The Song (aka Sung) dynasty ruled China from 960 to 1279 CE with the reign split into two periods: the Northern Song (960-1125 CE) and Southern Song (1125-1279 CE). The Northern Song ruled a largely united China from their capital at Kaifeng, but when the northern part of the state was invaded by the Jin state in the first quarter of the 12th century CE, the Song moved their capital south to Hangzhou. Despite the relative modernisation of China and its great economic wealth during the period, the Song court was so plagued with political factions and conservatism that the state could not withstand the challenge of the Mongol invasion and collapsed in 1279 CE, replaced by the Yuan dynasty.

Foundation

The chaos and political void caused by the collapse of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) led to the break-up of China into five dynasties and ten kingdoms, but one warlord would, as had happened so often before, rise to the challenge and collect at least some of the various states back into a resemblance of a unified China. The Song dynasty was, thus, founded by the Later Zhou general Zhao Kuangyin (927-976 CE) who was endorsed as emperor by the army in 960 CE. His reign title would be Taizu ('Grand Progenitor'). Making sure no rival general ever became too powerful and gained the necessary support to take his throne, the emperor introduced a system of rotation for army leaders and swept away all opposition. Further, he ensured that the civil service henceforth enjoyed a higher status than the army by acting as their supervisory body.

Emperor Taizu of Song was succeeded by his younger brother, Emperor Taizong ('Grand Ancestor'), who reigned from 976 to 997 CE. The stability provided by the long reigns of the first two emperors (at least compared to the chaotic previous centuries) gave the Song dynasty the start it needed to become one of the most successful in China's history.

Consolidation & Government

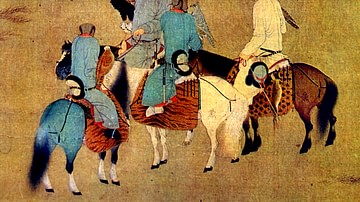

Taizu may have conquered much of central China but neither he nor his successors could manage to conquer the Khitan Liao dynasty in the north, who still controlled the vital defensive area of the Great Wall of China. Indeed, so superior were the Khitan horsemen that they invaded Song China at will and Song emperors were compelled to pay their neighbours annual tribute in the form of silver and silk. They also recognised the Khitan ruler as an emperor in his own right. A similar situation arose with the Tangut Xia state to the north-west. Following a defeat in 1044 CE tribute was paid to them, too, so that the Song emperors could maintain a peaceful border and concentrate on consolidating their rule of central China and managing their 100 million subjects. The tribute payments were huge but less than the costs of a war or maintaining a constant military presence in the region. In addition, as trade thrived between these states, much of the value of the tribute, in any case, came back to China as payment for Chinese exports.

Although the Song were able to govern over a united China after a significant period of division, their reign was beset by the problems of a new political and intellectual climate which questioned imperial authority and sought to explain where it had gone wrong in the final years of the Tang dynasty. A symptom of this new thinking was the revival of the ideals of Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism as it came to be called, which emphasised the improvement of the self within a more rational metaphysical framework. This new approach to Confucianism, with its metaphysical add-on, now allowed for a reversal of the prominence the Tang had given to Buddhism, seen by many intellectuals as a non-Chinese religion.

The clashes of political and religious ideals at court frequently led to damaging factions and exiles but the real problem, of course, was never really addressed. That was the vast inequality in wealth which had plagued China for centuries. One attempt at reform was the New Policies of the chancellor Wang Anshi (1021-1086 CE) who wanted to ease the burden of the poorer elements of society. He forwarded such reforms as substituting disruptive labour service for a tax in kind, offering low-interest loans and making new land surveys which sought to more fairly assign tax obligations. The reforms were met with almost total opposition, though, by the local administrators whose interest was the status quo and their well-established network of friends and kickbacks. The practical reality was that while more people than ever had the opportunity to join the scholar-bureaucrat class which ran the Chinese state at national and local level, and even if the lower aristocracy significantly widened its base, the vast majority of the population during the Song dynasty remained, as ever, overworked and overtaxed farmers.

Economy

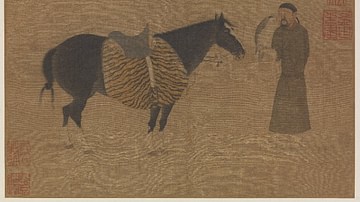

If Song politics was somewhat troublesome for the emperors, at least the economy was booming. Kaifeng, already a capital in earlier dynasties, was one of the great metropolises of the world under the Song. With a population of around one million, the city was benefiting from industrialisation and was well-supplied by nearby mines producing coal and iron. A major trade centre, Kaifeng was especially famous for its printing, paper, textile, and porcelain industries. Such goods were exported along the Silk Road and across the Indian Ocean, along with tea, silk, rice, and copper. Imports included horses, camels, sheep, cotton cloth, ivory, gems, and spices.

Farming, in general, became much more efficient, and farmers aimed at producing more than they required for their own needs. Cities became more densely populated, markets thrived, and rural farmers began to grow crops they knew would demand high prices such as sugar, oranges, cotton, silk, and tea. To transport all these goods by canals and sea to where they were in demand thousands of ships were built, and so another industry became a success story. Companies became larger and more sophisticated with different levels of management and ownership. Guilds, wholesalers, partnerships, and stock companies all developed as the Chinese economy began to slowly take on the appearance of something more akin to today's industrial model.

Arts & Science

China under the Song developed into a more modernised and industrialised nation thanks to innovations in machinery, agriculture, and manufacturing processes. Significant inventions or improvements on existing ideas included paddle-wheel ships, gunpowder, paper money, the fixed compass, the sternpost rudder, lock gates in canals, and the moveable-type printing press. Iron armour was mass-produced, and swords were made from high-quality steel made possible by water-powered bellows creating super-heated furnaces.

