipulations on the agreement, however, that the master-builder must complete the walls in three seasons (spring, summer, fall) and must do so without the help of any other man. The builder asks if he can use his horse, Svadilfari, to help, and, again after Loki’s influence on the discussion, the gods agree.

It quickly becomes apparent to them that Svadilfari is no ordinary horse as he can move stones from great distances faster than any man could. With his horse’s help, the builder has almost completed the walls days before the deadline. The gods are not interested in paying what he asked and turn on Loki as the one responsible for the agreement. They tell him that he must fix this or face the worst death they can devise for him.

Loki transforms himself into a beautiful mare and, that night, trots out to where Svadilfari is moving stones. The stallion is instantly attracted to the mare and runs toward her, but Loki-as-mare bolts away into the woods. The builder runs after Svadilfari, chasing him all night, and so the wall is not completed by the deadline. The gods discover that the builder is a jötunn – a denizen of the realm of Jotunheim, land of the frost giants – who are enemies (or at least on uneasy terms) with the gods of Asgard. They call on Thor to take care of this problem for them, and he appears, smashes the builder’s skull with his hammer, and that ends the difficulty the gods’ faced of the builder perhaps objecting to non-payment. Loki-as-mare, meanwhile, has been finally brought to ground by Svadilfari and impregnated, later giving birth to Sleipnir.

Odin’s Race

Odin took Sleipnir as his own, as chief of the gods, and rode him throughout the Nine Realms on his various journeys. One day, he rides in Jotunheim and encounters the giant Hrungnir who admires Sleipnir. Odin boasts that his horse is the best to be found anywhere, and Hrungnir is annoyed, claiming that his own horse, Gullfaxi ("Golden Mane") is better and faster.

Odin challenges Hrungnir to a race, and the two set off galloping on their horses toward Asgard. The Asgardians have no interest in allowing a jötunn inside their walls, but Gullfaxi is so swift that he is right on Sleipnir’s tail and Odin wins by only a hairsbreadth. Feeling he must offer hospitality, he offers Hrungnir a drink, which the giant quickly drains and then calls for more.

Hrungnir becomes drunk and begins threatening the Asgardians. He roars that he will kill them all, destroy Asgard, and take Odin’s Hall back to Jotunheim as a prize along with the beautiful goddesses Freyja and Sif, Thor’s wife. Hrungnir has already (at some point) kidnapped Thor’s daughter Thrud (later returned or, perhaps, escaped) and so he is hardly well-regarded even before he begins his drunken rant. The gods call for Thor who challenges Hrungnir to a duel and smashes his skull with his hammer just as he did with the builder of the walls of Asgard.

The giant falls and his leg lays across Thor’s throat. None of the Asgardians are strong enough to lift it except Thor’s three-year-old son Magni who rescues his father. As a reward, Thor gives Magni Gullfaxi so that now the two greatest horses in the Nine Realms both reside in Asgard.

Death of Baldr

Sleipnir is also featured in one of the most famous pieces from North mythology, the tale of the death of Baldr. Baldr was the son of Odin and his wife Frigg and was considered the most beautiful, the kindest, and wisest of the gods. In the poem Baldrs Draumar from the Poetic Edda, Baldr begins having nightmares of some impending doom. Odin mounts Sleipnir and travels to Hel, the realm of the dead, to find out what the dreams mean.

Hel is surrounded by a high wall to keep the dead in and the living out, but Sleipnir is able to easily travel between realms and so brings Odin directly inside. There he notices that Hel has been cleaned and swept, the floor covered in gold, the benches newly laden with fresh hay for seating. He summons the spirit of a völva (given as “witch” in some translations) and asks her what this means. She tells him that Hel has been prepared to welcome the soul of Baldr who is shortly to arrive.

The poem ends with the völva telling Odin to return to Asgard as he will be in Hel himself soon enough after Ragnarök, but the tale is continued in the Prose Edda in Section 49 of the Gylfaginning where Frigg, upset at the prospect of losing her son, goes throughout the Nine Realms extracting a promise from all things animate and inanimate that they will not harm Baldr.

Baldr is universally loved and so the promises are given easily. Afterwards, the gods of Asgard take up the sport of hurling objects at Baldr to watch them bounce harmlessly off in accordance with their pledge. Loki watches this game one day and, deciding to cause trouble, transforms himself into a woman and goes to visit Frigg in her palace at Fensalir.

