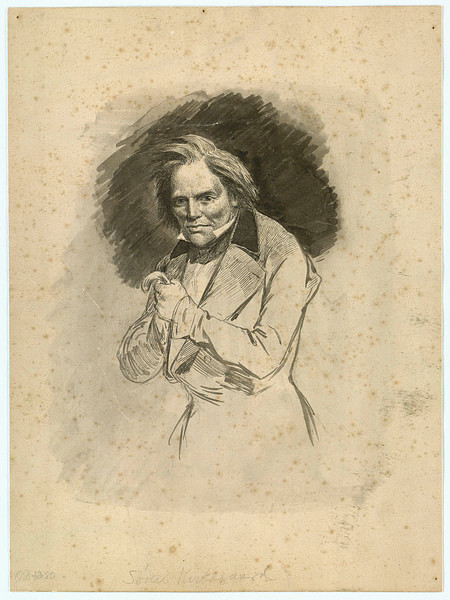

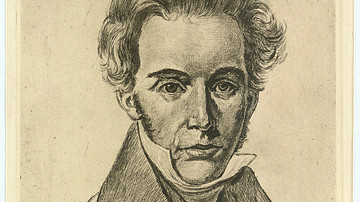

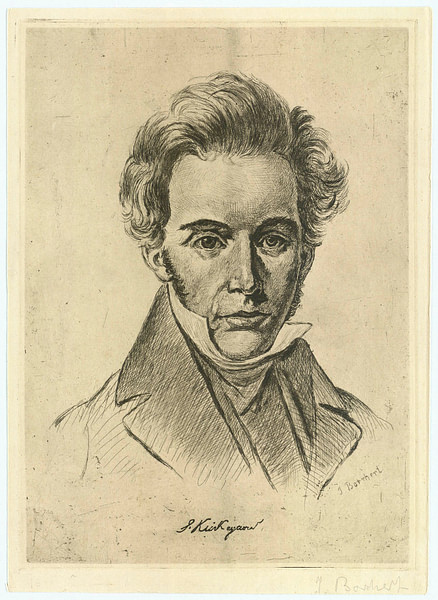

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) was a Danish philosopher and is considered to be the first existentialist, influencing such notable philosophers as Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) and Martin Heidegger (1889-1976). His works are a reflection of alienation, angst, and absurdity, and include Either/Or (1843), Fear and Trembling (1843), and The Concept of Anxiety (1844).

He was embraced by his fellow existentialists for his belief in the importance of the individual against an apathetic, hostile society. However, unlike other existentialists, his body of philosophical works has a strong theological vein. Denise Despeyroux, in her book The Philosophers, wrote that Søren's life was filled with painful experiences, which colored his works – works that displayed "great dramatic and poetic power. They are filled with parables, aphorisms, fictitious letters and diaries as well pseudonymous and fictitious characters" (110). She added that his struggles with religious questions served as a "potent stimulus" for other writers and thinkers of his generation.

Birth & Education

Søren Kierkegaard was born on 5 May 1813 in Copenhagen, Denmark, to an affluent family as the youngest of seven children. His father, Michael Kierkegaard, was a successful businessman, while his mother, Ane Sørensdatter Lund, had been the one-time maid of Michael's first wife. Søren claimed his father was the most influential figure in his life. Unfortunately, he suffered terribly from anxiety and inner turmoil, and this Søren 'inherited' from his father. Michael was deeply religious, a member of a pietistic form of Lutheranism, and was convinced that because of his past sins – he had once cursed God – none of his children would live past the age of 33, the age of Jesus Christ when he was crucified. Coincidentally, five of Søren's brothers and sisters, as well as his mother Ane, would die before Søren turned 21. Only Søren and his brother Peter survived. To Michael, it was a sign of divine retribution. According to Jeremy Stangroom in his The Great Philosophers, Søren maintained that his childhood was "insane" and "he had come into the world as the result of a crime" (100). Regrettably for Søren, his father passed on his "pessimistic and gloomy religious outlook to his son" (ibid).