Literature boomed during the Song dynasty. Lie Jie wrote a famous treatise on architecture, his Yingzao fashi (1103 CE) and encyclopedias were written. Famous works of history were written such as Sima Guang's Zizhi tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror for Aid to Government) which, published in 1084 CE, covered Chinese history from 403 BCE to 959 CE. The period saw a great many works of poetry published. One of the most famous poets is Su Dongpo (1037-1101 CE) who wrote, as many of his contemporaries did, about love, loneliness, and sorrow. Women in the Song period may well have fared less well than their predecessors, and such practices as foot-binding, in particular, became more common, but one female poet of renown was Li Qingzhao who famously described her family's exile in 1127 CE and her sorrow at her husband's early death.

The visual arts in general flourished, fuelled by a rising demand from an ever-increasing wealthy middle class. Fine porcelain and theatre were all popular with the new urban elite. Landscape paintings aimed for greater realism, with one of the most famous being Travelling among Streams and Mountains, a 2x1 metre silk hanging by Fan Kuan (c. 990-1030 CE). Flower and wildlife painting, especially of birds, also became very popular with Song dynasty artists. Such was the development of an appreciation for art that many of the most celebrated artists had their works ingeniously copied, and these fakes, sometimes complete with the embossed seal of the famous artist, continue to fool antiquarians to this day.

Territorial Threats

By the early 12th century CE China's position as master of East Asia was coming under increasing threat from attacks in the north by the Liao and Xia states again. Even more dangerous were the Jurchen, tribes people in the north-eastern part of China. The ancestors of the Manchurians, they spoke the Tungusic language and had declared their own state, the Jin in 1115 CE. The Song took advantage of their territorial ambitions, and the two states joined forces to defeat the Liao. Unfortunately, despite achieving their goal, the Song were rather shown up for their own military weakness. Thus, in 1125 CE the Jin state attacked parts of northern China which even the great general Tong Guan (1054-1126 CE) could not stop. The emperor Huizong (r. 1100-1126 CE) was captured along with thousands of others and besides the loss of a huge swathe of territory, the Song were compelled to pay the Jurchen a massive ransom to avoid any more loss of life.

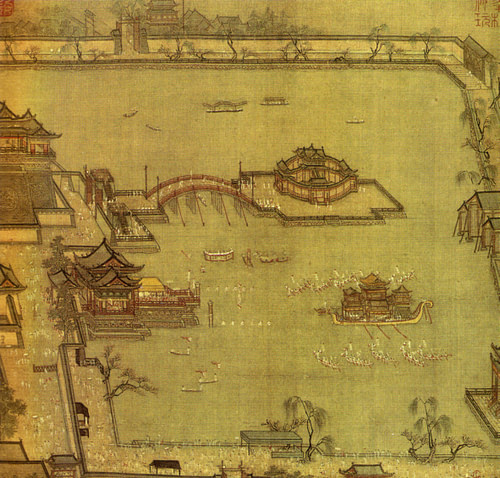

The defeat necessitated the Song court into relocating to the Yangtze Valley, and they eventually established a new capital in 1138 CE at Hangzhou (aka Linan) in Zhejiang province. This was the beginning of the Southern Song dynasty. The shrinking of the Song lands did nothing to dampen the booming economy as, fortunately, the great trading ports of the new capital, Quanzhou and Fuzhou were all in the south and continued to thrive as multinational cities where significant numbers of Muslim and Hindu immigrants took up permanent residence. The south was also much more fertile and continued to yield surpluses each harvest.

In 1127 CE the Song army made one of Huizong's surviving sons emperor, who then took the title Gaozong (r. 1127-1162 CE). After some half-hearted attempts, any plans to take back the lost lands from the Jin state were officially abandoned and a peace treaty signed in 1141 CE. Fortunately for the Song emperor, he still controlled the richest part of his former state and some 60% of the population. Hangzhou flourished. Famous for its scenic canals and gardens, it was a thriving commercial centre producing silk and ships and boasted a population of over one million. The military defeats also made the Song rulers and intellectuals rethink their strategy and make a better effort to help all levels of society. In the capital, the poor were given free handouts and medical aid, for example.

Mongol Invasion

Just when the Song had become accustomed to their new state following the tremendous upheaval caused by the Jurchen, an even greater menace appeared, and once again, it was from the north. The nomadic Mongol tribes had been assembled under the leadership of Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 CE), and they repeatedly attacked and plundered the Xia and Jin states in the first three decades of the 13th century CE. The Song thought they were next and so made ready their armies, largely funded by confiscated wealth from the landed aristocracy - a policy which did nothing for internal unity. There was to be a reprieve, though, for the Mongols were busy enough expanding their empire into western Asia.

It was not until 1268 CE that the Mongol leader Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294 CE) set his sights on the lands south of the Yangtze River. First, the strategically important city of Xiangyang was besieged, and it fell in 1273 CE thanks to the Mongol's persistence and superior catapults. The invaders crossed the Yangtze in 1275 CE and proved unstoppable. With many Song generals defecting or surrendering their armies, a court beset by infighting between the child emperor's advisors, and the ruthless slaughter of the entire city of Changzhou, the end of the Song dynasty was definitely nigh. The empress dowager and her young son Emperor Gongzong (r. 1274-5 CE) surrendered and were taken prisoner to the northern city of Beijing. Some groups of loyalists fought on for three more years, installing two more young emperors in the process (Duanzong and Dibing) but the Mongols swept all before them, setting up the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368 CE) in China, and then moved on down to Vietnam. The Song state, rich enough but paying dearly for its lack of political unity, military investment, and weapons innovation, became part of the vast Mongol empire which now covered one fifth of the globe.