Frigg asks what the Asgardians are up to, and the woman tells her that they are at their usual sport of lobbing all kinds of things at Baldr. She then asks the queen if it is really true that all things in the Nine Realms took the oath to protect him, and Frigg innocently replies that she never asked the mistletoe because it was so young and harmless. Loki instantly leaves, finds some mistletoe to the west of Valhalla, and brings it to Asgard where he sees Baldr’s blind brother Hodr standing to the side of the festivities, feeling sad because he cannot participate. Loki tells him he will guide his aim and Hodr flings the mistletoe which pierces Baldr, killing him instantly.

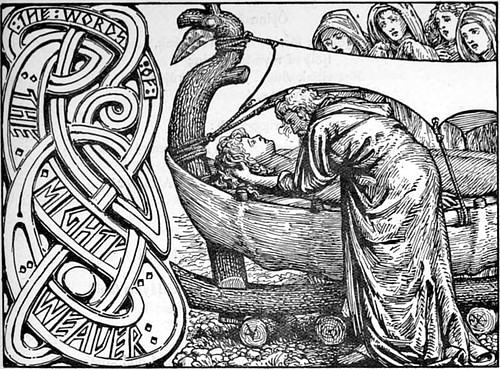

The gods are devastated by his death and Frigg appears, weeping over her son, and asks someone to ride to Hel and ask for Baldr’s return. Hermodr, Baldr’s brother, volunteers, and Odin saddles Sleipnir for him. Hermodr rides for nine nights down the descending road to Hel, crosses the bridge above the river of spears, and is told he cannot enter because he is a living being. Sleipnir easily jumps the walls of Hel, however, and Hermodr finds Baldr’s spirit being entertained grandly in a great hall in the presence of Hel, Queen of the Dead, and Baldr’s wife Nanna, who has died of grief since Hermodr left Asgard.

Hermodr makes his request, and Hel agrees to return Baldr and Nanna if all the Nine Realms shall weep for him. Hermodr rides Sleipnir out of death’s realm and back to Asgard, and all the realms do weep for Baldr except for the giantess Thokk (who is actually Loki in another form), who claims the dead belong with the dead. Baldr must remain in Hel’s realm until the end of the present world at Ragnarök.

Ragnarök

Ragnarök had been foretold by the Norns – the Fates whose visions could not be altered – and was the end of the Nine Realms and many of those who lived in them. It was the final great battle between the forces of chaos and those of order and would be heralded by Sleipnir’s half-brother, Fenrir, the great wolf. First would come a breakdown in human relationships and a failure to honor traditional customs, and then three severe winters, without summer between, would bring famine to the lands. Fenrir, bound by Odin and the Asgardians to a rock on an island, would break his chains and rampage through the realms while his son Sköll swallowed the sun and his other son Hati took the moon.

Sleipnir’s other half-brother, Jörmungandr the World Serpent, rises from the sea sending tidal waves through the realms while his half-sister, Hel, provides an army of the dead to her father Loki who brings Surtr and his fellow ire giants to the battlefield. The gods of Asgard with the fallen heroes of Valhalla face the forces of chaos in the great battle where Odin charges against Fenrir on the back of Sleipnir. The great wolf devours them both and is then killed by Odin’s son Vidarr. Most of the gods die in the battle, including Thor and Loki, but the forces of order are victorious – even as Surtr and his giants set the Nine Realms ablaze – and a new world eventually rises from the ashes.

Conclusion

Sleipnir is never depicted simply as Odin’s horse but rather as his companion who shares in adventures. His death with Odin in the last great battle echoes not only their relationship but also the way a Scandinavian or Icelandic audience would have understood horses: as liminal beings able to bridge the space between the land of the living and that of the dead.

Horses were frequently included in Norse burials as they were considered essential to one’s afterlife, but, as with dogs, they were also understood as guides who would bring the soul of the deceased safely to its destination. Lindow notes how this concept is made clear not only through excavated graves and tombs but also by the Gotland stones:

Some of the eighth-century picture stones from the island of Gotland show eight-legged horses, and most scholars accept that these represent Sleipnir. A rider sits on each, and some scholars think this is Odin; indeed, above horse and rider on the Alskog Tjangvide stone is a horizontal figure with a spear, perhaps a Valkyrie. A woman greets the rider holding a cup and the entire scene has been interpreted as the arrival of the rider in the world of the dead. (277)

Sleipnir falls in battle with Odin because he had to in order to ensure his friend reached the other realm safely. The horse was always understood to be in tune with the will of the gods and, through them, with the vibrations of the Universe, always knowing the swiftest way to any destination and always vigilant of their rider’s safety. This idealized vision of the horse is epitomized in Sleipnir who is praised as the best of all horses not only for his speed but his devotion to the one he carries.