Despite a chaotic childhood, his education was "surprisingly normal," attending a distinguished private school – the Borgedydskolen – where he was considered an outsider, "lonely, aloof, and intellectually the superior to his classmates" (ibid). Hoping to become a pastor as his father had suggested, at the age of 17, he entered the University of Copenhagen, where he studied theology, philosophy, and literature. In 1838, while he was attending university, his father died, leaving him with a large inheritance. After graduating in 1840, he began the life of an independent thinker and writer, but it would be a life consumed by inner torment and angst, evident throughout his writings.

Shortly after graduating, he made the mistake of getting engaged to Regine Olson, ten years his junior. He regretted the engagement the moment it was made. One year later, in 1841, he broke off the engagement, believing that his melancholic temperament made him unsuitable for marriage and he considered her to be intellectually incompatible. The affair with Regine had a lasting effect on Søren and would appear in both his journals and other works. Free from an unwanted engagement and with a large inheritance, he was free to begin a career as a writer. Oddly, throughout his life, he only left Copenhagen three times, spending most of his free time walking the streets of the city or attending the theater.

The Human Condition

Because of his journals, which he kept since turning 21, critics and proponents have had an opportunity to understand both his brief tormented life and his philosophy. Using irony, satire, and humor to make his point while writing under a pseudonym, he enabled his readers to concentrate on the message, not the messenger. Under a pseudonym, he wrote a parody of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), one of the leading philosophers of the time and the dominant philosophy espoused in Denmark. Like other philosophers of the time, Hegel attempted to make religion and the Christian faith apparent to reason. Kierkegaard argued, however, that both religion and Christian faith were outside rational understanding.

As with Hegel, Kierkegaard's philosophical views were at odds with many thinkers, both past and contemporary, on the concept of the human condition. He believed that the whole history of thought had been preoccupied with the wrong concerns. Since the time of the ancient Greeks, philosophy used reason and experience to understand and make sense of the world, but they failed to truly understand the human condition. Kierkegaard wrote: "Each age has its characteristic depravity. Ours is perhaps not pleasure or indulgence in sensuality but rather durable pantheistic contempt for individual man" (Stokes 145). He believed his age lacked passion.

Truth & Existence

Kierkegaard described what he called subjective and objective truths. An objective truth is something that is true whether a person wants to accept it or not while a subjective truth (which Kierkegaard preferred) is something that may be true for that person but not for someone else. Objective truths are created by a group and cannot be trusted "as a source of insight, wisdom, and truth" (Mannion, 126). He wanted to cut through the groupthink mentality and return to the basics, making Christianity accessible to the average Christian. He thought there should be no middleman. "Religion should be directly between the individual and God" (ibid). Kierkegaard wrote that this can only be done by living a life according to the principles of a person's faith, not just going to church on Sunday.

His book Either/Or presents two modes of existence for how a person might choose to live his life. The authentic mode is hedonistic, emphasizing the importance of immediate gratification and living in the moment. The second mode is the ethical mode, which is concerned with duty and obligation, committing a person's self to an ethical life. But there is a third choice – the religious sphere – where a person might find happiness and fulfillment.

Leap of Faith

Kierkegaard celebrated the individual over the crowd. He claimed that the beliefs of the crowd were usually the wrong ones and that being human meant making decisions and confronting the obstacles that crossed a person's path. Each choice was to be made on its own merits, free from the influence of education or social tradition, even the traditional social view of morality is subjective. A person must not sway from or be swayed from his beliefs by the challenges of what society believes. He must have the integrity to stand for what he believes. James Mannion in his Essentials of Philosophy wrote that "alienation and social ostracism are sure to result … with freedom comes fear" (125). This self-awareness and independence do not come easily, and a person has to fight against the opinions of others. Kirkegaard said that the natural response to living an intellectually independent life was what was known as angst – a German word for anxiety. He believed that the church and theology are of little help in alleviating anxiety because they are illogical and an unprovable philosophy.

Many of his contemporaries who read this assumed Kierkegaard was anti-Christian; however, he was, in fact, deeply Christian, but he deemed the church had lost its way, and he wanted to spread the true meaning of Christianity. He said that "Danish Christians were churned out by the Danish state church with the greatest possible uniformity of a factory worker" (Law 124). To Kierkegaard, most people who consider themselves to be Christian are born into their faith and only practice it by attending church on Sunday and mindlessly following church dogma. A true Christian must live according to the principles of his faith. He said Christian faith involved "making a deep, personal commitment and to accept divine authority above all else" (124). He believed "authentic Christian faith" involved making a life-transforming leap beyond what is reasonable and natural. It is a leap of faith that a person must make repeatedly.

Kierkegaard believed reason can only undermine faith, never justify it. Religious belief is a matter of faith, not reason. Philosophers such as René Descartes (1596-1650), Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274), and Saint Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109), with ontological arguments, tried to prove the existence of God, but that has nothing to do with belief in God. A person must choose to believe in God passionately. It is not an intellectual exercise.

In his Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard wrote under the pseudonym of Johannes de Silentio or John of Silence. It was about God's commandment to Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. To some critics, it condoned the killing of an innocent, but Kierkegaard realized this point and emphasized that Abraham's actions were out of love, not hate; they were a leap of faith. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) considered Abraham to be wrong, for to sacrifice an innocent child is immoral. Kierkegaard considered Abraham's faith to be an example of Judeo-Christian faith. He wrote that Abraham had demonstrated his faith when he left "the land of his fathers and became a sojourner in the land of promises. ... And there he stood, the old man, with his only hope! But he did not doubt, he did not look anxiously to the right or to the left, he did not challenge heaven with his prayers. He knew it was God Almighty who was trying him…" (Fear and Trembling, 20) Abraham had faith in something other than moral law. And like Abraham, a person must have faith in something other than the moral principles that govern society. A true Christian is one who realizes his duty is not to moral law but to a higher authority, God, "the source of moral law" (Law, 124-125).

Notable Works

Among Kierkegaard's most notable works are:

- On the Concept of Irony (1841) – a criticism of Hegel

- Either/Or (1843) – it contrasted two of the three modes of existence: aesthetic and ethical

- Repetition (1843) – it presents the third of the modes of existence: religious

- Fear and Trembling (1843), written under the name Johannes de Silentio – a discussion of the Bible's story of Abraham and his near-sacrifice of his son Isaac at the command of God

- On the Concept of Anxiety (1844) – a look at anxiety or angst

Death & Influence

Although the exact cause of his death is uncertain, Kierkegaard, the father of existentialism, died in Copenhagen on 11 November 1855 at the age of 42, possibly of tuberculosis. One contention is that his ongoing battles with the Church as well as the stress of his heavy writing schedule caused his health to suffer; he collapsed and died. Kierkegaard was constantly 'embroiled' in a controversy with the Lutheran Church in Denmark, other writers, and contemporary society. While his reputation suffered near the end of his life, he would be recognized for his influence on such notable philosophers as his fellow existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger as well as Karl Popper and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

According to Stangroom, Kierkegaard realized that his writings would not be accepted during his lifetime; most of his works were written anonymously. Only in the future would their significance be appreciated. It was not until after the First World War (1914-18) and the emergence of existentialism that he became a major intellectual figure. This was primarily due to his emphasis on the importance of an individual's freedom – he referred to his thoughts as existentials. According to Stokes, Kierkegaard searched for truth – a truth that would be true for him and one that he could live and die for. This was a theme of existentialism; this made him to be the first existentialist. At the heart of Kierkegaard's philosophy was the concept of irrationality which could be interpreted as nihilism, but nihilism rejects all religious and moral principles as it considers life meaningless. Kierkegaard, of course, was not a nihilist. He did not reject religion; he only questioned the Church in Denmark as he saw it. He never denied being Christian, only disliking the Sunday Christians.